Satsuma-imo: Recreating Japanese Sweet Potato Recipes

These are murasaki-imo (beni-imo). They are the most popular Japanese sweet potato, the type which I used for this project.

Background - Sweet Potato Origin

Satsuma region (red), within the Kagoshima Prefecture (shaded dark blue)

The Japanese sweet potato first entered Japan in the late Muromachi period, during a “culinary revolution” called Namban Ryori. During this time, lots of Spanish, Portuguese, and generally southern ingredients were brought into Japan. Sweet potatoes were mainly ignored at this point, and they weren’t truly acknowledged until the 17th century.

In the late 17th century, a Japanese farmer named Maeda Riuemon visited the Chinese coastal town of Luchu. He discovered the unfamiliar sweet potato, and brought it home to the Southern Japanese region of Satsuma, in the Kagoshima prefecture. [1]

The Japanese sweet potato first appeared in Japan in the Satsuma region, hence its Japanese name “satsuma-imo”.

Background - Cultural Breakdown

The satsuma-imo spread throughout Edo Japan for various reasons, some of which can provide us with a better understanding of Japanese culture at the time.

Famine:

The sweet potatoes were first embraced by the Satsuma region in Kagoshima prefecture. Kagoshima was an area which was infamous for food shortages at the time. Rough topography, volcanic soil, and unpredictable terrain embodied the southern prefecture, inhibiting the growth of various basic crops and grains. [2] Even rice, one of the most abundant crops in Japan, had difficulty growing there. Sweet potatoes were different. They were easy to grow and cultivate, requiring minimal effort for a harvest. Sweet potatoes provided the region with a steady food supply, which was somewhat of a rarity for Edo Period Japan.

Despite being easy to cultivate year round, other regions of Japan were less willing to accept the crop. It became stigmatized as a “cheap farmers’ food”; a food meant only for rural, lower status citizens. [3]

Around the year of 1732, the Kyoho Famine struck, taking countless lives. The years were filled with perilous weather and a major rice shortage, leading to starvation. In response to this wave of starvation, a scholar named Aoki Konyo began to cultivate sweet potatoes from the satsuma region in Edo, the capital city of Japan. He studied and bred the sweet potatoes, hoping to provide a new, reliable source of nutrients for the Japanese people. His efforts resulted in a rapid rise in sweet potato cultivation in Japan’s capital city, and the surrounding Kanto region. Sweet potatoes are a self-sufficient crop, and they were used as a substitute staple food during food shortages. Konyo’s work led to the proliferation of sweet potatoes throughout Japan. In the modern day, he is referred to by many as Kansho Sensei, or “Mr. Sweet Potato”. [4]

Lower Status - A Daily Driver

Illustration of a yaki-imo vendor during winter (left side of the image is his vending station) [6]

Sweet potatoes were in widespread use as the Edo Period progressed, but they were mainly consumed by peasantry, youths, and low level samurai. Sweet potatoes were cheap, abundant, and easy to cook. They were used by the poor as a source of sustenance. Street vendors emerged throughout the nation – especially in rural areas – offering a variety of inexpensive, classic sweet potato dishes such as yaki-imo (baked sweet potato), mushi-imo (steamed sweet potato), and fire roasted sweet potato. [5] Yaki-imo was by far the most popular, and it provided Japanese with nutrition and warmth during the winter months.

The Development of Meal Etiquette – The Ceremonial Sweet Potato

Towards the late Edo Period, sweet potatoes adapted a new form. Their sweet, creamy flavor could be combined with other ingredients for ceremonial dishes and desserts. Around this time, food etiquette and formalized meal plans were becoming significant in the upper echelons of Edo Japan. As rulebooks and manuals came out directing elites on what to eat, many “superb” and “exquisite” sweet potato dishes emerged. Recipes such as tsukihi-imo, kabayaki-imo, and fluffy sweet potato could be found in various elite-level banquets, such as weddings and ceremonial meetings. [7] These dishes were rarely eaten by working status Japanese citizens.

Recreation - Cooking Various Dishes

Yaki-imo (baked sweet potato)

Baked sweet potatoes were so common in lower status culture by the mid-Edo period that most recipe books don’t even provide a recipe, just the name of the dish. The rest is expected to be previously learned by the maker. I used certain guidelines to determine how to approach this recipe.

Guidelines:

1. Finding potatoes: I needed murasaki (beni-imo) potatoes, and I found them at Trader Joes.

2. Washing the skin: Since the majority of yaki-imo are prepared with the skin on, I decided to wash the skin thoroughly.

3. Baking/cooking: I based my cooking times off of previous learned tacit knowledge regarding regular baked potatoes.

Cooking

I cooked the Yaki-imo in two ways, one representing traditional lower status methods and one representing methods most likely used during famine. The grill I used is similar in nature to a raised kamado, a grill commonly used in Edo Japan, and most likely used during famine. I then removed the grate from the grill in order to bake the sweet potatoes directly in the fire, in order to represent lower status cooking. Japanese street vendors used stone ovens to cook their potatoes, helping to enhance the sweetness and aroma of the dish.

Image of a yaki-imo vendor using a traditional stone oven [8]

Example of a raised kamado [9]

Method 1: I placed the murasaki-imo on a charcoal grill, which replicates a raised kamado. This method resulted in an evenly cooked, warm sweet potato.

Method 2: Cooking within both charcoal and hot stones, to replicate the stone ovens used by street vendors. This method resulted in a smokier tasting final product.

Ceremonial Dishes: Tsukihi-imo, Kabayaki-imo, Fluffy Sweet Potato [10]

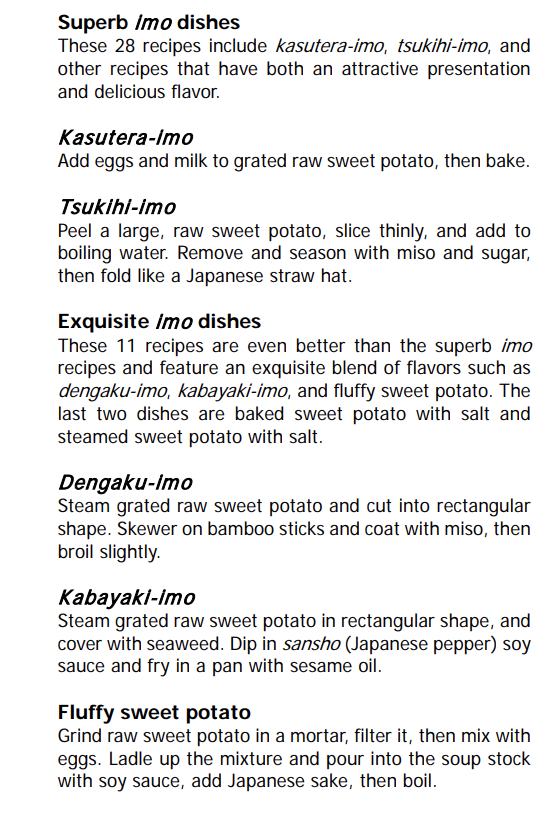

The following recipes were based on the novel Imo Hyakuchin, by Hiranoya Hanemon. The novel was created in the mid-Edo Period, and it breaks down over 100 recipes centered around sweet potato.

These two images are from a secondary source which summarizes Imo Hyakuchin, written by Yasuyo Nagamura [11]

Tsukihi-imo

Ingredients:

-raw Japanese sweet potato (peeled)

-miso

-sugar

Recipe:

-Peel a large, raw sweet potato

-Slice thinly

-Add to boiling water

-Remove and season with miso and sugar, then fold like a “Japanese straw hat”

This recipe was difficult to put together. I could not successfully fold each piece of sweet potato as the recipe suggested. In order to adapt, I used small pieces of sweet potato and miso to create the shape of a straw hat. It tasted both salty and sweet, and reminded me of a tea snack or dessert.

Kabayaki-imo

Recipe:

-Peel and cut a raw sweet potato into rectangular -shapes

-Cover with seaweed

-Dip in soy sauce mixed with sansho pepper

-Add sesame oil, and fry in a pan until crispy

Ingredients:

-raw Japanese sweet potato, peeled

-seaweed

-sansho pepper

-soy sauce

-sesame oil

Finished product! It was delicious!

Although this recipe went surprisingly well, there were a lot of moments where things could have gone wrong. Wrapping, shaping, frying, and skewering the sweet potatoes proved to be a very difficult and tedious process.

Fluffy Sweet Potato

Recipe:

-grind raw sweet potato with mortar and pestle

-mix with eggs

-pour mixture into soup stock and boil

-top with seasoning (furikake)

Ingredients:

-raw Japanese sweet potato

-eggs

-soup stock/chicken stock

-soy sauce

-Japanese sake

Finished product! It was really warm and tasty!

This recipe was incredibly fun to prepare, although it was very complicated. The recipe I based it off of did not elaborate on how to “grind” the sweet potato, so I grated it first before using a mortar and pestle. The recipe provided no information on how to boil the dish, so I had to improvise.

Reflection

During my recreation, I noticed that the recipes meant for famine and lower status individuals were far more simple and basic than the recipes for ceremonial and banquet use. The yaki-imo recipe required very little textual knowledge, and it called for only one ingredient. Besides tending to the fire, I had no trouble. Through my recreation, I was able to understand why the sweet potato emerged in popularity in the early Edo Period: in order to address both famine and poverty within the nation. They were simple and versatile in nature, allowing for easy access and consumption.

The ceremonial recipes for tsukihi-imo, kabayaki-imo, and fluffy sweet potato were far more intricate and complicated. As I was cooking, I realized the large amount of complex ingredients and instructions required for completion. Although I was able to somewhat complete each dish, I lacked certain skills that I’m sure I would have needed in order to replicate the dish to its most accurate form. Regarding the tsukihi-imo, I had trouble folding the potatoes into a “straw-hat” shape. I was unable to recreate it accurately due to the complexity of the meal. I ran into similar issues with my other recipes. I had to improvise on the spot, try new things, and test new flavors. While struggling to complete each dish, it became clear to me that these recipes were meant for specified events and elitist environments. The flavors, tastes, and processes were far more complex than the yaki-imo recipe. Only the most knowledgeable chefs could have completed these dishes perfectly. They were not meant as typical, daily meals for lower status individuals.

Lesson Learned

The true way for one to understand a given crop or ingredient is to understand what that crop's use meant to a section of society. In order to find this out, I had to recreate various recipes in a historical nature. In the case of the sweet potato, I was able to learn that as the dish developed, lower status necessity was eliminated, and values of luxury and intricacy became most significant. As the sweet potato moved up the Japanese hierarchical ladder, it developed new forms and styles representative of the elite, upper class. It became extremely popular because each social class within Japan was able to find a use for it.

In closing, an item can become more popular and grow in relevance once each social class accepts its existence and adapts it for their own needs. A dish must fit the social context (famine, poverty, ceremony) of a given culture at a given time in order for it to proliferate fully within a country. Once that item serves an important use for a groups’ social and cultural values, it has reason to be incorporated into life and expanded upon.

Works Cited:

[1] Cooley, J. S. “Origin of the Sweet Potato and Primitive Storage Practices.” The Scientific Monthly 72, no. 5 (1951):

325–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20102.

[2] Woolfe, Jennifer A. 1992. Sweet Potato : An Untapped Food Resource. Cambridge [England] ; New York :

Cambridge University Press. http://archive.org/details/sweetpotatountap0000wool.

[3] Rath, Eric C. 2017. “Historical Reflections on Culinary Globalization in East Asia.” Gastronomica 17 (3): 82–84.

https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2017.17.3.82.

[4] Inc, NetAdvance. n.d. “【本文表示】.” JapanKnowledge. Accessed December 4, 2021.

http://japanknowledge.com/lib/display/?lid=1001000010473.

Nagamura, Yasuyo. 2019. Imo Hyakuchin: Sweet Potato Dishes of the Edo Period - 国立国会図書館デジタルコレ

クション. Vol. 225. Japan: National Diet Library newsletter. https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/11481319.

[5] Woolfe, Jennifer A. 1992. Sweet Potato : An Untapped Food Resource. Cambridge [England] ; New York :

Cambridge University Press. http://archive.org/details/sweetpotatountap0000wool.

[6] Nagamura, Yasuyo. 2019. Imo Hyakuchin: Sweet Potato Dishes of the Edo Period - 国立国会図書館デジタルコレ

クション. Vol. 225. Japan: National Diet Library newsletter. https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/11481319.

[7] Assmann, Stephanie and Eric C. Rath. 2010. Japanese Foodways, Past and Present.

[8] Hanemon, Hiranoya. n.d. “Imo Hyakuchin (甘藷百珍) - NDL Digital Collections.” National Diet Library Digital

Collections. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/2536724?__lang=en.

[9] “The Word Kamado -- Naked Whiz Ceramic Charcoal Cooking.” n.d. Accessed December 8, 2021.

http://www.nakedwhiz.com/kamadotheword/kamadotheword.htm.

[10] Hanemon, Hiranoya. n.d. “Imo Hyakuchin (甘藷百珍) - NDL Digital Collections.” National Diet Library Digital

Collections. Accessed December 8, 2021. https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/2536724?__lang=en.

Assmann, Stephanie and Eric C. Rath. 2010. Japanese Foodways, Past and Present.

[11] Nagamura, Yasuyo. 2019. Imo Hyakuchin: Sweet Potato Dishes of the Edo Period - 国立国会図書館デジタルコレ

クション. Vol. 225. Japan: National Diet Library newsletter. https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/11481319.