Illustrating “A World of Dreams”— Chinese Garden Paintings

Reworking One of Chen Chun’s Garden Flowers Paintings

4.26.2022

Brief History & Introduction

After the collapse of the Han dynasty, the Chinese faced “incessant palace revolutions, peasant revolts, banditry, civil war, assassination, and regicide” [3]. To escape these events, scholars and artists found solace in tending their plants, reading books, writing poetry, or painting in their flower gardens [3]. Garden estates with pavilions, pathways, bridges, waterfalls, and streams served as a getaway from familial and social duties [3]. As one enters “the world of dreams”, they can enjoy a fleeting moment of freedom and happiness [3]. Painting the garden plants, animal life, and landscapes allowed artists to immerse themselves in this beautiful world and immortalize these scenes [3]. Royal families also employed famous artists to paint the palace gardens [6]. Shuan (rice) paper, animal hair brushes, ground ink sticks, and Chinese painting colors are traditionally used by Chinese artists to create these lively illustrations [6].

In ancient China, painting was associated with sorcery, and artists carried magical abilities [4]. There were many legends written about magical artists and they were believed up to the ninth century [4]. In one legend, a painter illustrated a portrait of a woman he loved and stuck a thorn into it because she did not reciprocate his devotion [4]. The woman got sick and did not recover until she returned his feelings and the artist removed the thorn from her portrait [4]. Paintings exhibited Chinese philosophy and various important principles [4]. For example, the contraries of Yin and Yang are illustrated by hooked lines (feminine) and straight lines (masculine)[4].

Target— Chen Chun’s Garden Flowers

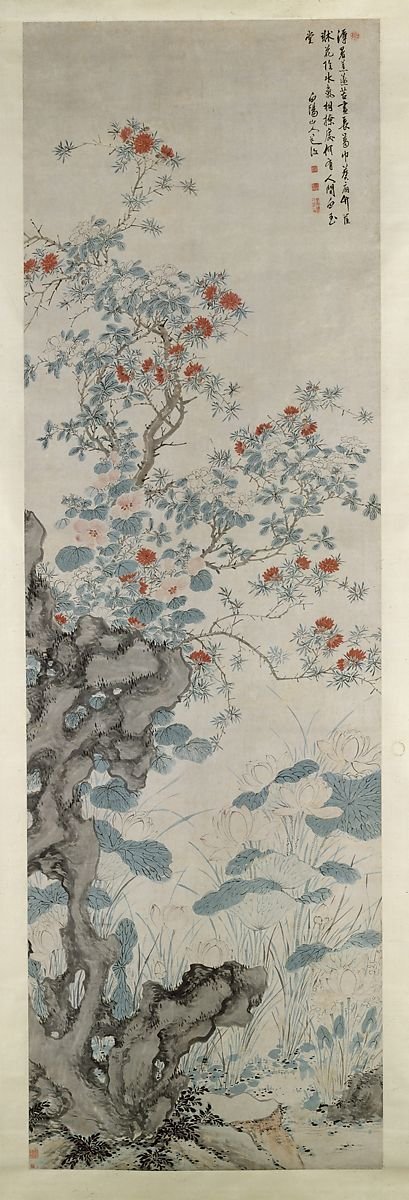

fig. 1.1: One of Chen Chun’s Garden Flowers paintings dating back to 1540 [1]. The Garden Flowers album consists of 16 floral paintings and the high-quality images of them can be found on the Met Museum website.

Source: The Met Museum

This piece was created during the Ming Dynasty period (1369-1644) [1].

Dimensions: 12 13/16 in. x 22 9/16 in. [1].

This painting shown in figure 1.1 is the target of my rework project and the primary source I examined. For this project, I sought to disprove the notion that imitating other works of art is unimaginative and requires minimal skill. I attempted to do this by replicating a Chinese garden painting created by a renowned artist (Chen Chun).

About the artist: Chen Chun (1483-1544) was a wealthy Soochow painter who created vibrant, “boneless” paintings of flowers with ink and pure colors [3]. He was the son of two notable artists (Shen Chou and Wen Cheng-ming) [3]. Unlike many other Chinese painters during his time, his work focuses on the colorful blossoms that open in the late spring & early summer [3]. His energetic and bright painting style is evident in one of his paintings titled Summer Garden, which stretches just over 10 ft high [2]. The typical plants that commonly appear in traditional Chinese paintings (lotus flowers, bamboo, plum blossoms, and chrysanthemums) are rarely seen in his paintings [3]

A potential issue with this source: The colors may not be accurate, because this is a digital image of the illustration, and it may have filters on it. There is no way of knowing what the actual colors look like without seeing the tangible painting at the Met Museum.

fig. 1.2 : This is another one of Chen Chun’s paintings titled Summer Garden.

Source: The Met Museum

Materials & Process

My Set-up & Materials—

2 sheets of handmade Shuan rice paper (190x290mm) (One for testing out the watercolors and the other for the actual painting)

Two synthetic watercolor brushes with different heads

Watercolor Palette (36 colors)

Sakura Pigma Micron Ink Pen (0.45 mm)

Cup with water (to wet paints)

Sheet of paper towel & a tissue (to dab excess paint from brushes & painting)

Other materials not in this image

Scissor & ruler (for trimming)

Phone displaying reference image

Sketchbook paper & double-sided tape

Pencil (to mark guidelines for cutting & signature)

- The colors I used for my painting are marked with a star.-

-A close-up of the brushes and the ink pen nib I used.-

Materials Used by Professional Chinese Artists—

figs. 2.1 to 2.4 : Materials used by Lian Quan Zhen (author of Chinese Water Techniques for Exquisite Flowers, award-winning artist, and painting teacher) to create professional Chinese paintings.

Source: Zhen, Lian Quan. Chinese Watercolor Techniques for Exquisite Flowers (pg 18-26)

Artist-quality materials:

In fig. 2.1 :

Chops are carved stamps used by Chinese artists to sign their names on their paintings [6].

Rouge is used to give the stamps a bright red color that contrasts with the painting [6].

A light gray fabric mat is used to provide an absorbent surface for the Shuan paper [6].

Wooden paperweights are used to keep the ends of the rice paper flat while painting [6].

In fig. 2.2:

Zhen uses only three colors for his paintings (blue, red, and yellow) to keep illustrations clean. The brands he uses include Holbein, Winsor & Newton, Da Vinci, and Van Gogh [6]. These are artist-quality paints that cost between $6-15 per tube.

In fig. 2.3:

Chinese brushes are made with animal fur. Softer brushes are created with rabbit/sheep hairs and rougher brushes are created with ox/horse hairs [6]. Zhen uses rough, synthetic sable brushes for his work [6].

Masking fluid is used to prevent contamination. It is applied to the paper and removed when the painting is finished [6]. Various tools (such as twigs) can be used to apply the masking fluid [6].

In fig. 2.4:

Wallpaper paste, paper towels, a spray bottle, and a brush can be used to smooth wrinkles from a finished piece. Another piece of Shuan paper can be attached to the back of the painting to brighten the colors [6].

—Preparation—

Detailed Preparation Steps —

I laid the paper over an image of the painting on my laptop and marked the edges with a pencil. I trimmed the rice paper into a suitable size that had dimensions that match the aspect ratio of the original piece. I created my painting on this piece of paper.

I referred to Chinese Watercolor Techniques for Exquisite Flowers on how a brush is traditionally held and adjusted my grip on the brush.

On a separate piece of paper, I tested the integrity of my watercolor paints by mixing a few colors with water and examining the consistency. Some colors had large flakes that would not dissolve in the water, so I avoided those paints by making a mark on top of them. Then I painted the usable colors onto the rice paper to see how the pigment/water reacted with the paper.

A few observations about the rice paper:

The pigment did not bleed through the paper, even though it’s fairly thin.

If I paint over the same area 3 or more times while it’s still wet, pilling occurs, and the pigment is lifted from the paper.

It is difficult to fix any errors made on this paper. If you try to scrub off the pigment, pilling occurs.

The rice paper I ordered had dried leaves woven into it. It looked lovely, but they interfered with my painting, so I picked them off carefully.

I mixed the paints and tried to match them to the original painting. In the last image of the gallery above, I tested the colors out on the scrap paper and adjusted them if needed.

It was difficult to mix the colors in large amounts because the brush held a lot of water and absorbed much of the pigment. As I painted my piece, I had to go back and mix up more of the same colors since I kept running out. By doing so, the colors appeared inconsistent in the final painting.

I observed the painting and attempted to replicate the branches, flower petals, leaves, grass, and other small details to figure out which brushes and techniques worked best for each element. The flat brush worked best for painting the branches since it created smooth edges. It also covered more space. The brush with the pointed tip worked best for the grass, petals, and all of the fine details. I found that quicker brush strokes made the grass look more natural. I used slower brush strokes to shape the flowers and leaves.

-

Breakdown of how I mixed each color:

Branches: black + periwinkle + brown + diluted with more water

Leaves: teal + dark blue + small amount of black

Pink blossoms: pink + white

Pink blossom details: red + small amount of black

Small white flower details: yellow + white

Rock: white + small amount of black

*I wish I kept a sticky note of the specific color combinations & ratios, especially since the palette contains multiple shades of each color. It has 7 shades of red, and I couldn’t remember which one I originally used. It was time-consuming to mix the paints over again and this led to inconsistent colors.

—The Painting Process—

Guide and Directions—

There are no primary sources online with instructions on how to paint Chen Chun’s illustration. Because of this, I had to rely on my own skill set and the tacit knowledge I gained from my previous painting experiences. This is a significant barrier because I am not as skilled as Chen Chun. To fill in my knowledge gaps, I referenced the tips and techniques highlighted in the secondary sources I found.

figs. 3.1 to 3.6: Visuals of the Chinese composition elements discussed by Zhen.

Source: Zhen, Lian Quan. Chinese Watercolor Techniques for Exquisite Flowers (pg 30-38)

One of the secondary sources I referenced was written by Lian Quan Zhen, who is an accomplished Chinese artist. In his book, Zhen introduces various secrets of Chinese paintings. They include the presence & location of a focal point, 7 principles of contrast, balance, 3-line integration, geometric organization, dynamic movement, and the use of white space [6]. He notes that a focal point is an essential element of a painting, and it should be located in one of the dotted circles in figure 3.1 [6]. This will establish a natural relationship between the main objects in the illustration [6]. He emphasizes how there should be contrasts between “dark and light, large and small, long and short, singular and multiple, vertical and horizontal, defined and blurry, and shapes and lines” [6]. Increasing the contrast between objects gives the piece more character and balance [6]. Objects within a painting should have relative balance with each other (Figure 3.3), and they should not be evenly balanced (figure 3.2) [6]. A fascinating technique he discusses is the use of three-line integration. The objects should cross and interact with each other (as shown in figure 3.4) without being parallel to each other. There should be one dominant line and two other minor lines [6]. Chinese painters also organize their compositions around a shape or series of movements to capture the viewer’s attention (figure 3.5 & 3.6) [6]. Zhen also emphasizes the use of white spaces, which allows the viewer to fill in the gaps with their imagination [6].

To gain more insight into the standards of creating a Chinese painting, I read about Hsieh Ho’s (497-501) six principles of painting in another secondary source (Briessen’s The Way of the Brush Painting Techniques of China and Japan). They include rhythm/movement, use of the brush, outline correctness, appropriate colors, composition, and copying/transmission [4]. These broad but famous principles have been followed for centuries.

Other notes about my process:

I worked on the branches closest to the edges of the paper first before filling in the middle (to make sure I can fit the entire painting onto the page).

To prevent color contamination, I wash the brushes in a cup of water and wipe it on a paper towel between different colors.

Towards the end, I went back and painted another layer above the branches and leaves to enhance the colors.

I alternated between the traditional way of holding the brush and my usual handgrip, depending on what I was painting.

I held the brush in the traditional way to make long, sweeping movements across the painting. This makes the strokes appear more natural.

I held the brush in my usual way to stabilize the faulty brush and add finer details.

This piece took four nights (Apr 16-19) to finish. I painted in 2-3 hour blocks.

Detailed Painting Steps—

After the preparation stage, I began to paint the branches with a flat brush. The branches served as the main guideline for the entire piece.

I then used the thin, pointy brush to add the leaves with the green color.

Then I added the flowers and petals with the pink.

Next, I added fine details (red dots and green leaf shapes) to the flowers, imitating how Chen Chun paints his blossoms.

I added details on the leaves with a 0.45 mm black Micron Pen.

I then added small white blossoms. The stems were painted green, and the blossoms were outlined with gray paint. Details were also added (yellow centers and red dots).

I painted the rocks on the bottom left a gray color, making sure not to cover the branches & details above them. I painted the grass green by making rapid brush strokes.

I attached a pre-cut piece of white sketchbook paper to the painting with double-sided tape.

Issues & Adjustments:

- The colors would sometimes bleed across the paper and create fuzzy outlines. To prevent this from happening, I adjusted the water to pigment ratio by using less water and more pigment. I also dabbed off any excess water from the paper with a soft tissue to keep the outlines crisp.

-The colors appeared dull on the delicate rice paper because it’s slightly transparent. To make the colors more vivid, I attached a piece of white sketchbook paper to the painting. This also gives the painting structure.

-Chen Chun used black, opaque paint/ink to add the details on the leaves. It was difficult for me to create a black opaque paint with the watercolors without it being too dry and unusable. I used a 0.45 mm waterproof Micron pen to create these details instead. Because this pen nib was fairly thick, I had to adjust my hand pressure to create smooth, thin lines that measure closer to 0.2 mm.

-The metal insert (ferrule) of the thin, pointy brush was loose and unstable. I attempted to repair it before painting but failed. I ended up having to hold the brush in my usual way to stabilize the bristles.

Reflection

Improvements —

There are a couple of ways I could have improved my work. During the reworking process, I realized how the quality of painting materials can greatly impact the results. Another scholar who also wants to replicate a Chinese composition should consider purchasing high-quality tools and materials to get the best outcome.

The watercolor paint pans I used were a couple of years old and student-grade. Since the quality of the paints deteriorated over time, I was unable to use a few colors because the pigments would not dissolve in water. The colors were also very transparent and dull compared to the colors in Chen Chun’s work. Because of time constraints, I just used my own watercolor set instead of ordering more paint. If I were to recreate another Chinese painting, I would purchase artist-grade tubes of watercolor paint instead. Paint that comes from a tube is usually more vibrant and easier to mix with water.

The size of my illustration is significantly smaller (5.4 in. by 9.4 in.) than Chen Chun’s piece, which is 12 13/16 in. by 22 9/16 in. [1]. Because of how small the paper was, it was difficult to add noticeable details to the piece. If I decide to recreate another Chinese painting, I would purchase a larger piece of paper and trim it to the actual size of the target painting. This would give me more space to add all of the intricate details.

The quality of the brushes I used also interfered with my painting process. The ones I used were soft and retained a lot of water & pigment. Because of this, I quickly used up the colors I originally prepared and had to repeat the mixing & color matching process again. This was time-consuming and led to inconsistent colors. Next time, I would use a firmer, less absorbent brush to mix the colors and use 3 tubes of the primary colors (red, yellow, and blue) as Zhen did. This would allow me to mix larger amounts of paint that would be enough to complete the entire painting. I would also record the color mixing recipes and ratios for future reference in case I run out of a specific color.

The Shuan paper I ordered is fairly fragile and transparent. There are also random green leaves that are woven into the white fibers. I did not realize this until I received the paper. They seemed out of place, so I picked them out. This created thin and weak spots within the paper. To avoid this, I will attempt to purchase thicker, more homogenous Shuan paper from a different manufacturer in the future.

The extra tools Zhen mentioned in his book would have been helpful for my painting process. For instance, the masking fluid can prevent the pigment bleeding issues I was experiencing and allow me to create crisp details without interfering with the layer below.

What I Learned—

This rework project deviated from my previous painting experiences. I usually create a pencil sketch before adding any watercolor paint to my compositions, but this method is not suitable for this type of painting. The pencil and eraser could easily damage the delicate Shuan paper. Sketching could also make the composition appear less natural and “flowy”. I had to minimize the number of mistakes I made because it is hard to remove pigments from the paper without ripping it. This was stressful for me at first, but it allowed me to learn how to paint more freely and naturally without getting too focused on replicating the piece exactly. Even though the precise positioning of the details does not match the target painting, I attempted to replicate the movement of Chen Chun’s brush strokes.

I also learned more ways to improve my own compositions from reading Zhen’s insightful book. I will incorporate Zhen’s composition secrets into my future illustrations. Chen Chun also integrates several of these secrets into his Garden Flowers painting. His use of white space, line contrasts, and 3-line integration explain why I was drawn to this painting.

Is Imitation Art?—

There is a common belief that individuals who imitate artworks by other artists are low-skilled and uninventive. After completing this project and reflecting upon the process, I would argue that this is not the case. I believe that it is crucial for artists to imitate other works in order to develop their own painting skills and techniques. Apprentices in the Dafen painting factories are able to sharpen their own painting abilities under teachers/masters by replicating famous artworks, and they go on to pursue independent careers with these talents [5]. The ability to “copy the old masters” is actually one of the valued principles of painting by Hsieh Ho [4].

Painters in such factories also develop their own creative methods to fulfill orders more efficiently, such as using “grids, stencils, overhead projectors, blue transfer paper” and corn starch on paper [5]. I also incorporated various methods/adjustments to make the painting process easier and to create the most accurate replica possible. This includes using my micron pen to add tiny details and adjusting water to pigment ratios when needed.

Dafen painters eventually learn the paintings and could illustrate them without referencing the original painting. Towards the end of the painting process, I glanced at the reference painting occasionally (to determine the relative position of the objects) and mostly drew from imagination. Throughout the reconstruction process, I had to think creatively and utilize any available materials resourcefully to achieve the most accurate copy.

Sources

Primary Sources

[1] “Garden Flowers” Met Museum, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45797. Accessed 25 Apr. 2022.

[2] “Summer Garden.” Metmuseum.org, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45802. Accessed 25 Apr. 2022.

Secondary Sources

[3] Barnhart, Richard M. Peach Blossom Spring, NEW YORK, 1983, pp. 13–73.

[4] Briessen, Fritz van, et al. The Way of the Brush Painting Techniques of China and Japan. Tuttle, 1962, pp. 40-196.

[5] Yin, Wong Winnie Won. Van Gogh on Demand China and the Readymade, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2014, pp. 39–53.

[6] Zhen, Lian Quan. Chinese Watercolor Techniques for Exquisite Flowers, North Light Books, Cincinnati, OH, 2009, pp. 10–41.