Legend and Legacy: An Exploration of Jiaozi throughout history

Project Introduction

Jiaozi have become ubiquitous in nearly every culture in the world, taking a wide variety of forms and informing consumers about the material and culinary fabric of the culture they inhabit. For this project, I wanted to track the dumpling from its origin nearly two thousand years ago to its modern status as a hallmark of Chinese cuisine, a food that represents China’s evolving attitudes toward food as an art form. This project aims to capture the trajectory of dumpling from its conception for medicinal purposes to its evolution at the hands of foreign interaction to its modern interpretation in the Qing dynasty. In order to do so, I chose to recreate dumpling recipes from three distinct periods of Chinese history using information gathered from my primary sources.

Making the dough

All three recipes call for the same type of dumpling dough, so it is a natural starting point for this culinary journey

Because none of the primary sources provide detailed information about the dough-making process, I chose to follow the guide of the video that is attached below [3]. Given that it is a two-ingredient food, it is likely that the process has not changed significantly since the time that my primary sources are from.

Ingredients:

2 cups all-purpose flour

2/3 cup water (room temperature)

Steps:

Sift flour into a large bowl. Slowly pour in the water while constantly mixing with a pair of chopsticks.

Continue to mix until the flour is moistened and the dough is shaggy. Begin kneading to form the dough into a ball. At this point, the dough will be quite tough and should not be sticky.

After forming the dough into a ball, dust the working surface with flour in order to prevent the dough from sticking. Place the dough on the working surface and knead for 8-10 minutes or until the dough is fully blended and is smooth.

Transfer the dough back into the large bowl. Cover the bowl with a damp towel and let the dough sit for 1.5 hours.

Dust the working surface and your hands with extra flour and transfer the dough onto the surface. Knead the dough for another 3 to 5 minutes until the dough hardens again. Let the dough rest for about 30 minutes. At this point, your dough should be fluffy and should regain its shape after being poked.

Cut off a piece of your dough and roll it into a long cylinder of about an inch’s diameter. Cut into inch-wide pieces and sprinkle with flour on both sides.

Press the pieces into round discs and roll with a rolling pin (or wine bottle in a pinch) into a round sheet. It should be around 1mm thin and 3 inches in diameter.

Scoop 1 tbsp of filling into the center of your wrapper. Holding the wrapper with one hand, seal the edges around the filling with the other. Make sure you seal well so the dumpling does not fall apart while boiling.

Recipe 1: Zhang Zhongjing’s medicinal dumpling

The first recreation is inspired by the work of Zhang Zhongjing, who is credited with inventing the dumpling nearly two thousand years ago as a medical remedy for villagers with frostbitten ears – hence the “ear” shape that we form dumplings into even to this day [5]. Zhang is known primarily for his contributions to the medical field, and he is often referred to as the father of traditional Chinese medicine; his work influences practices in the field up to the present day. His most notable work, Shanghan Lun (On Cold Damage), was originally written during the Han period and later compiled during the Jin, and it contains several hundred pages of herbal prescriptions and medicinal cures for “externally contracted disease…ascribed chiefly to contraction of wind and cold” [6]. Details surrounding his personal life are realtively scarce, but he lived through a time of continual warfare in the Han which fostered multiple epidemics, inspiring Zhang to begin cataloguing patterns of illness — a medical concept far ahead of his time [6]. On Cold Damage was a corpus of knowledge unlike anything Chinese scholars had seen before, and it remains the pinnacle of ancient medicinal texts in the Chinese canon.

In order to try and recreate what may have been the first dumpling ever invented, I took inspiration from his recipe for gui zhi tang (Cinnamon Twig Decoction), a medicinal tea that aims to “resolve the fleshy exterior, dispel wind, and harmonize the construction and defense” when dealing with severe cold and frostbite [6]. Combining his recipe with the origin story of the dumpling, I decided to make a dumpling that incorporated this recipe along with a meat that would have been common at the time: mutton. This idea is depicted in the video below. While there are obvious complications with this construction (as will be addressed in the discussion), I feel that this is a strong way to mark the beginning of the dumpling’s story.

Original Text:

“In greater yang wind strike with floating yang and weak yin, floating yang is spontaneous heat effusion, and weak yin is spontaneous issue of sweat. If [there is] huddled aversion to cold, wetted aversion to wind, feather-warm heat effusion, noisy nose, and dry retching, Cinnamon Twig Decoction (gui zhi tang) governs…

Cinnamon twig, 3 liang (remove bark)

Peony, 3 liang

mix-fried licorice, 2 liang

fresh ginger, 3 liang

jujube fruit, 12 pieces” [6].

Ingredients

Ground cinnamon

Dried licorice root, ground

Fresh ginger, finely chopped

Jujube fruit, seeds removed and cut into small pieces

Whole peppercorns

Salt

Ground lamb

Steps:

In a mortar and pestle, grind together the licorice, peppercorns, cinnamon, and salt until fine.

Add the ginger and jujube and grind into a paste.

Stir the paste into the finely chopped mutton.

4. Scoop 1 tbsp of filling into the center of your wrapper. Holding the wrapper with one hand, seal the edges around the filling with the other. Make sure you seal well so the dumpling does not fall apart while boiling.

5. Place sealed dumpling into a pot of boiling water and let sit for around 2 minutes or until the dumpling floats to the surface and sits for a minute.

6. Remove from water and immediately place on a plate.

Final Product

Zhang Zhongjing’s medicinal dumplings

Recipe 2: “Päräk Horns” from the Yuan Dynasty

The second recreation comes from the Yuan dynasty, which was indelibly marked by Mongol expansion. Accordingly, the recipe I used comes from a cookbook that reflects the influx of new culture and ideas that came from this conquest. As Mark McWilliams explains in Wrapped & Stuffed Foods: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, “The Mongol invasion of China and the Mongols’ establishment of the Yuan in 1271 brought with it a wave of influences from central Asia” [2]. With that influence came new methods of cooking dumplings, as captured in A Soup for the Qan: Chinese Dietary Medicine of the Mongol Era As Seen in Hu Sihui’s “Yinshan Zhengyao.” Hu, an imperial dietary physician who presented Yinshan Zhengyao to the emperor as a dietary manual, continued the connection between food and medicine established by Zhang Zhongjing. As the translators of A Soup for the Qan observe, “Since Hu’s primary interest and charge was the medical aspect of nutrition, always a central focus in the Chinese world, much of the book is an account of the medical values of foods and recipes, in terms of Medieval Chinese nutritional therapy” [1]. Thus, his work not only demonstrates the “deliberate construction of a cuisine to reflect the scope of the empire” by incorporating new ingredients from the edges of the Yuan, but it also shows the relationship between new and old, a heterogenous mixture of classic Chinese medical practices and Mongol and west Asian influences [1]. The emperor indeed would be impressed by the swathe of cultures under his control as demonstrated by this food. Look no further than the fact that this recipe calls for the dumplings to be baked and drizzled with honey and butter rather than to be boiled or steamed in traditional fashion; yet, it still uses the mutton we saw from Zhang’s original dumpling.

Original Text:

“Mutton, sheep’s fat, sheep’s tail, young leeks. (Cut up each finely).

[To] ingredients add spices, salt, and sauce and mix [everything] together uniformly. Use white flour to make the skins. Bake on a flat iron. When done, then use liquid butter and honey. Perhaps one can use pear-shaped bottle gourd meat to make stuffing. This is also possible” [1].

Ingredients

Leeks

Salt

Pepper

Honey

Butter, melted

Steps:

Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

Cut off the root and the tough green top of the leek. Slice the remaining part of the leek in half lengthwise, then cut into thin slices that look like ribbons.

Clean the leeks in a bowl of warm water to ensure no dirt or sediment remains. Remove the leeks from the water and dry them on a paper towel.

In a medium bowl, add the mutton, leeks, salt, pepper, and mix until combined.

Place filling inside wrapper and close.

Place filled dumplings on a greased baking tray and bake in oven for 20-25 minutes or until bottoms are a light golden brown.

After removing baked dumplings from the oven, drizzle melted butter and honey over the top.

Final Product

Päräk Horns

Recipe Three: Yuan Mei’s Classic

Finally, any reconstruction of Chinese culinary history would be incomplete without the presence of Yuan Mei, the landmark Qing dynasty painter and poet whose many writings on food mark a critical point in China’s relationship with food. The recipe I chose to recreate comes from Recipes from the Garden of Contentment: Yuan Mei’s Manual of Gastronomy, which is the product of forty years of Yuan’s work compiling recipes from various chefs during his travels. Because he received these second-hand and often incomplete, many of his “recipes” are not what we consider recipes but rather suggestions or comments on the dish as he recalls it. Because of this, the recipe I chose – a pork dumpling recipe – needed a modern supplement. I chose the recipe from an online source for its adherence to the cultural tradition of Chinese flavors and its relative simplicity. There are no overly complicated procedures or extra ingredients that one would not naturally associate with the dumpling in this recipe; Yuan’s tenets of simplicity in food-making would adhere with this recipe [4]. The experience of making this was quite similar to making his imitation crab recipe, where much outside research was required in order to actually understand what he is saying — even more so with this recipe because of the lack of ingredients or measurements.

Original Text:

“Flatten pieces of dough, fill them with pork, then steam them. Making these well is completely dependent on how the filling is prepared. Quite simply, the pork has to be tender, with any tendons removed, and then seasoned well. I’ve been to Guangdong and ate the dianbuleng of Garrison Commander Guan, which were excellent. The filling was made from pork skin that had been braised into a soft paste, which provided a soft and wondrous texture” [4].

Ingredients

Ground Pork

Sesame oil

Scallion

Chinese cabbage

Ginger

Garlic

Pepper

Rice vinegar

Salt

Soy sauce

Steps:

Combine the meat, soy sauce, salt, rice vinegar and pepper.

Wash and dry the cabbage (make sure you dry thoroughly). Finely chop until you are left with thin shreds.

Peel the ginger, scallion, and garlic. Finely mince all of them.

Add the shredded cabbage, garlic, scallion, ginger, and sesame oil into the meat mixture. Mix well.

Final Product

Yuan Mei’s Jiaozi

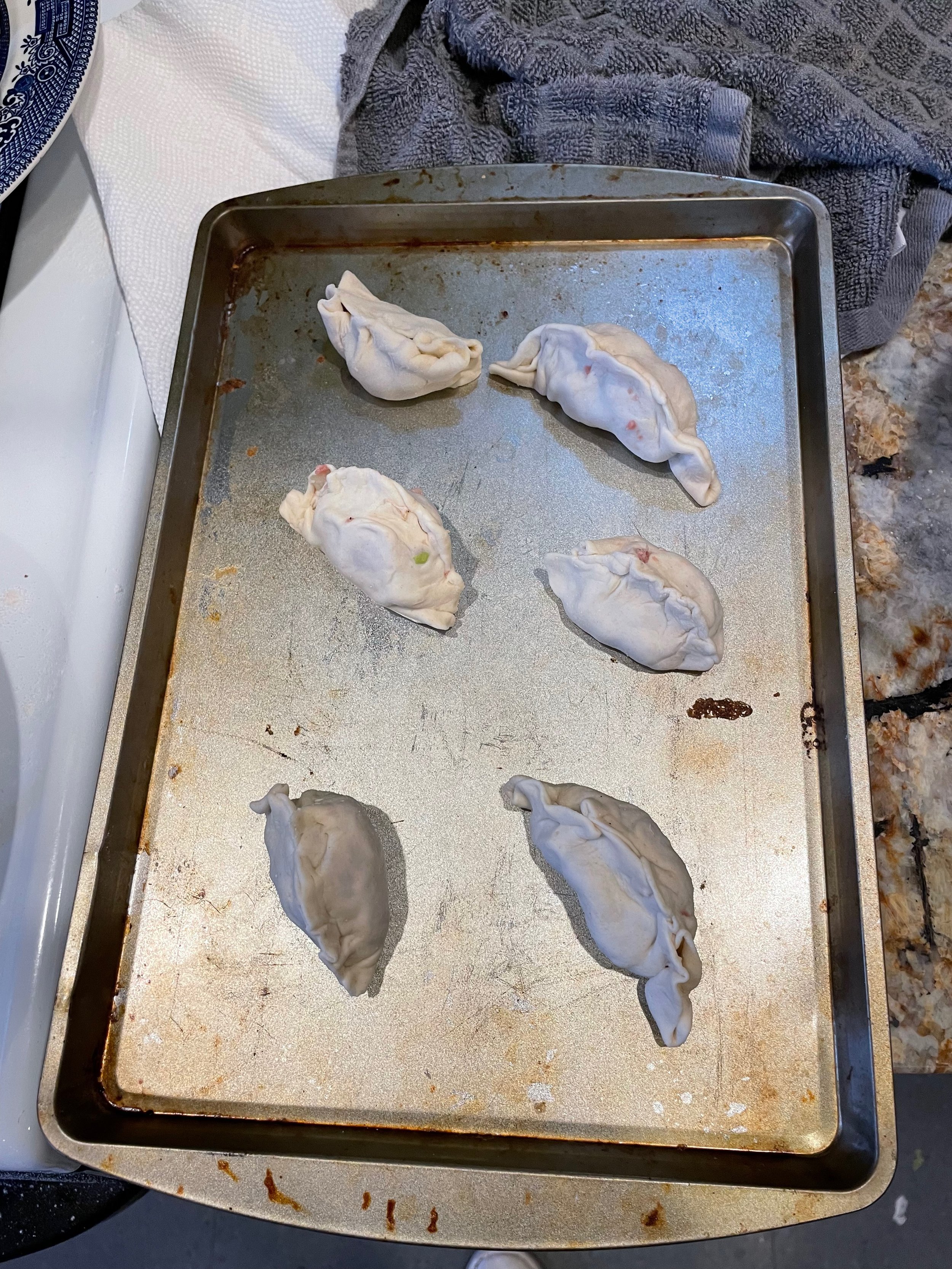

Issues with the dumpling dough

For the most part, I am pleased with how my reconstructions fared in terms of my ability to follow the recipes and create an accurate rework of these dumplings. However, there is one part, ubiquitous in every recipe, that caused me tremendous problems throughout several trials: the dough. I do not exaggerate when I say that I ran through two entire bags of flour in an effort to create a dough that would adhere to the guidelines from my primary sources. After researching extensively and trying different variations of water temperature, flour-to-water ratio and proofing time, I still struggled to create a light, fluffy dough that would retain its shape when poked (which I learned is the benchmark of a dumpling-ready dough). The product that I’ve included in the photos represents the best of those trials, but it still did not have that airy quality or fluffiness that I was looking for. I think it is safe to say that having completed this rework, I can assert only one thing for certain: I have an astounding paucity of baking talent. You can judge my kneading skills in the video below.

https://youtube.com/shorts/9otVBo3iEWU?feature=share

As the cooking process continued, because the dough had not properly proofed, it was much more difficult to roll out and prepare the dumplings for cooking. As a side note, I did not have a rolling pin, so I chose to use a wine bottle instead – surprisingly, it went swimmingly. Aside from that, however, the folding and crimping process was difficult because the dough did not have the pertness needed to create the distinct “half-moon ridge” that is characteristic of dumplings. As can be seen in the final product, the dough instead drapes around the filling like a robe, which is not ideal, aesthetically or otherwise.

Discussion and Reflection:

The justification for my rework is perhaps the most important aspect of the project given the particular angle I explored. Choosing to engage with a work as old as On Cold Damage and combining legend with written text comes with its flaws, and I will be the first to admit that. The reason I chose to take this step is because I believe it is an integral part of telling the story of the dumpling. Just as Yuan Mei’s writings are indicative of the way dumplings played a part in the culture of eating during the Qing, so too does Zhang’s writings help fashion the story of the dumpling’s genesis. And like many geneses, details are difficult to come by; as researchers, it is our responsibility to use our judgement to piece together the different parts into a unified whole. Perhaps my recreation did not resemble exactly what Zhang created nearly two thousand years ago, but the act of combining popular legend with legitimate historical document participates in telling the story of dumplings in a productive manner. Creating harmony between legend and history can help illuminate the ways in which certain things played – and continue to play – a part in a culture. This is the justification I provide for “bending the rules” of recreation, so to speak.

As I discussed earlier, the nature of Yuan Mei’s cookbook is such that many of his recipes, if recreated, would need supplementation, and so I again emphasize that a modern interpretation of his recipe is suitable for the purposes of this project. The only other alteration I made to the recipes was to use ground pork instead of pork tenderloin in Yuan Mei’s recipe and ground lamb instead of shredded lamb, which, given their close similarity and their being nearly identical in function, I feel is justified.

If I were to suggest ways of improving this rework for future research, I would begin by seeking out more primary sources, if there are any. While I feel that my sources can appropriately represent the evolution of dumplings over their long history, I also feel that there are other angles and recipes that may show another facet. Perhaps seeking out a recipe that takes influence from other East Asian countries or from another culture may help further develop the story of the dumpling, and therefore East Asian culinary culture as a whole. Also, if someone were to recreate the same recipes that I chose, I would suggest that they reduce the amount of jujube fruit in the recipe from Zhang. Secondly, of course, I would recommend that anyone who attempts this project figure out how to properly mix, knead, fold and proof their dough, as it becomes quite difficult to construct dumplings when the dough is not properly prepared (as discussed above). Finally, if one is to truly recreate the ways of Yuan Mei, I would suggest that they try to recreate the conditions that would have been available during his time. Yuan, in contrast to many of his contemporaries, preached the value of simplicity and modesty in cooking. This applies not only to the food itself but the manner in which it is prepared. Using as sparse materials and tools as possible would make for a more authentic culinary experience for both the chef and the consumer.

Works Cited

[1] Buell, Paul D., and Eugene N. Anderson. A Soup for the Qan: Chinese Dietary Medicine of the Mongol Era As Seen in Hu Sihui's Yinshan Zhengyao : Introduction, Translation, Commentary, and Chinese Text. Second Revised and Expanded Edition, BRILL, 2010. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.libproxy.wustl.edu/lib/beckermed-ebooks/detail.action?docID=634986.

[2] McWilliams, Mark. Wrapped & Stuffed Foods: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2012. Prospect Books, 2013.

[3] The History Channel. 2021. “The Original Chinese Dumpling Had a Unique Purpose | Ancient Recipes with Sohla.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EcqqhQqemxU.

[4] Yuan, Mei. Recipes from the Garden of Contentment : Yuan Mei's Manual of Gastronomy, edited by J. S. Chen Sean, Berkshire Publishing Group, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.libproxy.wustl.edu/lib/wustl/detail.action?docID=5987991.

[5] “Zhang Zhongjing.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/biography/Zhang-Zhongjing.

[6] Zhang, Zhongjing, et al. Shāng hán lùn: On Cold Damage: An Eighteen-Hundred-Year-Old Chinese Medical Text on Externally Contracted Disease. Paradigm Publications, 1999.