Sickly Sweet: Recreating Lady Yi’s Yakgwa

How Yakgwa epitomizes Joseon Korea’s view of food as medicine

What is Yakgwa?

Flour, Oil, and Honey

This is all one needs to make yakgwa, a traditional Korean confection. While yakgwa literally translates to “medicine cookie”, it is better described as a honey cookie. To make it, the dough made of flour, oil, and honey is pan-fried and then the resulting cookies are soaked in a honey syrup. Yakgwa’s popularity traces all the way to the Goryeo Dynasty (936-1392 CE) when grain cultivation and production increased due to the Buddhist regime discouraging the consumption of meat, but its origin potentially stretches to the Three-Kingdom Period (57 BC- 688 CE) (1). Yakgwa was typically enjoyed during festivals or other important events. They became so popular during the Goryeo Dynasty that it’s use was even restricted by King Myeongjong in 1192, who stated that “grains are wasted as if they were grains of sand” (2). Notably, the treat was primarily consumed by the upper classes due to the valuable ingredients it required (3). Honey, oil, and flour were all considered nutritional ingredients, explaining its literal name of a medicine cookie. Understanding why these ingredients were considered medicinal is something I aimed to explore in my project and will discuss later in this paper.

Lady Yi’s Yakgwa Recipe

Importantly, before the cooking directions even begin, Lady Yi points out the value in the ingredients as nutritional, providing explanations to each respectively. The inclusion of this prompts further questioning into why honey, flour, and oil were seen as healthy. It also raises one of my key questions:

How and why was food/diet viewed as medicine during the Joseon Dynasty?

Other questions I plan to explore:

What does Lady Yi’s position in society and her knowledge of culinary craft indicate about yakgwa’s significance?

What does this recipe reveal about Lady Yi’s motivations in writing this recipe?

What relation does this recipe have with previous culinary books written by men that focused emphasis on medicine? (as mentioned by Ro in "Cookbooks and Female Writers in Late Chosŏn Korea")

Filling in the Gaps

Before beginning the recreation process, I had to determine answers to some of the following questions:

What kind of flour is used?

How much flour is used?

What is jeupcheong? How do I make it? (measurements/proportions)

How much jeupcheong is needed?

What kind of oil do I use?

How much cinnamon powder, black pepper powder, dried ginger powder, ginger juice, and chopped pine nuts do I need?

For the flour, I debated whether to use all-purpose flour, rice flour, or a combination of both. I ultimately decided on all-purpose flour. While a combination seems to be more common today, one culinary article noted that “producing white wheat flour involved a long process of husking, removing the skin of wheat grains and then grinding the core into a fine powder” and “in pre-modern Korea, wheat was rarer than rice and other cereals” (4). All-purpose flour is closer to what was used in pre-modern times. Because white wheat flour was rarer and required more time to produce, it was assigned a higher value, making it more likely to be used in this elite dessert.

As for when to add it, I used my tacit baking knowledge to determine that it should added when I am making the dough. The question of how much to add is something I actively explored during the process.

Now, what is jeupcheong?

It is the soaking syrup needed to make yakgwa. I found answers to its ingredients in another Korean culinary book, Ŭmsik Timibang. The yakgwa recipe I translated is as follows:

“Yakgwa method: For one mal of flour put two (mal) of honey, five hop of oil, three hop of alcohol, and add three hop of boiled water and knead it softly, and then add 1 ½ hop of water to one doe of choch’eong to water it down and then apply [on the dough?]. ”

The key part is the “1 ½ hop of water to one doe of choch’eong… then apply”. This tells me that jeupcheong is made of water and jocheong. Jocheong, according to a quick google search, is rice syrup.

Ingredients & Measurements:

Before I could begin recreating Lady Yi’s recipe, I had to determine the ingredients and measurements I planned on using and do the calculations to proportionately scale down the recipe. The recipe’s output is 1 mal (18 Liters) of yakgwa. Thus, I decided to eighteenth the recipe. These are the ingredients and their measurements in the original recipe:

three toe (5.4 liters) of oil (total)

two toe (3.6 liters) of honey for the dough

three toe (5.4 liters) of honey (total)

one-half toe (0.9 liters) of oil for the dough

a lot of soaking syrup (cheupch’eong)

a little less than one small bowl (posigi) of soju

unknown measurements of

flour, soaking syrup, cinnamon powder, ginger powder, black pepper powder, ginger juice, pine nuts

One thing that confused me at first was the fact that two different measurements were given for the oil and honey: one just for the dough and one for the total used. That left extra oil and honey. At first, I was not sure where that was meant to go. Ultimately, I determined that the extra oil was meant for frying and the extra honey was meant to go into the jeupcheong along with water and jocheong.

Also, for the soju measurements, I could not find a modern-day conversion of a posigi so I referred back to the Ŭmsik Timibang recipe. It called for 3 hop of alcohol relative to 2 mal of honey and 1 mal of flour. I decided to use these proportions for my recipe and hope they matched up with the proportions in Lady Yi’s recipe. I consequently used the ratio of honey to flour here to determine how much flour I would need.

Calculations

-

1 Mal = 18 Liters = 76 cups

1 Toe = 1.8 Liters = 7.6 cups

1 Hop = 180mL = 0.76 cups

-

TOTAL OIL: 5.4 liters oil --> 0.3 liters oil = 1.27 cups oil

TOTAL HONEY: 5.4 liters honey --> 0.3 liters honey = 1.27 cups honey

HONEY FOR DOUGH: 3.6 liters honey --> 0.2 liters honey = 0.85 cups honey

OIL FOR DOUGH: 0.9 liters oil --> 0.05 liters oil = 0.21 cups oil

OIL FOR FRYING: 1.27cups – 0.21 cups = 1.06 cups oil

-

1 mal flour : 2 mal honey : 3 hop alcohol

18L flour : 32L honey : 0.54L soju

1L : 2L : 0.03L

4.23 cups flour : 8.45 cups honey : 0.13 cups soju (2.08 tablespoons)

Approx. 1 cup flour: 2 cups honey

Thus, 0.4255cups flour

-

1 doe jocheong = 1.8L --> 0.1L = 0.42 cups jocheong

1 ½ hop water = 270mL --> 15mL = 1 tablespoon water

1.27cups total honey - 0.85 cups honey for dough= 0.42 cups honey

Time to Bake

First, I prepared the soaking syrup (jeupcheong). I simply mixed the 0.42 cups honey, 0.42 cups rice syrup (jocheong), and 1 tablespoon of water together in a bowl. Lady Yi’s recipe noted that the soaking syrup was “mixed with cinnamon powder, black pepper powder, dried ginger powder, and ginger juice” (6). No measurements were provided so I just used my own intuition and tacit baking knowledge to guess. I went with 1 teaspoon of ginger juice (it smelled strong, and I didn’t want the flavor to be overpowering) and about a pinch/two shakes of each spice and mixed that in.

Next, the dough. Using my tacit knowledge of baking, I know that you are supposed to mix wet ingredients before adding dry ingredients. Thus, I first combined 0.85 cups honey, 0.21 cups oil, and 2.08 tablespoons soju in a bowl. Then I added the 0.4255 cups of flour that I had determined using the proportions from the Ŭmsik Timibang recipe. However, when I had finished mixing it in, the “dough” was still very liquid. I knew something was wrong, especially because Lady Yi’s recipe says the dough must be rolled out for it to be shaped. There was no way for this to be rolled out and it need more flour. Thus, I entered a highly experimental stage whereby I slowly added flour by the quarter cup and eventually by the teaspoon. I wanted to accurately track my measurements and make sure I didn’t add too much flour. It was a very tedious process. Eventually it started to become more dough-like and I was able to begin kneading it. Due to the fact that there was so much honey in the dough, it felt like I could add flour forever and it would continue to be sticky. I stopped adding flour after the total flour contributed was 2.616cups.

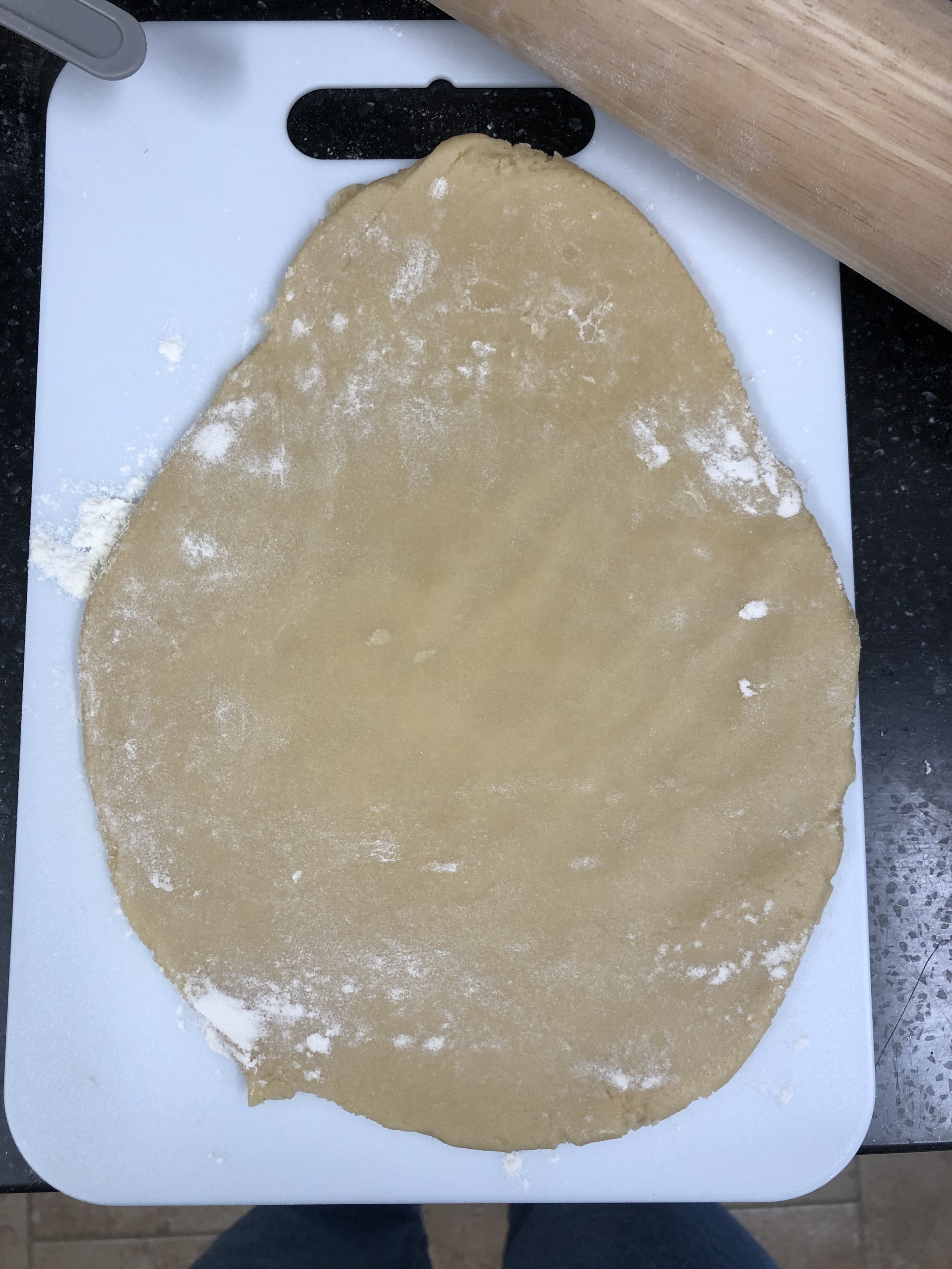

I rolled the dough out on a cutting board and cut it into squares (I later decided I didn’t like the squares and just rolled the dough into balls and then flattened them).

Now it was time to fry. I had decided to use canola oil (for this and the dough) since a quick Google search told me this was the most used baking oil, and it has little to no flavor. I put 1.06 cups of oil into a pan and began to heat it. Lady Yi’s recipe did not mention any temperature to fry at so I just had to experiment with high versus low versus medium temperatures and add bits of dough to see how it cooked. If the temperature was too high the outside would burn fast and the inside would not cook fully, but if it was too low it would just sit in the oil, not really cooking and just absorbing oil. I ended up cooking at a medium-low temperature. This allowed me to flip the yakgwa while it cooked a few times. Once the cookies turned golden-brown and the top began to crack a bit around the edges, I took it out and let the oil drain on a paper towel.

Here is where I messed up a bit. Rather than “drench[ing]” the yakgwa in soaking syrup, I just spooned a spoonful on top of each cookie and then let it dry in the air. The cookies still ended up tasting and looking good, but I think if I had properly soaked them in a bowl of syrup rather than just a spoonful the whole thing would have been moister.

Let’s Try it Again

I did not change a whole ton for Trial 2. For the soaking syrup, I did the same amount of honey, rice syrup, and water, but I used 1.5 teaspoons of ginger juice, about 2-3 shakes of ginger powder and pepper powder, and about 4-5 shakes of cinnamon powder. In Trial 1, I couldn’t really taste any of the spices so I wanted to try adding more for flavor.

For the dough, I used the same amount of honey, oil, and soju. I intended to use the 2.616 cups of flour I ended up at in Trial 1, but after 2 cups of flour the dough was not really absorbing the last 1/8 cups of flour. I decided not to add the last 9 teaspoons of flour and used the last bit of unincorporated flour to keep the dough not-sticky for when I was shaping it.

For frying, I again just had to mess about with the temperature to find the exact right one at around medium-low. I did have an issue getting the dough to stay together at first. I realized that the pieces I had formed were too thin and kept breaking, so I made sure they were thick enough and we were back to normal. After frying, I let the oil drain. Finally, rather than spooning on the syrup, I soaked around 6 yakgwa at a time in the bowl for about 10-20 minutes and then let them sit out for a bit. This time the entire thing was moister and there was a slight hint of cinnamon. Also, this batch made 17 yakgwa in total (not including the many failed frying attempts).

Reflection

During my recreation, the sheer volume of honey, oil, and flour I was working with felt substantial. These three ingredients were messy, and their presence was strongly felt—honey is sticky and viscous; oil is almost impossible to remove, seeming to leave behind a residue even when washed more than once; and flour goes absolutely everywhere. Even with a batch where I had 18thed the recipe, I felt like I was working with a ridiculous amount of honey, oil, and flour. Thus, I couldn’t help but reflect on the original recipe which produces 18 liters of yakgwa and requires 18 times the ingredients I used. This highlighted the fact that yakgwa were typically made for festivals and other large events. Perhaps working with these difficult ingredients was only worth it in the large capacity and for a special event. I would imagine that the effort that went into creating yakgwa on such a scale only heightened the prestige placed on it.

Additionally, as noted before in my prep work, much crucial information was left out of the recipe. Oil frying temperature, the spice measurements, and the amount of flour—all of this would have been tacit knowledge of the time. People making yakgwa would have known what the dough should look like before frying, thus not needing measurements for flour. Same goes for the spices, which perhaps would have been eyeballed and taste-tested for the known, proper taste, and the frying temperature, which would also have been tacit knowledge of the maker.

Rather than intending for readers to make this themselves, I believe that Lady Yi included this recipe because of its cultural importance as a food which embodied health. The lack of vital information in this recipe leads me to believe that this was not one of Lady Yi’s own recipes and she likely never made it herself. Also, the utter volume of yakgwacalled for in this recipe would only have been possible to produce in a kitchen of mass scale, like the royal kitchens. Thus, Lady Yi probably received this recipe from a kitchen staff member. Furthermore, in the preface of her encyclopedia, Lady Yi asserts that “the main gist of this book… is to attend to one’s health” (6). Not only is the makeup of the recipe not easily conducive to recreation by a single individual, but also Lady Yi begins the recipe by establishing the health benefits of yakgwa.

Why such an emphasis on health?

In pre-modern Korea, honey, oil, and flour were considered beneficial to one’s health. Lady Yi provides an explanation of these cultural beliefs, writing that “flour is a resource for the vital energy from the four seasons, honey is the best of the medicines, and oil kills insects and detoxifies” (6). This cultural understanding of honey, oil, and flour as nutritional, and even medicinal, explains yakgwa’s name as a medicine cookie. Working with honey, oil, and flour felt very involved, so I can imagine how the process of making yakgwa would contribute to an embodied feeling of connection to the medicinal qualities of these ingredients.

The cultural perception of food as medicine is grounded in the Confucian ideology that predominated pre-modern Korea. In the article “Science, Food and Health in Joseon Korea”, Michael Pettid explains how, in accordance with Confucian values of filial piety, “[a]s the body itself was bequeathed by one’s parents, it was to be taken care of as a sign of respect… Thus, eating correctly and preventing illness was as important as serving one’s parents” (7). Filial piety was central to Korean society, and by this logic, the maintenance of health was one of the most highly valued responsibilities. Rather than retroactively treating illness after the body has devolved, Confucian values called for a proactive maintenance of health.

Yaksikdongwon Ideology

Food and diet were considered more important than medicine, if not actually the medicine itself. This is epitomized in the ideology of yaksikdongwon. This philosophy states that “medicine and food are fundamentally the same” and it took precedence in Joseon’s royal kitchens (8). It is no surprise that Lady Yi likewise valued food as medicine and prescribed to this yaksikdongwon ideology.

Lady Yi’s value of yaksikdongwon supports Ro Sang-ho’s claim in “Cookbooks and Female Writers in Late Joseon Korea” that Lady Yi was not a revolutionary in writing her encyclopedia, but rather a renovator. Prior culinary books written by men “were interested in the health and medicinal benefits of particular foods” (9). Lady Yi maintains this motivation in her work. While she deviates by describing how to make foods and writing specifically for a female audience, the recipes she chose reveal what she deems valuable knowledge. Lady Yi’s yakgwa recipe not only demonstrates Lady Yi’s own adherence to yaksikdongwon, but also the cultural significance of understanding foods, like yakgwa, as medicine.

Works Cited

(1) Noh, Leann. “Art and History of 'Hangwa'.” The Korea Times, 19 Jan. 2012, http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/art/2012/01/135_103227.html.

(2) Yoon, Seo-seok, et al. Festive Occasions: The Customs in Korea. Ewha Womans University Press, 2008.

(3) Yeon, Dana. “Traditional Korean Cookie Delights.” The Chosun Ilbo (English Edition): Daily News from Korea - Inside Korea > Food, 3 Feb. 2011, https://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2011/02/03/2011020300107.html.

(4) BonBon 봉봉 . “Dessert of the Rich and Noble: Yakgwa 약과.” Sesame Sprinkles, 20 Aug. 2021, https://sesamesprinkles.home.blog/2019/05/02/yakgwa/.

(5) Chang Ssi, Andong, et al. Ŭmsik Timibang: Kyugon Siŭibang 음식 디미방. Kungjung Ŭmsik Yŏn'guwŏn, 2000.

(6) Pettid, Michael J., and Kil Cha. The Encyclopedia of Daily Life: A Woman’s Guide to Living in Late-Chosŏn Korea. University of Hawai’i Press, 2021, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1bn9jks.

(7) Pettid, Michael J. "Science, food and health in Chosoˇn Korea." The Routledge History of Food. Routledge, 2014. 93-110.

(8) Chung, Hae-Kyung, et al. "Recovering the royal cuisine in Chosun Dynasty and its esthetics." Journal of Ethnic Foods4.4 (2017): 242-253.

(9) Ro, Sang-Ho. "Cookbooks and Female Writers in Late Chosŏn Korea." Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 29.1 (2016): 133-157.