Drawn to Build: Reconstructing the Yotsume-gaki

Introduction

“Yotsume-gaki”

Whether on the walk to work down a residential street in Tokyo or on a leisurely stroll through a traditional Japanese tea garden, spans of modest bamboo fencing remain an inconspicuous sight in many of Japan’s built environments.

Fig. 1 (Left): A bamboo fence along a residential street in Tokyo, Japan. Fig. 2 (Right): A bamboo fence and gate in the Ozawa Residence, Sendai, Japan.

The specific type of fence featured in the 19th-century Zen garden and on the 21st-century city street is called the yotsume-gaki, literally meaning “four-eyed fence” likely in reference to the four spaces formed in each vertical row by the crossing bamboo canes (although variations of the yotsume-gaki exist in which there are fewer “eyes” in each vertical row). Compared to other kinds of bamboo fences, the yotsume-gaki is a relatively simple construction; the fence type is coded as a composition of two primary components, the vertical posts (tateko) and horizontal beams (dôbuchi), slung to one another at the crosses with twine. Thicker timber posts (oyabashira) terminate the fence at its ends, while intermediate timber posts (mabashira) are used to attach spans of dôbuchi together to extend the length of the fence as needed [1].

Fig. 3: A schematic drawing of yotsume-gaki fencing.

While there are no extant bamboo fences, bamboo fence construction near certainly traces back to ancient times by virtue of the material’s qualities - its rapid growth, natural sturdiness, wide geographical range, abundance, and ease of manipulation. The earliest pictorial depictions of the yotsume-gaki date back to the Heian period (794 – 1185) picture scrolls (emakimono), but it was not until the start of the Momoyama period (1573 – 1615) and onwards that bamboo fence typologies saw profound development in parallel with the development of chanoyu (the Japanese ceremonial culture centered on tea) as a social, countercultural movement emphasizing modesty amidst rapid economic expansion and a growing luxury commodity culture [2]. In chanoyu’s aesthetic of austerity and natural elegance did the simple yotsume-gaki find its position as the most popular fencing of choice in Japanese tea garden design, and it remains as “probably the most widely constructed bamboo fence in Japan” to this day [1].

Experiment: Reconstruction from Illustration

Whether in 13th-century narrative handscrolls or 18th-century pictorial travel guides, there is no surprise that historical illustrations consistently depict the inconspicuous yotsume-gaki through simple, economical linework, as can be seen below:

Fig. 4 (Left): Selection from a 13th-century handscroll, Ippen Shōnin Eden. Fig 5. (Right): Selection from a 18th-century travel guide, Miyako rinsen meishō zue.

I aimed to interrogate the yotsume-gaki’s reputation as the “simplest” form of bamboo fence construction as well as the extent to which non-instructional, illustrative depictions of the yotsume-gaki could be used as a design template for real construction by building the yotsume-gaki myself threefold. In the first iteration, I analyzed two forms of illustrated historical documentation that included images of the yotsume-gaki - 13th-century emakimono and 18th-century zue publications - and used solely the drawn depictions from these primary sources as the reference for the design and construction of the fence. In the second iteration, I referred to a contemporary Japanese bamboo fence construction manual that provided explicitly instructional guidelines and illustrations for the traditional method of hand-constructing yotsume-gaki fences and built a span of fencing as close to the instructions provided as possible. In the third and final iterations, I reconstructed the first fence while incorporating building techniques learned from the contemporary instructional manual in an ultimate attempt to achieve more closely an accurate reconstruction of what a span of yotsume-gaki might have looked and functioned like in historical built contexts.

Through these iterative experiments in hand-constructing spans of yotsume-gaki, I sought not only to investigate how reading historical Japanese style line-illustrations can inform design in the translation from drawing to construction, but to explore how reconstruction from such informally architectural drawings may teach us about the programmatic and functional purposes of the yotsume-gaki, and other fencing types, in their built environments.

Iteration 1

Primary Sources - Consulting the Emakimono and Zue

As briefly mentioned, the two types of primary documentation I referred to were the 13th-century Heian period emakimono and the 18th century Edo period zue publications.

The term emakimono translates to “picture scroll” and refers to a traditional form of painted handscroll in which an illustrated and written narrative would unfurl as the reader unwound the scroll. In these such scrolls were the yotsume-gaki-type fence first recorded. One example is an emakimono titled “Ippen Shōnin Eden” ("Illustrated Biography of the Itinerant Monk Ippen") from 1299 that features images of fencing throughout the continuous landscape. While the yotsume-gaki are not particularly prominent nor typological (the fences are shown assembled in a similar, see-through manner but without the emblematic order of four dôbuchi) in the overall composition, the painting does offer insight into the contexts of use; we can see the fencing used to mark plots of farmland, demarcate property lots, and line along pathways.

Fig. 6: Selection from Ippen Shōnin Eden showing example representations of yotsume-gaki-type fences.

Zue (meaning “illustrated” or “pictorial”) publications were first widely circulated in the mid-18th century amidst an economical shift of production away from urban centers to rural regions that led to the proliferation and popularization of distinctive regional products, necessitating the new genre of travel guide publication to inform readers of famous crafts, foods, and locations across Japan [3]. The abundant illustrations in zue books were subtly embellished depictions of life and production in the locale but also maintained an important degree of informational accuracy in describing what these famous places were like, such that the zue could serve as both visual entertainment and as a functionally informative travel guide [4].

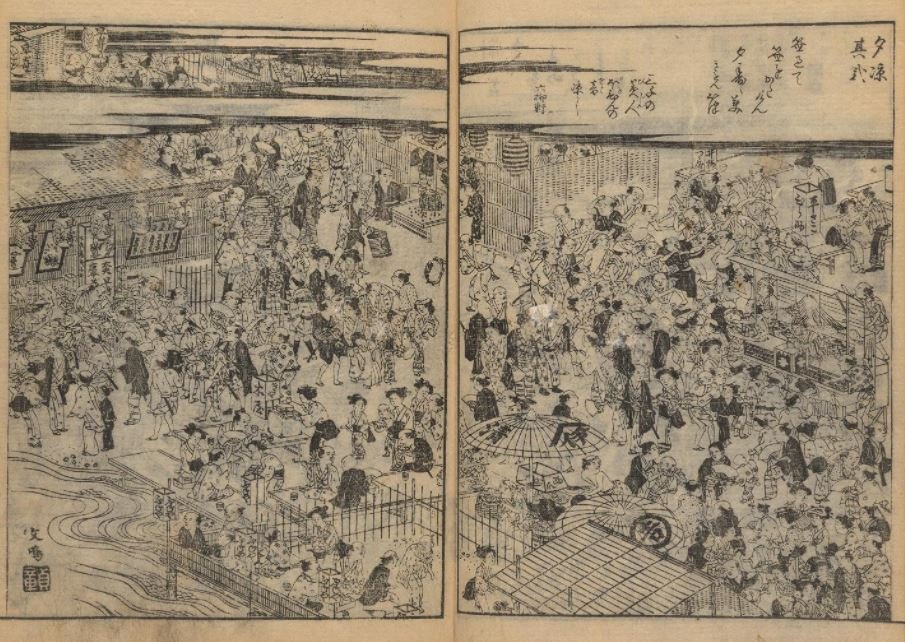

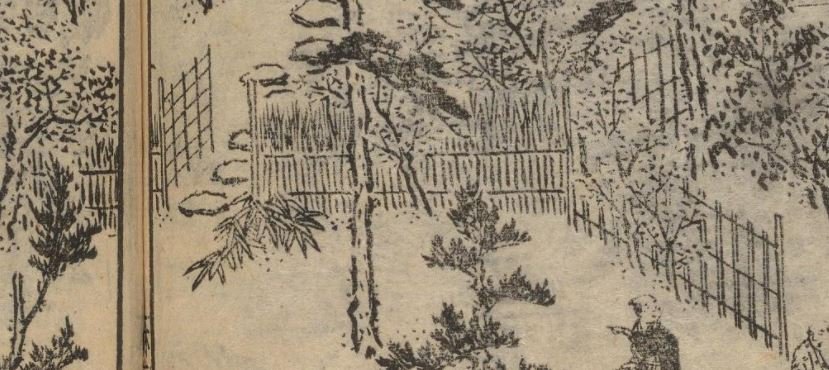

The two zue publications I analyzed were Miyako Rinsen Meishō Zue (“Famous Gardens in Kyoto”, six volumes, 1799), a guide to notable gardens, temples, and public spaces in Kyoto illustrated by artists Sakuma Sōen, Nishimura Chūwa, and Oku Bunmei, as well as Nihon Sankai Meisan Zue (“Famous Local Products in Japan”, five volumes, 1799), a guide to regional crafts, foods, and natural resources from various locales throughout the country [4]. The zues place the yotsume-gaki in a wide variety of built contexts - such as for screening in tea gardens, lot markers in plazas and marketplaces, fencing around greenery, and barriers on beaches.

Fig. 7 (Top left): Selection from Miyako Rinsen Meishō Zue featuring yotsume-gaki in a garden. Fig. 8 (Top right): Selection from Miyako Rinsen Meishō Zue featuring yotsume-gaki in a public plaza. Fig. 9 (Bottom left): Selection from Nihon Sankai Meisan Zue showing yotsume-gaki on a beach. Fig 10 (Bottom right): Selection from Nihon Sankai Meisan Zue showing yotsume-gaki in a courtyard.

From observing the drawings across the emakimono and the zues, we can identify some common drawing conventions for representing the yotsume-gaki. Nearly in all cases, the fence members are drawn with single-width brushstrokes, double lines only being used to perhaps suggest thickness in the bamboo or timber used for end posts. In some examples, especially in the more rural scenes in the emakimono and the Nihon Sankai Meisan Zue, the fencing is drawn in a very casual, irregular manner, as opposed to other examples of yotsume-gaki in public, urban, or sophisticated contexts in which the linework for the fencing is much more rigid with regular spacing and consistent lineweights. Does the quality of illustration speak to the quality of the material and construction? Or rather, are the variations in depictions merely a feature of style from the individual artists?

From what can be extrapolated, we can see that the illustrated yotsume-gaki serve as transparent visual screening, are head-level height at their tallest, come in a wide variety of designs (while staying within the general code of assembly), and are placed not in contexts of physical security, but moreso as visual demarcations of space and purpose of space.

Designing Fence Iteration 1

In essence, yotsume-gaki construction poses two elements of design: quality of the bamboo material and proportion of member spacing. With the material being a given, as I could only acquire bamboo poles 6’ in length and ⅜” to ¾” in width, I turned to an analysis of the member proportions represented in the primary sources to determine a design for the first fence that would be representational of a historical model.

I scanned through Ippen Shōnin Eden and pored through all of the volumes of Miyako Rinsen Meishō Zue and Nihon Sankai Meisan Zue to document every instance of yotsume-gaki representation I could identify:

While exact horizontal proportions were difficult to identify, the most common pattern of spacing between tateko puts them relatively closer together than farther apart. In terms of the vertical spacing of the dôbuchi, the most common assembly (14 of the 52 instances analyzed) only featured two horizontal members with an “A-B-A” pattern in which the “A” vertical spacing was shorter than the central “B” spacing. Most of the fencing depicted across the three sources also place the top of the fence at roughly head height, between five to six feet tall at my best guess. As mentioned, it was unclear from the illustrations exactly how the horizontal and vertical members were joined together, but with the only clue being a few drawings showing the horizontal spans crossing in front of all of the vertical spans, I opted for that type of assembly in my first construction.

Fig. 11: Selection of a detail from Miyako Rinsen Meishō Zue showing yotsume-gaki construction with horizontal beams assembled in front of a linear row of vertical posts.

The design principles I gathered from the primary sources for the first yotsume-gaki build were as follows:

Consistency in bamboo thickness between all members.

Close spacing between vertical members.

“A-B-A” spacing between horizontal members, with length “A” being shorter than length “B”.

Fence height at head level.

Horizontal members slung in front of a linear row of vertical members.

Building Fence Iteration 1

In the spirit of historical reconstruction, I opted to use hand tools for the first iteration of yotsume-gaki construction. An architecture professor well versed in bamboo construction helpfully lent me a set of tools including a bamboo saw, bamboo splitter, and bamboo machete, and I procured my own garden twine for slinging members together. I picked 6 similarly thick pieces of bamboo from my stock for the vertical members and determined the positions and proportions for the fence on the spot, as I’d imagine much of bamboo fence construction in the built contexts discussed above would have been in situ. I separated the vertical posts by 3 inches each and placed the two horizontal members, picked for their consistent thickness, such that the “A” spacing would be 18 inches and the “B” spacing would be 36 inches.

I then hand-sawed the horizontal members to length at 24 inches, which proved to be much more difficult than initially anticipated - the sawteeth would catch between the bamboo culm walls once sawn through to the hollow center of the pole, and the bamboo itself is sturdy and quite resistant to quick sawing. As evidenced by the historical documents, the fences would normally be posted into the ground, but because I did not have access to any land to build directly into, I had to compromise and post the vertical members into a wooden board.

There were some initial difficulties in keeping the bamboo secured in place while lashing the members together, which I did in a simple crossing pattern tied with a knot with a long piece of twine. I simply posted the rest of the vertical members in the board, repeated the knotted lashing between members, and completed crafting the first iteration of the yotsume-gaki.

Iteration 2

Secondary Source - Consulting Yoshikawa

Isao Yoshikawa, graduate from the Architecture Department of Shibaura Technical University and establisher of the Japan Garden Research Association in 1963 [1], provides an instructional set of illustrations and guidelines for the construction of yotsume-gaki fencing using traditional building methods in his book Building Bamboo Fences:

Fig. 12: Instructions from Yoshikawa’s Building Bamboo Fences on how to build yotsume-gaki.

Yoshikawa’s manual clearly provides more clarity than the emakimono and zue publications analyzed earlier in how the fencing is meant to be assembled from a constructional standpoint - the most significant differences between the design provided by Yoshikawa and the historical documents being the explicit expression of thicker timber end posts, whereas in the primary sources there were only nondescript suggestions of such an element, and the instruction to post the vertical tateko in an alternating pattern around the horizontal dôbuchi, as opposed to the suggestion in the primary sources to lash the beam on one side of the linear row of posts.

Designing Fence 2

Yoshikawa offers some design principles in yotsume-gaki construction as follows:

“...the traditional yotsume-gaki is with four levels..”

“...arranging the second and third dôbuchi from the top a little closer and making a square space with tateko gives good balance.”

“Making the length of tateko above the first dôbuchi from the top longer than the others below will give a well-balanced appearance…”

The tateko are posted in an alternating pattern along the length of the dôbuchi.

Following the above principles [1], I designed a span of yotsume-gaki by translating the proportions given by Yoshikawa’s drawing to the dimensions of the bamboo I had available (the operative dimension being the maximum 6’ length of the horizontal spans), resulting in a fence design shorter in height than what Yoshikawa describes in his example but proportionally similar regardless.

Building Fence Iteration 2

I separated the bamboo poles for the dôbuchi and tateko according to consistency in thickness before cutting them down to size using a miter saw. After sawing the cedar posts, I had to screw them into the baseboard to again simulate the sturdiness of a post that should otherwise be embedded into the ground.

I inserted the horizontal beams into the end posts, needing to stress and bend the bamboo poles into place so that they would fit in the slots between the rigid spacing between the cedar posts. The vertical posts then went into the base in an alternating fashion and were tied to the fixed horizontal members using the ibo-musubi method. This lashing technique proved to be much more economical, requiring short lengths of twine, and practical as it kept the members more tightly in place than the improvised cross-and-knot technique I employed in the first iteration.

Iteration 3

Adjustments to Design

The third and final leg of the yotsume-gaki construction experiment involves taking what has been learned about fence building techniques from an explicitly instructional guide in the second iteration and applying those techniques and accrued tacit knowledge in adjusting the first, more historically-backed iteration in an attempt to achieve a more historically accurate reconstruction of the yotsume-gaki.

As the visual design for the first iteration was solidly supported by the illustrated material present in the emakimono and the zue publications, the primary adjustments to the first iteration lie in the assembly of the fence, that is, in changing the organization of the vertical tateko from a linear row to an alternating pattern and in changing the lashing method from the improvisational cross-and-knot tie to the ibo musubi method.

Building Fence Iteration 3

I disassembled the first fence iteration to use the same bamboo poles in the reassembly and maintain the original dimensions and design. Using the original baseboard, I prepared a new base with slots bored at the same intervals, but now alternating across the centerline where the horizontal dôbuchi would be lashed to the tatekos.

The rest of the construction followed similarly as in the first iteration, but there was a notable moment of easier construction as compared to the first attempt in which the alternating posts kept the horizontal members in place during the first few lashes, whereas in the first iteration I needed to lash the first pair of vertical and horizontal members together before posting the fence into the base so that the members would stay connected.

The resulting final fence build was much more sturdy and balanced compared to the initial trial. The first fence was back-heavy due to the how the dôbuchi were lashed to the tateko on one side while the latest trial remained centered as the weight of the dôbuchi was held in the middle by the alternating tateko. The ibo-musubi lashings were also easier to tie securely and held the members in place more tightly, and were less prone to loosening.

Final Images

Conclusion

Results

In terms of the goal to build functional spans of yotsume-gaki based on historical illustrations, the experiment showed to be successful. Clearly, there were gaps in knowledge when translating the original emakimono and zue drawings into physically built practice, specifically in the order of assembly and constructional connections between members, but the illustrations provided a strong visual template against which my recreation convincingly resembles. Because the yotsume-gaki is traditionally considered a feature of design rather than structure, perhaps the details of assembly recede to the background in terms of importance. The attention to design over assembly reflected in the historical drawings, which accurately capture spacing proportions but only vaguely suggest structural connections between members, if at all, could point to the notion that the actual assembly of the fencing is of little concern as long as the yotsume-gaki achieves its intended visual and spatial purpose in its context of use. Thus, the non-instructional drawings from the emakimono and zues examined could actually serve as an instructional set of templates for yotsume-gaki design if spacing proportion design is the dominant priority. As Yoshikawa remarks, “it is unexpectedly difficult to make an attractive fence”, so an illustrated guide full of famous examples could prove to be a powerful manual itself for yotsume-gaki construction [1].

At the same time, the technique of assembly indeed makes a significant difference in the function of the yotsume-gaki, even under the assumption that they were used as predominantly visual screens as opposed to physically protective barriers. The first iteration with linear tateko was much more unbalanced than the third iteration with alternating tateko, and the method of ibo-musubi lashing was much more economical in resource usage and provided for much sturdier connections between members as compared to the improvised cross-and-knot tying. As far as imagining my fence experiments existing in the contexts of use illustrated in the historical documents, my constructions support the notion that yotsume-gaki were not used for physically protective purposes (it would not be incredibly difficult to force oneself past such a construction), but the third iteration, being considerably sturdier than the first, could feasibly be used reliably as a garden screen, path lining, or farmland fencing. The point being, the construction experiment does reinforce the historical continuity of a fence design that, in its simplicity, economy, and robust quality of material, suffices in its purpose as a dependable visual demarcator of space.

Reflection on Experiment

I can strongly argue that my third iteration of the yotsume-gaki build is convincingly historically grounded because, simply enough, the final result closely resembles the fencing present in the emakimono and zue illustrations. As far as visuals go, my final iteration is an accurate replica of fencing from 18th-century Japan because I used the historical drawings as a direct design template, and while the exact techniques of assembly may not be completely accurate, the third iteration’s apparent sturdiness does make the reconstruction a functionally accurate model as well. While there is no way to know exactly how the historical fencing was assembled as the subjects of the illustrations are not standing to this day, Yoshikawa claims that the methods he described (and I employed) are a traditional way to craft the yotsume-gaki, and given the wide variety of different yotsume-gaki constructions (and assumedly, different construction methods) found in the drawings, my method of fence building in the third iteration could very well be one historically accurate form. At the very least, since Yoshikawa’s construction model is contemporary and based on existing traditional examples and the continuity of the craft, the third iteration does indeed serve as an accurately traditional model, even if not an accurate replica of the fencing depicted from 18th-century Japan.

There are two primary areas of improvement for the experiment I posed. Firstly, it is impossible to truly simulate the sturdiness of the yotsume-gaki design without actually posting the fence into the earth or building longer spans of fencing. If possible, building the yotsume-gaki into the ground and building it longer as it would actually be built would better model the function of the fencing shown in the primary sources, and thus better simulate its function in context. Secondly, my reference material was limited to three sources, with most of my design template being from a pictorial guide to 18th-century gardens in Kyoto, limiting my scope in region, location, and type of drawing. It would be more appropriate, if possible, to search for more examples of such illustrations across more time periods to gather a more comprehensive survey of how bamboo fencing has been represented throughout time and space to ultimately offer more area for experimentation in reading such drawings to translate from illustration to construction.

Works Cited

[1] Yoshikawa, I., 2010. Building Bamboo Fences. Tokyo: Graphic-sha Pub. Co.

[2] Keane, M., 1996. Japanese Garden Design. North Clarendon: Charles E. Tuttle Company.

[3] Guth, C., 2021. Craft Culture in Early Modern Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

[4] Yoshimura, R., 2020. LONELY PLANET in Edo-period Japan: Meisho Zue. [online] Freer Gallery of Art & Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. Available at: <https://asia.si.edu/lonely-planet-in-edo-period-japan-meisho-zue/> [Accessed 5 December 2021].

Images Cited

Fig. 1: Yoshikawa, I., 2010. Building Bamboo Fences. Tokyo: Graphic-sha Pub. Co.

Fig 2: Keane, M., 1996. Japanese Garden Design. North Clarendon: Charles E. Tuttle Company.

Fig 3: Yoshikawa, I., 2010. Building Bamboo Fences. Tokyo: Graphic-sha Pub. Co.

Fig 4: En'i (円伊). 1299. Ippen Shōnin Eden (一遍 上人 絵 伝, "Illustrated Biography of the itinerant monk Ippen"). [Paint and ink on silk handscroll].

Fig 5: Akisato, Ritō. Miyako rinsen meishō zue v. 1, pt. 2. Naniwa: Kawachiya Tasuke, doi: https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.893153.39088019040633

Fig. 6: En'i (円伊). 1299. Ippen Shōnin Eden (一遍 上人 絵 伝, "Illustrated Biography of the itinerant monk Ippen"). [Paint and ink on silk handscroll].

Fig. 7: Akisato, Ritō. Miyako rinsen meishō zue v. 1, pt. 2. Naniwa: Kawachiya Tasuke, doi: https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.893153.39088019040633

Fig. 8: Akisato, Ritō. Miyako rinsen meishō zue v. 1, pt. 2. Naniwa: Kawachiya Tasuke, doi: https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.893153.39088019040633

Fig. 9: Shitomi, Kangetsu. Nihon sankai meisan zue, v.3, doi: https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.892779.39088019036359

Fig. 10: Shitomi, Kangetsu. Nihon sankai meisan zue, v.5, doi: https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.892779.39088019036359

Fig. 11: Akisato, Ritō. Miyako rinsen meishō zue, v. 1, pt. 2, Naniwa: Kawachiya Tasuke, doi: https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.893153.39088019040633

Fig. 12: Yoshikawa, I., 2010. Building Bamboo Fences. Tokyo: Graphic-sha Pub. Co.