Japanese Woodworking Workshop

Japanese Woodblock Printmakng, also known as mokuhanga, 木版画 literally translates to “wood printmaking.” During the Edo period (1603-1867), the original Chinese precedent refined into the multicolored woodblock technique of Japan. Some of the earliest woodblock prints were black and white Buddhist sutras from the 8th century, leading up to the widely celebrated ukiyo-e. The prints produced from woodblock printing allowed the growth of literacy in early modern Edo, reproducing books, advertisements, shop signs and individual prints as well. Ukiyo-e, also known as "pictures of the floating world" glorified sites and life, expressing a growing urban popular culture at a time when the Tokugawa government continued to enforce a feudal class system. [4]

While the prints that come out of wooodblock printing have been widely circulated, the workshop and craftspeople are not as visible in texts.

The process of woodblock printing is simple- one carves a design out on wood, paints over it and creates a stamp of sorts to copy the design on to washi paper. The series of images below show the steps and process of creating a single color block.

Woodblock printing process- artist, carver, printer [1]

Diagram of ink transfer from wood block to paper

Woodblock print process- we can see how layered a single image is, and how it is split between blocks [1]

The woodblock printing process is typically broken up into four roles including:

Looking at the process of woodblock printing, I started to analyze spatially how some of the tools would look like in relation to each other in terms of scale.

What I imagine a woodblock painting table to look like

Using what was learned from the history and practice of woodblock printing- the project seeks to understand the the workshop and the practice of woodblock printing in a spatial, physical manner based off of the print of a woodblock print workshop by Utagawa Kunisada.

Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1865) was a woodblock print designer who produced more than 20,000 designs of woodblock print during his lifetime. He also would print and carve his designs as well. The majority of his designs were kabuki and actor prints, however he was also active in Bijin-ga 美人画 prints which made up about fifteen percent of his collection as well. To represent artisans, Kunisada would replace the men more typical of the theme with women. [2]

I started by first analyzing the image itself, seeing who the characters are and programmatically what they were doing. In this case, we see steps involved in carving and printing, but not the publisher or artist. This shows that typically these steps took place outside of the workshop. We can also see that the image appears crowded- with minimal space in between people. In general it is hard to see the flow of the workplace. There does not seem to be a sense of path, or a sense of order in their steps. Since final prints are not shown it is difficult to see the concept of time in the image as well. Another interesting point is that the process of sharpening tools is depicted, but the act of painting or moment of ink transfer is not. Sharpening tools- while being a key aspect of carving- is not a main step.

Based off of basic proportions of people sitting down, an initial digital model was made.

Initial digital model

[7]

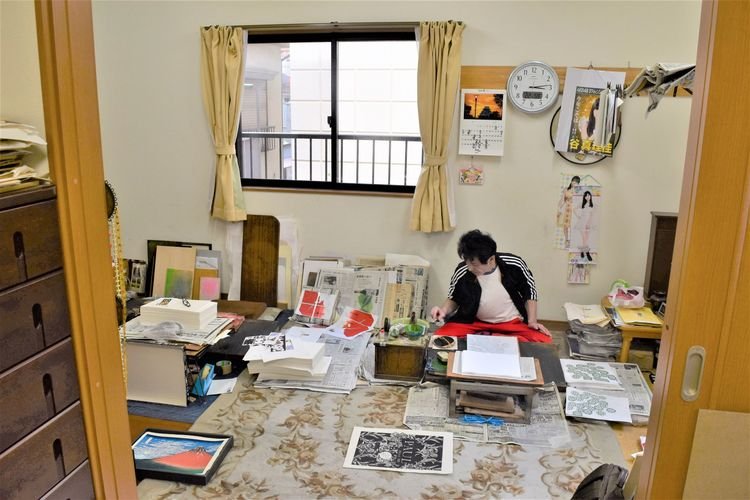

After an initial investigation and attempt, I researched modern day woodblock printing workshops. The videos not only show the steps but also how the craftspeople move. Each of the craftspeople who have their individual roles have their own low table- similar to a work cubicle. The carver, once done with their blocks would walk over and hand over the blocks to the printer. In all of the examples I saw the tables are always low to the ground and that no part of the step is done standing. This is probably because sitting is the most stable person, and also to eliminate as much physical strain and fatigue as possible. What we see in the videos is how craftspeople are surrounded by tools, even in steps besides painting. Different sizes of tools and shavings are seen everywhere. While this is still true in Kunisada’s print, each of the tools seem bare- not covered by a case or covering. We also see how craftspeople preferred to be in direct sunlight when printing. Some would even add an extra light above their workplace. I thought this was interesting since especially for painting, the water based paint will dry quickly in sunlight but in this case sight was prioritized. In these modern day workshops, it seems like one carver and one painter are designated per design. Depending on how many layers were needed would determine the timeline. As we see in Kunisada’s print, there seems to be multiple carvers. This is probably because there is less of a demand for woodblock prints, and is now more seen as an art than a commodity. We can afford to have one person designated to a role.

Using traditional shoji screen dimensions and dimensions of people sitting, I started to understand and draw out the workshop. Table dimensions were calculated looking at the size of sheet of washi used in Ukiyo-e prints which are 15.5 inch by 20 inch. Using that and looking at Kunisada’s print, we can start to see the proportions of a table- how most of them were fairly long but the one with the artisan wetting the paper is small. Something that surprised me was how much space they had in between work tables. Typically a walkway is three feet wide, and there seems to be plenty of space in the model, however not in the image. This is also because there is little to no sense of depth in woodblock prints.

Floor plan showing walkway space

After refining my original 3D model, I started to model the space out of basswood, trace paper, construction paper, and bristol paper. I then added the people scaled to align with the tables (which are built at 1”=2’ scale)

Process 3D modeling

With this final model, one can see how skewed the sense of depth and proportion are but also be able to see the space in 3D.

Reflecting on this process of creating and imagining a workplace three dimensionally, some questions still remain unanswered.

Where are these workshops located? What is surrounding them?

How much movement coming in and out of a workshop is there?

Where are the door(s)?

Having created the workshop three dimensionally, I noticed how flexible the workshop is- something that seems to align with Kunisada’s print as well. Comparing it to something like Washi papermaking, the steps leading to a woodblock can be done with a low table and a few tools. The only table that can not be moved, or one that requires more manipulation is the printing table since it requires pigments and more tools than the other steps. I initially assumed that a print factory would be very wet- having to wet the paper and also with using pigments as well. However, after constructing the model and with research, I realized that these areas of wetness are more controlled than the areas or zones of dry.

Looking at the initial print from Kunisada to the final model, while I learned about Japanese woodblock printing, I also learned and investigated about interpretation of spaces as well. Woodblock printing, while each step is individualized, is a collaborative work. Perhaps Kunisada wanted to show the craftspeople’s dependence on each other and highlight their teamwork with this print.

[1] “A Guide to Japanese Woodblock Print.” Japan Craft, March 27, 2017. https://japancraft.co.uk/blog/japanese-woodblock-print-guide/.

[2] Metmuseum.org. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/55723.

[3] Salter, Rebecca. Japanese Woodblock Printing. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2013.

[4] Vollmer, April. Japanese Woodblock Print Workshop: A Modern Guide to the Ancient Art of Mokuhanga. Berkeley: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2015.

[5] “【職人技】伝統木版画ができるまで - Youtube.” Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5R_QnXL8qLA.

[6] “手技tewaza「江戸木版画」Edo Mokuhanga ... - Youtube.” Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZlDX28PUsjU.

[7] “松崎大包堂さんで江戸木版画体験!.” ワゴコロ. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://wa-gokoro.jp/traditional-crafts/550/.