More Than a Snack: The Mooncake’s Journey from Street Treat to Cultural Icon

Introduction

Deeply entrenched in Chinese cultural practices and identity, mooncakes have grown to occupy a special place within Chinese culture, as the Chinese baking industry spends as much as 2.5 billion yuan a year on the production of mooncakes (Cui). Especially important to the Chinese Mid-Autumn Festival (中秋节), mooncakes hold important symbolism and cultural significance that has resulted in them being ubiquitous for all celebrating the Mid-Autumn Festival. Mooncakes have a long historical connection with Chinese rituals, with specific pastries being used in conjunction with rituals regarding the moon dating back to the Shang dynasty (17th century BCE – 1046 BCE). The earliest known record of specific mooncakes dates back to the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279 CE), with little surviving description of what these early mooncakes were like. Following the fall of the Southern Song Dynasty came the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368 CE), and while direct historical records from the Yuan dynasty about mooncakes are limited, legend holds that mooncakes were used to pass messages in a rebellion that contributed to the fall of the Yuan dynasty. After the Yuan dynasty came the Ming dynasty (1368-1644 CE) and then the Qing dynasty (1644-1912 CE), and it was during these dynasties that the mooncake became intertwined with Chinese cultural practices, including the Mid-Autumn Festival and family reunion. This project will attempt to understand this evolution of the mooncake by attempting the recreation of three different mooncakes, one using a recipe from the Southern Song dynasty, one using a recipe from the Qing dynasty, and one modern recipe for mooncakes.

Southern Song Dynasty Mooncakes

Recreation of a Five Fragrance Cake

ChatGPT-generated image of the recipe for Five Fragrance Cake from a translation of Wushi Zhongkuilu (吳氏中饋錄) in Madame Wu’s Handbook on Home-Cooking: The Song Dynasty Classic on Domestic Cuisine by Sean J.S. Chen (Madame Wu).

Reflection

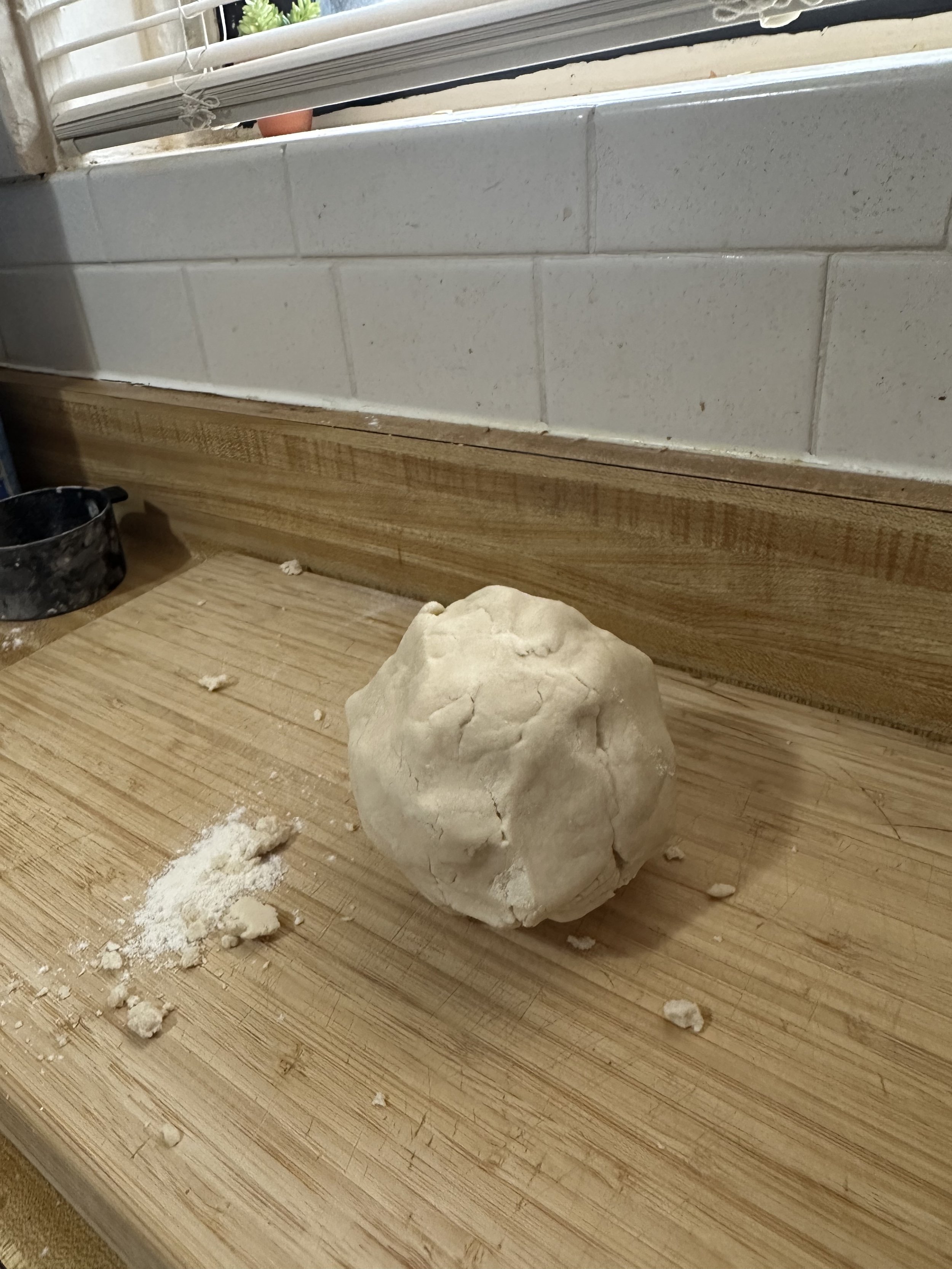

In reflecting on my attempt at creating the Five Fragrance Cake from the Southern Song dynasty, I realized that I encountered many more challenges along the way than expected. The first challenge was with acquiring ingredients. I couldn’t find the Japonica rice and decided to forgo the ingredient and just use the glutinous rice flour as the flour base. When making the dough, the dough felt very sticky and was difficult to work with. I wonder if the ground rice would have helped with the dough consistency. Aside from the glutinous rice flour and Japonica, the other ingredients were difficult to find and acquire at a reasonable price. I spend around 2 hours wandering the aisles of Olive Supermarket, looking for all of the ingredients. This was made difficult by there being several names for each ingredient meaning that I was just constantly checking for different names. I ended up finding two herb mixes that had the needed ingredients. I ended up improvising for the ginseng and getting tea bags made from 100% American ginseng, which probably wasn’t the ginseng that the recipe referred to, but it was the closest replacement that I could find. The next challenge I encountered was with grinding up the ingredients. As I lacked a mortar and a pestle, I tried to grind everything under a mug. This was relatively effective for the fox nut lily seeds, but didn’t work for the other ingredients. I tried using a food processor, but the ingredients were very hard and couldn’t even be broken up by the food processor. So I decided to put the ingredients in boiling water, in hopes that they would be easier to break up after soaking. However, I found that after soaking, the ingredients were not any easier to break up. So, I used the water that the ingredients soaked in as a part of the dough in order to hopefully bring the flavors into the cakes. The next challenge that I encountered was with the amount of sugar and water to add. The recipe just says to add sugar in boiling water, but not how much sugar in how much water. The next challenge that I encountered was with how long to steam the dough. I chose to steam the cakes for around 20 minutes. Although I am not sure what the cakes were supposed to be like, I don’t consider the outcome of recreating these Five Fragrance Cakes to be much of a success, with the consistency being difficult to eat and there not being much flavor. I think that these issues might have been fixed by using the Japonica rice and adding more sugar to the boiling water.

Discussion of Mooncakes During the Song Dynasty

The earliest surviving mention of the modern term “mooncake” (月饼) comes from 《梦粱录》 (Mèng Liáng Lù), which is translated as Dreams of Splendor of the Eastern Capital. This text is a 13th-century text written by Wu Zimu (吴自牧) during the Southern Song dynasty and it provides one of the most vivid and detailed accounts of urban life in Lin’an (modern-day Hangzhou), the capital city of the Southern Song. Even though the term “月饼” is mentioned in this text, no description is given for the pastry as it is just listed as one of the pasties that could be found among the vibrant street food in Lin’an, among which includes other pastries such as lotus leaf cakes (荷叶饼), hibiscus cakes (芙蓉饼), chrysanthemum cakes (菊花饼), plum blossom cakes (梅花饼), and many more (“夢粱錄). As this source, and other sources from the time period, don’t describe the specifics of these mooncakes, this recreation will focus on a similar recipe from the time period, keeping in mind the culinary practices from the Southern Song dynasty. The recipe chosen to recreate is the recipe for a Five Fragrance Cake, obtained from a translation of Wushi Zhongkuilu (吳氏中饋錄) in Madame Wu’s Handbook on Home-Cooking: The Song Dynasty Classic on Domestic Cuisine by Sean J.S. Chen (Madame Wu). Very little is known about what mooncakes were like during the Song dynasty, with most surviving mentions of mooncakes from surviving texts just mentioning the name and not describing what they looked like or how they were made. Based on descriptions of the culinary climate of the Southern Song dynasty, this recipe for Five Fragrance Cake seems to be a good representation of pastry items during the period and could possibly have been similar to a Song dynasty mooncake.

The Southern Song dynasty was formed of refugees fleeing south, and this was reflected in its capital, Lin’an, being described as the center of a commercial and social renaissance that included a new and cosmopolitan gastronomic culture, with life in Lin’an revolving around pleasure, glittering entertainment, and dining. From the mixed beginnings of this Southern Song dynasty, Hangzhou developed its own distinct culinary fashions, blending the northern heritage of noodles and cakes with the diverse seafood and abundant produce of the south (DuBois). This blending of cake culture brought from the north with dominant staples of the south is a major reason why the Five Fragrance Cake was chosen to represent Song dynasty mooncakes, as this cake uses rice flour as a base. Due to climate differences between the northern and southern parts of the region, rice was the predominant grain staple of the south while wheat dominated the north (Asia for Educators). As the Southern Song dynasty was formed from the loss of control over the northern half of the Song dynasty territory to the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty, the Southern Song dynasty, and its capital Lin’an, occupied this southern area where rice was the predominant grain staple. This blending of the refugees’ northern practice of cake-making with the southern emphasis on rice in the Southern Song dynasty could have led to a popular culture of pastries made using rice flour, like the Five Fragrance Cake. This assumption is further bolstered by the importance of rice further flourishing during the Southern Song dynasty due to increased reliance on rice for cuisine (Newman). This was in part due to a new variety of early-ripening rice that was introduced into China from Champa, a kingdom located in what is now Vietnam. This rice variety was more drought-resistant and ripened even faster than the other early-ripening varieties already grown in China at the time, allowing for the practice of double-cropping that vastly increased the availability of rice during the Southern Song dynasty (Asia for Educators).

Based on the mentions of mooncakes coming from contexts of street vendors and restaurant food, it can be inferred that mooncakes served the role of a snack or dessert, but that they likely weren’t connected to any larger celebrations or significance. The increased focus on maritime trade during this Song dynasty led to an increased quantity and availability of different foods, meaning that the rich and poor had access to more kinds of foods. This resulted in snacks becoming a more popular choice during these days, with many kinds available for purchase, particularly during night markets (Newman). The lack of description of the function of mooncakes during the time makes it difficult to determine the role that mooncakes played in Southern Song society, but the lack of description in surviving texts on ritual and society during the time suggests that mooncakes had yet to rise to cultural prominence, simply serving as a common snack or dish. This lack of description also means that the appearance of the mooncakes at the time is unknown. Since this appearance is unknown, a non-distinct bun shape was used for the shape of the recreation. Among surviving Song dynasty artifacts is a pastry mold in the shape of a peony flower (Li), indicating a possible popularity of flower motifs in pastry design, which is why a simple flower stamp was used in the recreation.

Qing Dynasty Mooncakes

Recreation of Lace-Patterned Mooncake

ChatGPT-generated image of the Lace-Patterned Mooncake recipe from Yuan Mei’s Recipes from the Garden of Contentment

Reflection

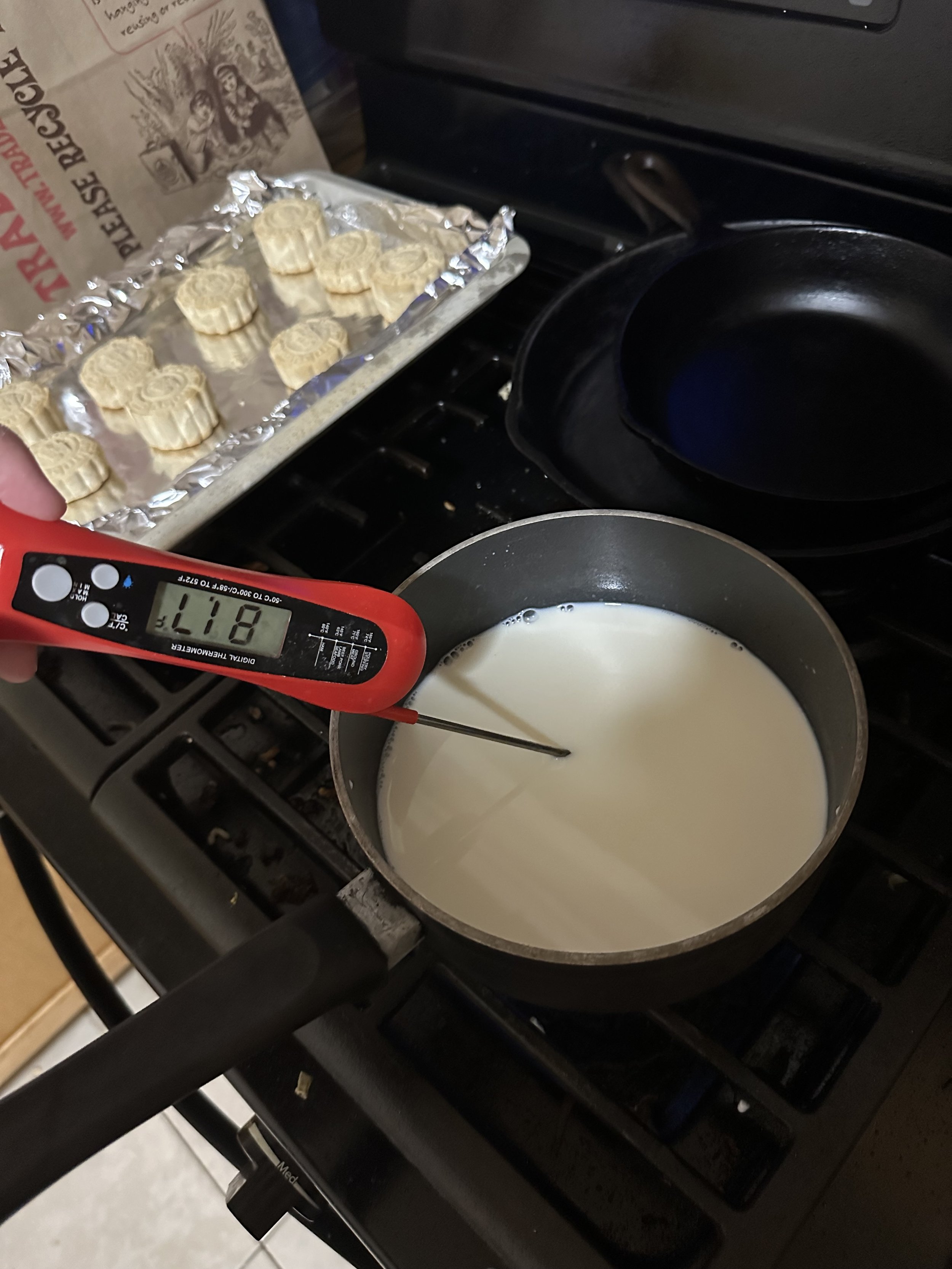

In reflecting on my attempt at recreating the Lace-Patterned Mooncake, I found this attempt to also not be a success. This recipe seemed very simple initially, but I realized that my biggest issue was with the amount of lard and flour to add. As there are no descriptions for the amounts of ingredients, I just guessed for the amounts of each to add by adding 2 cups of all-purpose flour and then adding lard until the consistency was able to be kneaded. I also was unsure how much the dough should be kneaded, but as the recipe said that more kneading would lead to a better dough, I ended up kneading the dough for roughly 25 minutes. Then it was time to add the jujube. When looking for jujubes, I couldn’t find fresh ones like the recipe called for, so I decided to use the candied version of the jujubes instead of the other dried jujube option as I hoped that they would be a bit more moist. Lastly, the recipe called for the mooncakes to be cooked in a firepot, which I don’t have. I figured that a Dutch oven would be the next best option, but I didn’t have one of those either. So, I decided to just try cooking them in the oven. I also didn’t know how long to keep the mooncakes in the oven, so I tried to just keep monitoring them every 5 minutes until they looked golden brown on top. After 20 minutes, I realized that they weren’t going to brown too much on top and quickly took them out. The resulting mooncakes were incredibly dry, almost to the point of being inedible, almost like a mixture of sand and sawdust that could hold its shape. I think that this result could have been improved by adding more lard and cooking for less time.

Discussion

After the fall of the Southern Song dynasty came the Yuan dynasty, where mooncakes were still present but still weren’t very prominent. It was only until the Ming and Qing dynasties that mooncakes, and the craft of mooncake making, rose to prominence, allowing for the modern mooncake style, with flaky crusts and diverse fillings, to take shape (Mao). In addition to the craft composition changing, mooncakes experienced significant transitions during the Qing dynasty that shaped their role and symbolism in Chinese culture. One important aspect of this transition is the consolidation of mooncakes as an essential part of the Mid-Autumn festival (中秋节). Mooncakes became increasingly popular during this time, among both the rich and poor. The festival itself gained prominence as a time for families to reunite and offer prayers to the moon. These mooncakes came to symbolize unity, harmony, and good fortune, becoming an integral component of Mid-Autumn festival rituals (“A Brief History of Mooncakes). From ancient times, many have regarded the full moon as a projection of completeness and unity, drawing people and things closer to a center. This symbolism ties in with the festival practice of communities and families returning to a center as relatives return from all over in anticipation of the Mid-Autumn Festival (Liu).

The Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties saw successful land expansions that pushed the northern boundary of China further and further north compared to where the border was during the Southern Song dynasty. Thus, the Qing dynasty had a wider variety of farmland and better access to areas for wheat cultivation in the north. This wider variety likely led to mooncakes being mainly made with wheat flour in the Ming and Qing dynasties when the mooncake became more popularized. The recipe chosen for the recreation of a Qing dynasty mooncake in the Lace-Patterned Mooncake reflects this preference for wheat flour. This is not to say that rice flour pastries were completely phased out during the period. Rice flour pastries were still present, as shown by different pastries in Yuan Mei’s Recipes from the Garden of Contentment also including rice flour pastries, such as snowy steamed cakes (Yuan). Although there are recipes for rice flour pastries, the number of wheat flour recipes still outnumber the rice flour recipes.

During the Qing dynasty, the geographical diversity of the land controlled by the Qing dynasty also correlated with the diverse growth of regional identities within the dynasty. These diverse regional identities were also reflected in their evolving and diversifying mooncake crafts. A variety of regions developed their own unique variations on mooncakes, each showcasing distinctive flavors, shapes, and fillings. An example of this were the Cantonese-style mooncakes that were popular in Guangdong Province and were characterized by their crisp golden crust and sweet lotus seed paste filling. In contrast, Suzhou-style mooncakes from Jiangsu Province often featured a flaky pastry shell wrapped around a variety of sweet or savory fillings (“A Brief History of Mooncakes).

Along with this emergence of new recipes and styles of making mooncakes came new popular ways of decorating mooncakes. Mooncakes had taken on a definite round shape to represent the moon that they were named after, and also to symbolize family reunion. In addition to the appearance becoming a standardized round shape, this Qing dynasty period marked increased intricacy in the designs that were stamped or molded on top of the mooncake. Intricate patterns were often imprinted onto the mooncake surface using special molds or hand-carving techniques, with these designs ranging from auspicious symbols (such as the moon, flowers, or mythical creatures) to intricate scenes depicting folklore and historical events (“A Brief History of Mooncakes). This Lace-Patterned Mooncake fits this description well, as although the recipe doesn’t describe a specific design to be used, the lace-patterned descriptor for the mooncake describes the intricate patterning designs embossed on top of the mooncake that resembles the complex patterning in lace work.

Modern Mooncakes

Recreation of Snow Skin Mooncake

Reflection

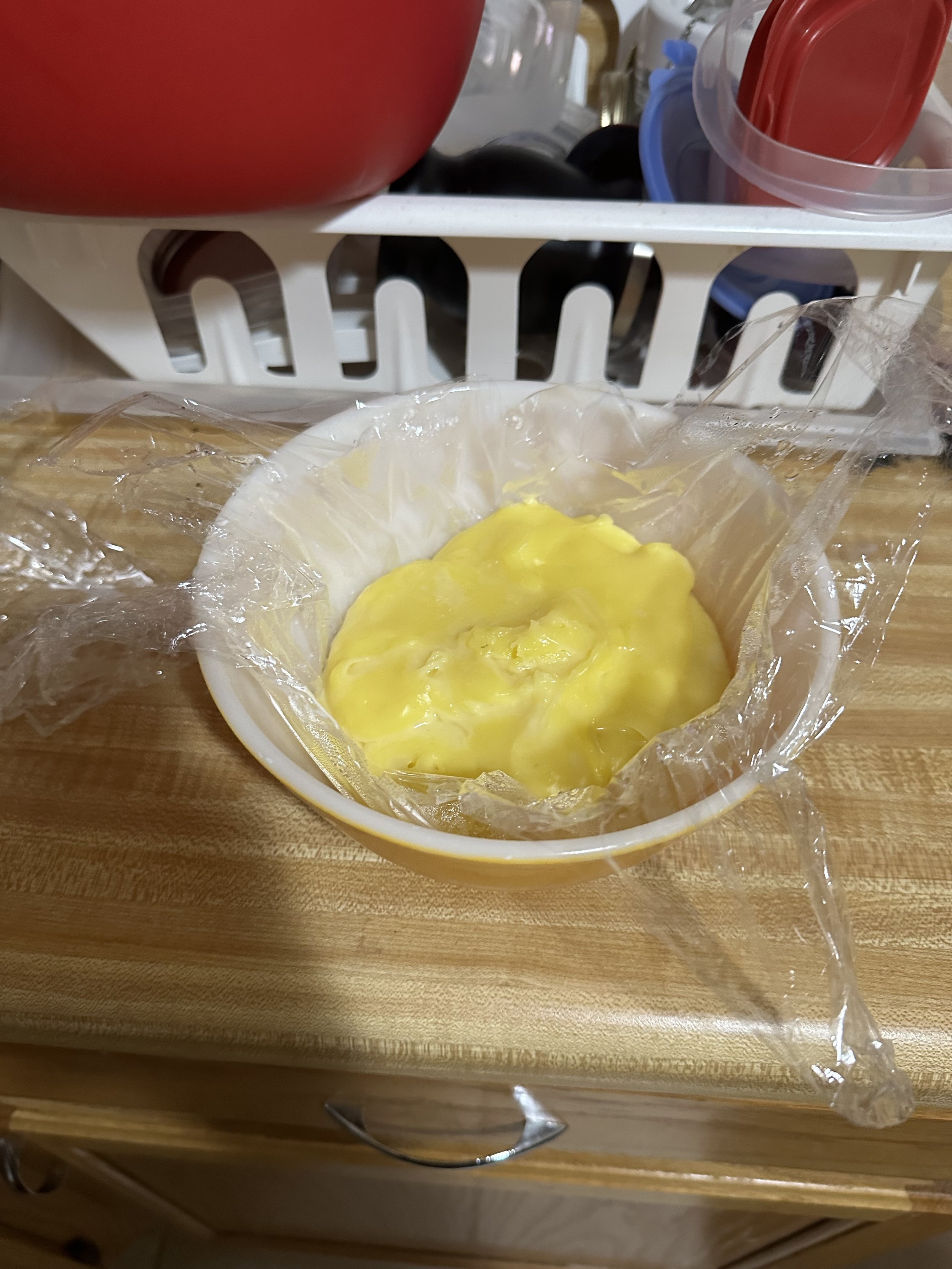

This mooncake finally succeeded! All of the ingredients for this mooncake were easily available, and the instructions for making the dough and filling were very detailed. This mooncake was several times for challenging and technical to make than the previous two, but the result came out much better. I feel that this experience highlights the importance of clear measurements, accessibility of ingredients, and detailed cooking instructions.

Discussion

Throughout the vast history of China, the mooncake craft has continued to evolve, continuously increasing in complexity of both symbolism and ritual. In contemporary times, mooncakes remain a central symbol of the Mid-Autumn Festival, a deeply valued celebration that has become central to Chinese culture and has spread across various parts of East and Southeast Asia. The festival not only signifies the close of the autumn harvest but also serves as a heartfelt occasion for families to reunite, express gratitude, and offer wishes for happiness and prosperity. The custom of exchanging mooncakes has been lovingly preserved through generations, representing unity, harmony, and the strengthening of personal bonds. Celebrating the Mid-Autumn Festival today often means gathering with family and friends under a luminous night sky, whether in parks or outdoor spaces aglow with lanterns. Children parade with colorful paper lanterns, dragon dances animate the atmosphere, and people come together to savor mooncakes while basking in the beauty of the full moon (“A Brief History of Mooncakes). Over time, the modest mooncake once sold in a simple brown paper bag has evolved into a significant symbol of both familial duty and business etiquette (Bedford). According to a survey conducted during the 2015 Mid-Autumn Festival, 63% of consumers chose mooncakes as festival gifts for their friends and family as well as their company colleagues (Cui). Despite the criticism, mooncakes have been symbolic of Chinese history. People—especially children—are naturally drawn to stories from the past, driven by an innate curiosity about their heritage, identity, and role within society. The tradition of making, buying, and sharing mooncakes plays a meaningful role in experiential learning, offering children an enjoyable, hands-on way to engage with the myths, legends, and cultural origins tied to the Mid-Autumn Festival. Through these festive activities, they informally absorb the rich history and symbolism behind the celebration, all while having fun (Bedford). Furthermore, mooncakes have been reflective of the globalization, rapid urbanization, and remarkable economic growth that China has experienced. The transformation of the mooncake serves as a reflection of these broader societal shifts. Once a labor-intensive delicacy that could take up to four weeks to prepare, mooncakes are now mass-produced thanks to automation (Bedford).

In terms of the ingredient composition of the craft, classic ingredients like lotus seed paste and salted duck egg yolks are still widely cherished, but the culinary landscape has expanded to serve all variety of tastes and to embrace contemporary palates. Flavors such as caviar, strawberry cream cheese with Oreo crumble, black truffle, and durian snow skin filled with custard and salted egg cream have added a bold, modern twist to this time-honored treat (“A Brief History of Mooncakes). During the Qing dynasty, there were many regional varieties of mooncakes, a landscape that is similar to the modern situation. Regional styles of mooncakes in China often reflect the country’s diverse ethnic and cultural landscapes, with distinct differences in both flavor and presentation. The tools used to "stamp" or imprint decorative patterns onto the mooncake’s crust also vary from region to region, reflecting local aesthetics and traditions. Many of these regional mooncake styles draw inspiration from the area’s native cuisine. For instance, the widely loved sweetened lotus seed paste filling is often enhanced with local flavor accents—orange peel is commonly added in the Guangzhou region, while rose and peach blossom extracts are favored in Hong Kong. In Shanghai, fillings take a more inventive turn, incorporating ingredients such as pork, walnuts, salted chicken egg yolk, and even sweetened giblets, offering a savory twist to the traditional mooncake (Liu).

In modern mooncake-making craft, presentation has become paramount. The surfaces of mooncakes are elaborately adorned in a variety of patterns, generally bountiful with traditional Chinese motifs of happiness, prosperity, longevity, luck, and prosperity (Liu). Modern varieties of mooncakes have also diversified to attract wider ranges of consumers. For certain variations, fillings enhanced with colorful and tasty ingredients are used, whilst others are packaged more creatively, such as the Kung Fu Panda 3 series, taking advantage of the mooncake body to convey a popular and modern image to attract a new generation of consumers (Liu). In recent years, luxury brands have also entered the scene, crafting their own signature mooncakes to cater to elite clientele. These premium offerings are often housed in opulent packaging embellished with intricate, artful designs—creating a multisensory experience that blends taste with aesthetic allure (“A Brief History of Mooncakes).

Although the significance of mooncakes in Chinese culture has only increased, there have been criticisms levied at the mooncake craft. Although the cultural importance of the mooncake has not diminished, the increase in materiality of the mooncake craft has meant that its symbolic significance and spiritual meaning are becoming weaker. In contrast, the increasing strength of the material value of the mooncake is mainly reflected in the excessive packaging of this festival food (Cui). The primary role of packaging is to protect products during transport and to help market them. However, excessive packaging goes beyond this purpose, adding unnecessary features and inflated value. This is often seen in overly complex structures, excessive decorative elements, and the use of materials that are difficult to recycle or impractical. It also leads to high costs and overdesign. Ideally, packaging should complement the product without overshadowing it. Excessive packaging, however, prioritizes commercial appeal over function, losing sight of packaging’s true purpose. In contrast, well-balanced packaging supports product protection, enhances sales, and conserves environmental resources (Cui). Another criticism of the modern mooncake culture addresses their function as gifts. Modern mooncakes function as lavishly packaged mooncakes that are exchanged among families, friends, colleagues, and business partners, often as part of grander gestures. In some cases, these cakes are accompanied by extravagant gifts that far surpass the value of the mooncakes themselves, prompting criticism that such offerings amount to a sophisticated form of bribery (Bedford).Conclusion

Through the recreation of mooncakes from the Southern Song dynasty, Qing dynasty, and modern times, I have come to understand how this iconic pastry serves as a lens into the evolving culture, values, and culinary traditions of Chinese society. In the Southern Song period, mooncakes appear as simple, everyday snacks with minimal cultural or ritual significance—reflected in my recreation of the Five Fragrance Cake, which emphasized local ingredients and the emerging blend of northern and southern food cultures. By the Qing dynasty, mooncakes had transformed into symbolic, celebratory treats deeply tied to the Mid-Autumn Festival, embodying themes of family unity and regional identity, as shown in the intricate design and wheat-based recipe of the Lace-Patterned Mooncake. Finally, my recreation of a modern mooncake revealed the globalized, commercialized, and increasingly diverse landscape of mooncake production today—where traditional symbolism persists even as innovation, luxury branding, and mass production redefine the craft.

Each recreation not only illuminated the culinary techniques of its time but also demonstrated the broader cultural values and societal shifts of each era. The mooncake has evolved from a simple snack into a rich cultural symbol—one that continues to connect people to their heritage, their families, and to each other. Through making these mooncakes, I gained a deeper appreciation for how food can preserve history, shape identity, and adapt to reflect the changing values of society across centuries.

Works Cited

1. Cui, J. (2019). Mooncake packaging design: an exploration of Mid-Autumn Festival symbolism and minimalist design: a thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master in Design at Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand (Doctoral dissertation, Massey University). https://mro.massey.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/0ac233f6-56f7-481a-9fbe-a0c16d50b753/content

2. “夢粱錄 : 卷十六 - 中國哲學書電子化計劃.” Chinese Text Project, ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=863405&remap=gb. Accessed 15 Apr. 2025.

3. DuBois, Thomas. “Jiangnan Cuisine: How the Ancient Literati Wrote about It [Eye on Jiangzhehu Series].” ThinkChina, Think China, 24 Jan. 2025, www.thinkchina.sg/culture/jiangnan-cuisine-how-ancient-literati-wrote-about-it-eye-jiangzhehu-series.

4. Madame Wu, Chen, S. J.S., Anderson, E. N., & Brown, M. (2023). Madame Wu’s Handbook on Home-cooking: The Song Dynasty Classic on Domestic Cuisine. Linea.

5. Asia for Educators, Columbia University. “China in 1000 CE: Technological Advances during the Song.” Song Dynasty China | Asia for Educators, afe.easia.columbia.edu/songdynasty-module/tech-rice.html. Accessed 19 Apr. 2025.

6. Newman, Jacqueline. “Song Dynasty and Its Foods.” Flavor and Fortune, Institute for the Advancement of the Science and Art of Chinese Cuisine, 2008, www.flavorandfortune.com/ffdataaccess/article.php?ID=678.

7. Li, Yingxue. “New Book Sheds Light on Chinese Pastries’ Rich History.” Chinadaily.Com.Cn, 24 Aug. 2018, www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201808/24/WS5b7f4a55a310add14f387806.html.

8. Yuan, Mei. Recipes from the Garden of Contentment: Yuan Mei's Manual of Gastronomy, edited by J. S. Chen Sean, Berkshire Publishing Group, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/wustl/detail.action?docID=5987991.

9. Liu, Ann. “Exploring the History of Mooncakes: A Cultural Journey.” Medium, Medium, 20 July 2024, medium.com/%40yuebeiliu/exploring-the-history-of-mooncakes-a-cultural-journey-3c3c9879e5a9.

10. Mao, Jeff. “Exploring the Rich History of the Mid-Autumn Festival and Mooncakes.” Knead & Nosh, 25 Aug. 2023, kneadandnosh.com/article/2023/08/exploring-the-rich-history-of-the-mid-autumn-festival-and-mooncakes/.

11. “A Brief History of Mooncakes: The Sweet Story Behind the Festival Treat.” Food For Foodies, Food For Foodies, 3 Aug. 2023, www.foodforfoodies.co.uk/blogs/mooncakes/a-brief-history-of-mooncakes-the-sweet-story-behind-the-festival-treat.

12. Bedford, E. (2011). Mooncakes and the Chinese Mid-Autumn Festival: a Matter of Habitus. In Asian Material Culture(pp. 19–38). essay, Amsterdam University Press