Hwajeon, Flower Rice Cakes

These days, rice cakes are nearly synonymous with Korean cuisine. Oftentimes, the foreigner’s knowledge of rice cakes is limited to tteokbokki, spicy stir-fried rice cakes. In reality, there is a wide variety of Korean rice cakes that includes recipes that have been lost long ago or reserved for a certain class of society. One of the most interesting categories of recipes are rice cakes that are still made in modern cuisine, but differ from historical methods. Hwajeon, or a flower cake, is one such recipe. Here, I attempt to recreate historical versions of hwajeon from archival cookbook sources.

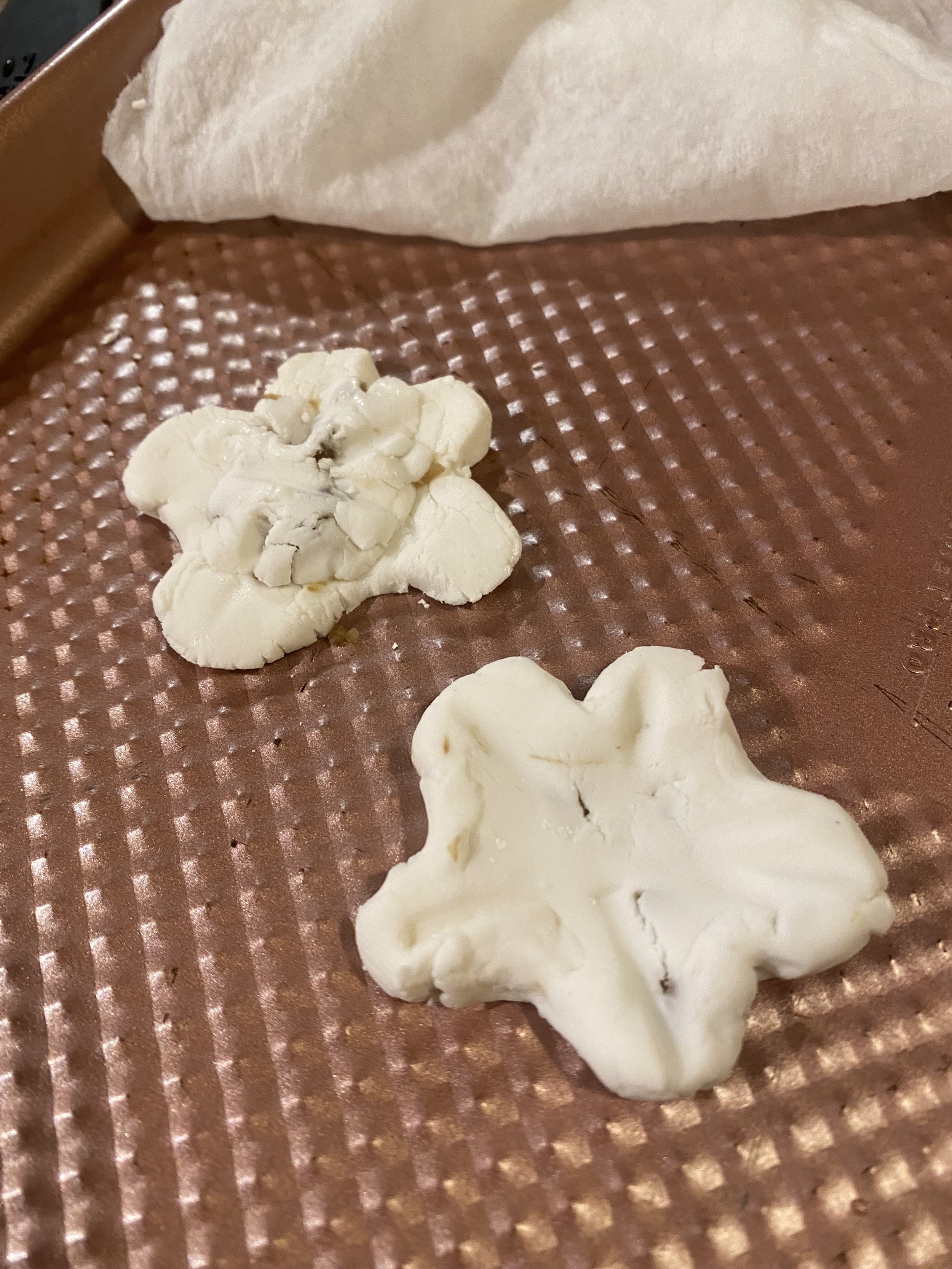

Fig 1: Modern Hwajeon

All of the information for this particular culinary experiment comes from historical cookbooks, especially cookbooks written by women. Cookbooks written by female writers are unique in Korean culture, because they depict larger social trends that manifest themselves in the kitchen. Scholar Ro Sang-ho speaks on this phenomenon, saying that “the Korean traditional kitchen symbolized gender segregation and the societal hierarchy in which women prepared the food and men ate it” [3]. Women were almost exclusively relegated to the kitchen, especially the domestic kitchen, but were largely excluded from cookbook writing for most of history. This practice was based on the “strong tradition of apprenticeship, [which] basically barred men from any involvement in the kitchen” [3]. Apprenticeship in the kitchen meant that culinary knowledge gained some level of exclusivity. Women shared their skills and knowledge with other women through word of mouth, not through written methods. As such, women “valued little the practice of writing and reading in their professional training. Unless a yangban man was so interested in cooking as to learn it from a female slave, the kitchen remained a foreign sphere to the literate man” [3]. In the last century or so, women have begun to value written knowledge and have taken charge of cookbook writing, highlighting the largely female kitchen culture. But the practice of apprenticeship is still indispensable in the production and communication of culinary knowledge. The tacit knowledge one gains from an apprenticeship is necessary to fully comprehend how to read and write these Korean cookbooks. They assume a certain level of background knowledge, often leaving out specific details or instructions that the novice or unfamiliar cook might not know.

The traditional Korean kitchen - women preparing rice cakes and soy

The result of female apprenticeship in the kitchen, the higher value of tacit knowledge vs written knowledge in cooking, and the lack of men in the culinary sphere have all created a segregated kitchen culture based on gender. Women typically have the tacit knowledge to both write and read cookbooks effectively. Men, especially of the higher classes, generally lack the culinary knowledge to be able to write effective cookbooks or comprehend them enough to recreate the dishes that they discuss. Given all of this information, the main sources I relied on in my experiment come from female writers. While I do reference one source written by a man, the works by women are more useful when figuring out how to read between the recipe’s lines.

Background

Before preparing hwajeon, I also thought it would be helpful to know more about the general history of Korean rice cakes. I was hopeful that this background information could give more more clues about ingredients and preparation methods. Rice, of course, is the basis for all rice cake recipes, including hwajeon. Michael J. Pettid, professor of Korean studies, notes the “relative uncommonness of eating rice among lower social groups”, so it was largely reserved for special occasions (34). Rice cakes were prepared by pounding rice using “heavy wooden mallets made from hardwood” [2]. The pounded rice was then formed into a rice cake press to create “auspicious designs and shapes” and often cooked in a “special earthenware steamer used for making siru ttǒk (steamed rice cakes)” [2]. As evidenced by the basic process outlined here, rice cakes were fairly labor intensive and rice was an ingredient typically reserved for special occasions, meaning that most rice cake recipes were limited to certain occasions and holidays.

Pounding rice using a wooden mallet

Luckily enough, Pettid mentions the brief history of hwajeon in his work. The third day of the lunar month (Samjitnal), “when the swallows return from the south and thus marks the advent of spring and the beginning of the farming season” is marked by a special food “hwajǒn, a flower cake” [2]. Pettid notes that festive hwajǒn were prepared by pounding the glutinous rice dough into small, flat circles, pressing azalea flowers into the cakes, then frying them in sesame oil. Some regions also topped the cakes with honey for an even sweeter snack. [2]. All of this suggests that hwajeon was typically a holiday treat. But outside of the lunar month, the exclusivity of ingredients and labor intensive nature of rice pounding indicates that it was most likely reserved for higher classes and maybe even the imperial court.

Recipes

The first recipe comes from Lady Yi’s (1759-1824) Kyuhap Ch’ongsŏ (The Encyclopedia of Daily Life) a household management aid that she wrote for her daughters and daughters-in-law. Lady Yi is a high status woman from the late Chosŏn period who wrote the work as a guide to household management and cooking.

“As the color will be yellowish and it will require a lot of oil if kneaded with cold water, make dough with boiled saltwater. Knead it until it does not break apart when grabbing by the hand and make cakes in the shape of chrysanthemums. Place them on a flat tray, put chestnut stuffing in them, and make thin lines with a tweezer.

It is good to add a lot of azaleas and roses but will be bitter if too much chrysanthemum is used. It is also good to pan-fry after removing the green stalks of chrysanthemum and coating with flour.”

My summary of Lady Yi’s recipe is summarized like this:

Add salt to water

Heat salt water until boiling

Cut rose petals into small pieces and mix into glutinous rice flour.

Chop chestnuts into small pieces.

Add honey into chopped chestnuts until moistened.

Add boiling water into glutinous rice flour mixture until it can be kneaded without breaking apart.

Pinch off a piece of dough and shape it into a flower using fingers.

Place chestnut honey filling in the middle of the first piece of dough.

Press another piece of dough on top of the filling until enclosed and as flat as possible.

Heat vegetable oil in a frying pan until hot.

Thinly coat the shaped rice cakes in glutinous rice flour.

Fry rice cakes in hot oil until they are a light, golden brown.

The second recipe is translated from Eumsik dimibang, written around 1670 in Lady Jang during the Chosŏn dynasty. Lady Jang also hails from the yangban class and wrote the book in the Korean alphabet.

“Use petals of azalea, rose, or peony. Mix into the glutinous rice flour a bit of hulled buckwheat powder and plenty of flower petals to make [the dough] soft. Boil the oil and lay them out separated from each other, frying them frequently over strong fire. After a wisp of steam, serve them with honey.”

My summary of Lady Jang’s recipe is summarized like this:

Add salt to water

Heat salt water until boiling

Cut rose petals into small pieces and mix into glutinous rice flour.

Add buckwheat powder into the rose and rice flour mixture.

Add boiling water into glutinous rice flour mixture until it can be kneaded without breaking apart.

Pinch of a piece of dough and roll it into a ball, then flatten into a round thin disc.

Heat vegetable oil in a frying pan until hot.

Fry rice cakes in hot oil until they are a light, golden brown.

Serve with honey.

The last recipe comes from Sŏ Yugu, Madame Yi’s brother-in-law. His encyclopedia Writings on Managing Rural Life briefly mentions hwajeon in a section about stir-fried rice cakes. It reads:

“There are various kinds of oil fried rice cakes. Among them, the one in which [the petals of] azalea, rose, peony or other flowers are mixed with glutinous rice flour and fried is called flower stir-fry rice cake. Also among them is the stir-fried pancake, using only flour and water to make the dough, spread thin and then made into approximately the size of the mouth of a rice bowl, and fried. Sometimes glutinous rice flour, sorghum flour or Adlay powder is used. There are variations in shape and method of making depending on the ingredient, but they are almost all the size of the mouth of a cup. Also, using mashed adzuki bean paste as filling is also called stir-fried pancake.”

These recipes all assume a working knowledge of Korean cooking and rice cake preparation. The lack of specific measurements and details in the recipes is indicative of the assumption of tacit knowledge. Sŏ Yugu’s version is relatively vague and may be suggestive of his limited hands-on knowledge in the kitchen as a yangban man. There are also large discrepancies between Madame Yi’s and Lady Jang’s recipes- stuffing vs no stuffing, buckwheat powder and glutinous rice flour vs just glutinous rice flour, and the types of flowers used. These discrepancies may be based on a conscious decision by the authors’ to exclude certain pieces of information, based on assumptions of background knowledge, or may be attributed to differences in family recipes, regions, and personal taste. Either way, I believe it is effective to produce both in order to compare them.

My first obstacle came with sourcing ingredients. Chrysanthemums, peonies, and Korean azaleas were difficult to find based on my location and seasonality. As such, I was forced to use white roses. Instead of pounding rice using a wooden mallet, I was able to find glutinous rice flour, which was almost undoubtedly of a better quality and texture that I could ever achieve myself. Additionally, the biggest question for me was the type of oil I should use for frying the cakes. My first instinct went along with Pettid’s comment about sesame oil, but upon further research, it seems that sesame oil was mainly used for seasoning and cooking vegetables, and not often used for frying. So, I decided to use a flavorless vegetable oil to fry the cakes for both recipes. The lack of specificity left much of the process up to me and my own flavor and texture preferences, which seems to be in line with the original intentions of the writers, to guide women through recipes, but give them the flexibility to alter the recipes based on their personal tastes.

My ingredients- white roses, roasted peeled chestnuts, glutinous rice flour, natural honey, water, salt

Madame Yi’s “Flower Cakes” Hwa-Jŏn

Honestly, I felt a bit overwhelmed before beginning the recipe, given the lack of specificity and measurements. I realized that I would have no choice but to rely on flavor and textural hints, as well as my own intuition. I started with 1 cup of glutinous rice flour and slowly adding hot, boiled saltwater (2 cups of water with ½ tsp salt), and 3 rose petals, because I know that rose can easily be overwhelming. For the chesnut filling, I decided to finely chop chestnuts and mix them with a bit of honey, until moistened and lightly sweetened to the taste. The addition of honey was based on Madame Yi’s other rice cake recipes that feature chestnut honey fillings. I was able to follow all of my summarized steps with a reasonable level of success, except for the filling. The first cake I tried to place the filling on top of the first layer, then encase it with extra dough on top. This method did not work because it was messy and difficult to encase the filing. Instead, I formed a cup of dough where I placed the filling, encased it by rolling it into the ball. Then, I flattened the ball and shaped it into a flower using a pinching motion with my fingers. Once they were finished, I gave them a taste. I would say they were successful, but the flavor was fairly bland. I could not taste the rose, chestnut, or the honey. But honestly, the rice cakes seemed so small that the filling was almost nonexistent and difficult to taste at all.

Lady Jang’s “Method of Making Stir-Fried Flower [Rice Cake]” 煎花法(chŏnhwa pŏp)

Making Madame Yi’s hwajeon made me a lot more confident when recreating Lady Jang’s version. This time, I started with ½ cup of glutinous rice flour and added in about 1 tbsp of buckwheat powder and a total of 6 rose petals, to hopefully amp of the rose flavor. I followed the same steps to mix the dough into a homogenous mixture that could be shaped and rolled without crumbling. This recipe did not have a filling, and shaping it was much easier because it just included forming it into small, flat discs. After frying them, the texture was chewy, as expected from glutinous rice flour. The accompanying honey definitely made the cakes sweeter and more flavorful, but the rose was still nowhere to be found. Also, the color came out much darker than I would have expected, but nothing in the recipe indicates the desired color or amount of buckwheat powder. Either way, I preferred this recipe. It required less work, and the flavor of the honey on top really made the entire dish more enjoyable.

Reflection

While my culinary experiments were successful, I still did not feel the satisfaction of complete success. My own tacit knowledge in the kitchen was extremely helpful when recreating these recipes, but, like a yangban man, my lack of tacit knowledge in the Korean kitchen and with rice cakes in particular makes it difficult for me to know exactly how these dishes should taste, look, and feel. Ultimately, it seems that those with kitchen experience can create these recipes, but ultimate success depends on their own personal preferences. These recipes seem to be general guides, not specific and detailed recipes that have to be followed to a tee.

The finished hwajeon

[1] Andong, Chang S. Umsik Timibang. Taegu Kwangyoksi: Kyongbuk Taehakkyo Ch'ulp'anbu, 2003. Print.

[2] Pettid, Michael J. Korean Cuisine: An Illustrated History. Reaction Books Ltd, 2008.

[3] Sang-ho, Ro. “Cookbooks and Female Writers in Late Chosŏn Korea.” Seoul Journal of Korean Studies, vol. 29, no. 1, June 2016, pp. 133–157. Project Muse.

[4] So, Yu-gu, and Chong-gi Chong. Imwon Kyongjeji: Umsik Yori Paekkwa Sajon. , 2020. Print.