The Craft of Urushi (Japanese Lacquerware)

Images source: The MET

Commonly referred to as china across the world, we have come to familiarize ourselves with the distinguishable “Blue and White” Chinese porcelain wares and acknowledge the country’s exquisite craftsmanship. The term “china” resulted from the strong association between the highly valued commodity with its origin of imports. As the porcelain began to arrive in high volume and eagerly acquired by Westerners, the term became synonymous with the object itself.

Have you ever wondered if such labeling of a craft and material object, specifically attaching it to its origin, is a unique phenomenon?

In fact, this was not a single occurrence. As its popularity grew rapidly in Europe, the Japanese lacquerware, specifically its distinguishable maki-e lacquered objects with intricately decorated gold and silver, became referred to as “japan” in the 18th and 19th centuries, since the best urushi ware was identified as coming from Japan. (Gonroku pg7)

Japanese lacquerware is a historically long recorded and significant craft culture that is deeply connected to the culture and lives of Japanese people. While the craft was prominent in other Asian countries as well, Japanese urushi ware stands out uniquely, showcasing its charm through a rich variety of styles, sophisticated techniques and diverse products (The Japan Kōgei Association).

History of Japanese Urushi Ware

Unearthed from archaeological sites from the early Jomon period, about 7000 years to 5,500 years ago, the many examples of earthenware, wooden containers, combs and worn ornaments that used lacquer tree sap confirmed that lacquer was first used in Japan around then, if not sooner (Hidaka).

Since the Heian period (8th - 12th century), a time when court culture flourished in Japan, the craft have been refined and developed. However, it was not until around the 11th century that lacquerware became accessible and spreaded to the general public in Japan, among the Samurai, Buddhist monks, priests, and urban merchants. (Hidaka) In truth, lacquerware remained a luxurious commodity at that time, yet they can now be mass produced for cheaper cost given a new method that tops the initial rough coating with one or two coats of lacquer, instead of traditionally having numerous layers. By the 16th century, the wares were used among farmers as well.

Under the Edo period from the start of the 17th century, lacquerware varied in styles and products as the craft techniques developed. Moreover, extending beyond just a craft culture, the material object cultivates certain social behaviors and dynamics at the local community level. For instance, major ceremonies such as weddings and funerals would require many pieces of lacquered tableware, so “it was common to borrow the tableware from other families or share them as a community,” (Hidaka) This portrays the extensive spread of lacquerware as a production practice as well as a material culture.

Trade and the Circulation of Lacquerware

Japanese urushi ware first became known in Europe when Portuguese and Spanish Jesuit missionaries and traders came to Japan and brought back a large quantity of lacquered objects in the mid 16th century. The commodity was exported “mainly to Portugal and Spain then England, the Netherlands, and other countries.”(Hidaka) From the 17th century onward, the Netherlands became the sole exporter of Japanese-made lacquerware after the Tokugawa shogunate granted permission to trade with Japan only to the Netherlands.

A raden and maki-e decorative coffer for export (16th to 17th century) (Collection of National Museum of Japanese History) (12.7 cm x 23 cm x 15.5 cm)

The export happened through the Dutch settlement and trade hub in Nagasaki with a practice that is worthy of interest. In recognition of the different lifestyles between Japan and those of European countries, most of the lacquerware to be exported were specially created on an order-by-order basis from Dutch merchants in Kyoto, the main centre for manufacture for mainly maki-e wares. Thus, this exchange explains the presence of Japanese-made lacquerware in old European castles and museums, ranging from chests with many drawers, large coffers to tablewares. While lacquerware was also imported from other Asian countries, “japan” was particularly admired and made its way onto “lists of assets of the 17th century European aristocracy,” revealing the high-value of the commodity.

The Japanese lacquerware also gained popularity in other Asian countries, including that of those in East Asia and Southeast Asia, since the 10th century for its traditional maki-e technique that was not used elsewhere.

The Craft and Its Production Process

The making of lacquerware is a meticulously detailed and time-consuming process that involves many steps, specialized tools and highly skilled artisans. Essentially, the production process operates on a system of division of labor where one or more artisans may be tasked to work a particular stage from the fabrication of the substrate, preparation of the ground coating layers to final decoration (Laurin)

The Urushi Tree and Its Cultivation

Often translated to “lacquer” in English and used rather interchangeably, yet urushi and lacquer are in fact very different from one another. Urushi refers to the natural, milky tree sap of the urushi tree that originally grows exclusively in the monsoon region from East Asia to Southeast Asia. Often seen in the countryside and the mountains, the urushi trees require specific conditions for growth: humid climate, direct sunlight, rich soil, and exposure to wind. At the beginning almost all urushi trees grew in the wild, but as the demand for sap increased, human cultivation began on a large scale with the groves located at an accessible distance for effective sap collection. This process is evident to have started as far back as the Nara period (710-794), where the sap was collected as a form of land taxes, if not earlier. During the feudal periods such as the Edo period (1615-1868) where local lords encouraged the cultivation of urushi trees (Gonroku 68). Although Kyoto was the manufacturing center, the different clan domains in such as Edo and Kaga enacted policies that encouraged the development of local industry that gave rise to the variety of urushi unique to each region. For instance, Wakasa-nuri, Tsugaru-nuri and Shunkei-nuri are typical examples of regional urushi types (The Japan Kōgei Association).

Image source: Japan National Tourism Organization

Granted differences in regional climate and habitat, the urushi trees found in other Asian countries differ from the Japanese trees from their trunks, flowers to the sap. Specifically zooming into the East Asia region, the Chinese trees and its sap resemble the Japanese, while the Korean sap is similar to the Chinese sap as a result of the similarities in climate and natural conditions between the growing habitats among these three countries (Gonkoru 71).

When it comes to harvesting the sap, time and skill are at the forefront. The best time to harvest is when the trees are about twelve years old and during a time span around June into November. Whereas, the procedure of incising and gathering requires structure and precision as a particular harvest time and incision yields a different type of sap suitable for specific functions. (Gonroku 71)

There are many uses to urushi, but surprisingly are little known: it can act as a herbal cure for hyperacidity, its buds and fruits are edible, and it can be used as thread for weaving textiles or adorn silver or gold foil (Gonkoru 90-92). Bringing the focus back to the craft practice in discussion and specifically within the geographical context of East Asia, urushi is used exclusively as a coating and adhesive.

Processing of the Sap to the Coating Layer

The natural sap (arami), usually brown or amber color, gathered from the trees cannot be used for coating as it is, but is required to undergo an extended process, which begins with the process of filtering out impurities to yield ki-urushi, or raw urushi, that is an oily, milky-colored substance. Next, the substance undergoes kurome, a heating process either under the heat of the sun or charcoal fire to remove moisture and makes the urushi semitransparent, while the solution is being slowly mixed (nayashi). This refining process produces a transparent product called suki-urushi (Gonroku 77).

The processed urushi can either be used in its transparent state or mixed with pigments to make colors, such as iron filling, shiō (a yellow pigment imported from China), or natural cinnabar (Gonkoru 78-80). Aside from black and red, urushi typically came in seven colors at most in the past with the rest being yellow, green, flesh color (mix of yellow and vermillion), and neutral color (combination of green and red), and indigo (Gonkoru 80). Particularly, the color white cannot be produced. Upon this stage, the urushi coating is ready to be applied to the object.

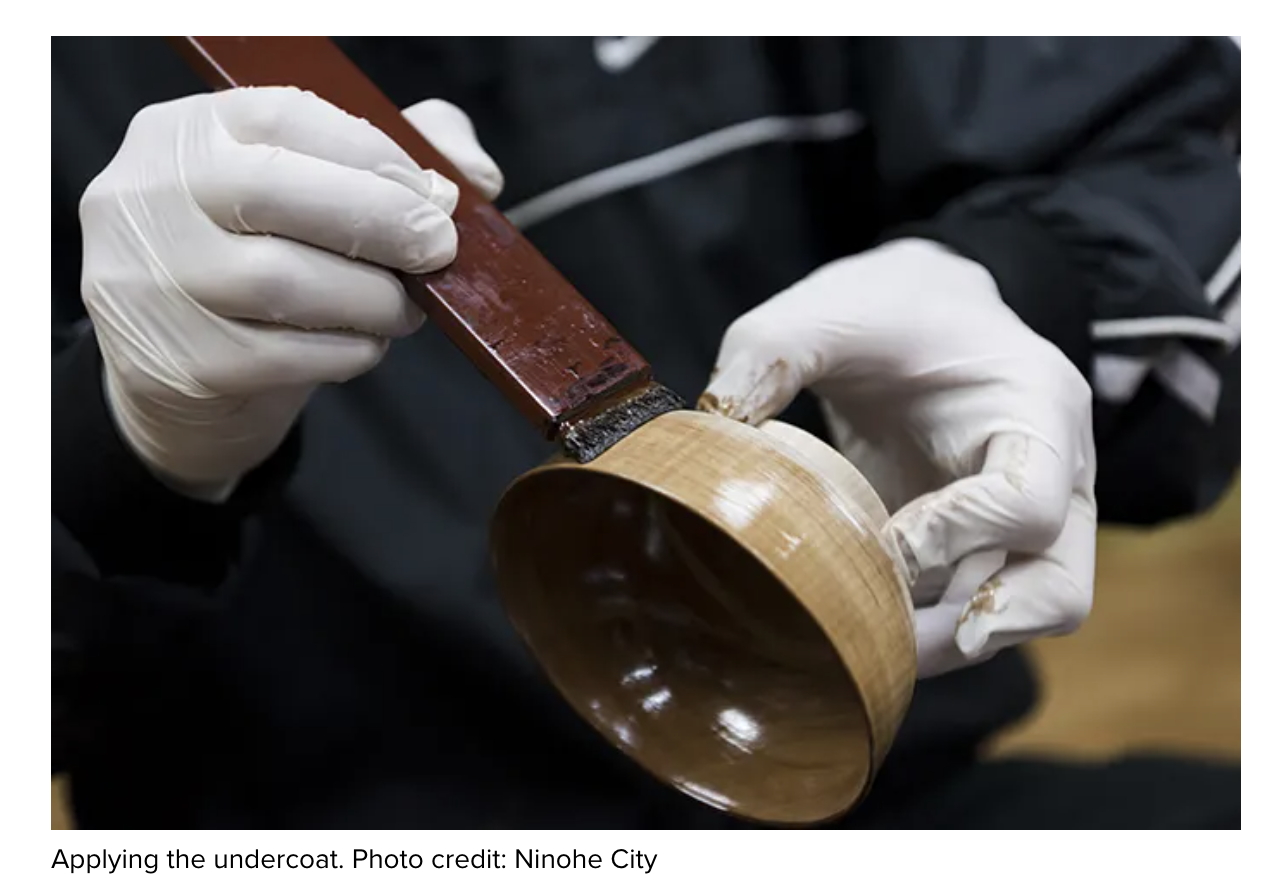

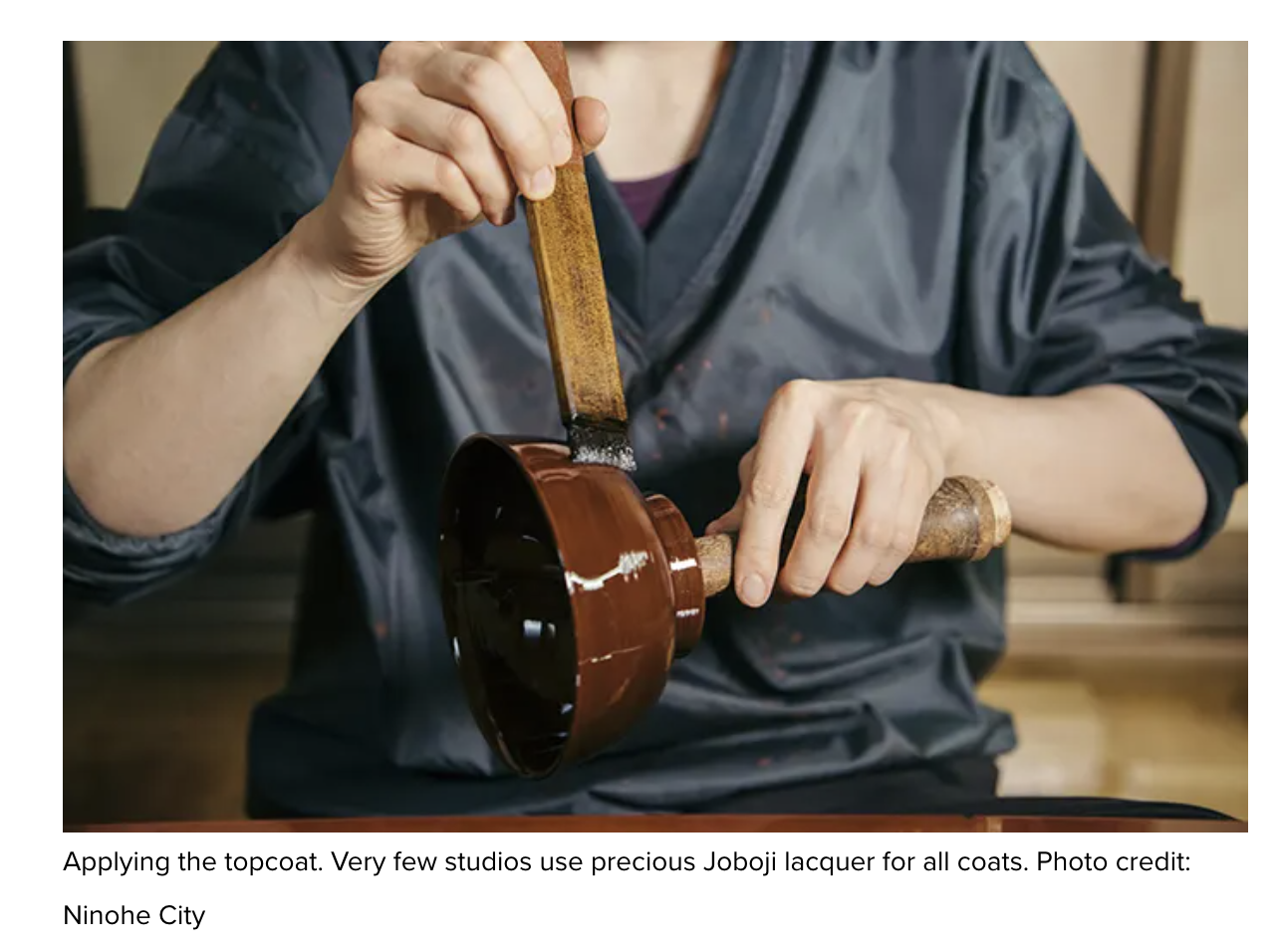

Coating Urushi Ware

The art of urushi ware is multimedia craft in practice. As Gonroku Matsuda, a Maki-e master, described in his publication work on urushi, “in essence, urushi is a type of coating; it has no form in and of itself. It is only in its relationship to the substrate, the body of the object, that it takes on useful meaning,” (93) highlighting the interconnectedness between the art form and material objects in relation to physical properties and functions. The oldest type and most widely used substrate is wood, largely attributed to the finish objects being light, easy to handle and used in large structures. Other types of substrate include metal, paper, cloth, bamboo, pottery and leather.

Depending on the types of substrate and how well urushi sticks to the surface of that substrate, the coating process takes on a different method and order, such as adding undercoating or base coating. Moreover, the types and number of layers of coating also vary between substrates and the desired looks of the finished object determined by the artists’ personal discernment and insight, which was “an important distinction in the art of urushi ware and one that required the utmost care” (Gonroku 96).

There are three main types of base coating: honkatagi, honji, and makiji, of which only the honkataji is still in practice today (Gonroku 96). Next comes the lower, middle and upper layers of urushi. In between these coating layers, the ware needs to sit out so that moisture can be removed. How long depends case by case, but it can range up to several years between layers. Lastly, the substrate will be polished and ready for decorations.

Images source: Japan National Tourism Organization

Decorating Urushi Ware

In the past, most utilitarian urushi ware were monochromatic black and red. As decorative techniques developed and adopted, the wares became adorned with variations of designs.

The most famous Japanese traditional technique is Maki-e, which literally translates to “sprinkled picture decoration” and characterized by the featuring of pictorial elements and patterns as well as the sprinkling of fine gold or silver powder over a black background surface (The Japan Kōgei Association). Although there is a theory relating the origin of this technique to China, the text argued that “at present there is no evidence that the makkinru technique – that is, maki-e – existed in China, we must conclude that maki-e originated and developed in Japan” (Gonkoru 102). This technique saw great development during the Heian period and became the primary method of decorating urushi ware. The main types of maki-e are togidashi maki-e, hiramaki-e, takamaki-e, and shishiai maki-e which each takes many forms and technical diversity (Gonroku 103).

While maki-e is used often as the sole means of decoration, it is also common to see combinations with other decorative techniques, such as raden (mother-of-pearl inlay), heidatsu and hyōmon (thin gold or silver inlay technique dated to the Warring States period in China), chōshitshu (carved lacquer) to kinma (incised design technique originated in Thailand) and many more.

A Comparative Lens on Regional Characteristics of Lacquerwares in East Asia

As previously mentioned, lacquerware remains a regional trademark of East Asian and Southeast Asian, with notable similarities and variations arising from differences in natural environments for plant cultivation, cultural preferences, and material needs. Whereas Japan is known for maki-e wares in East Asia, its neighbor Korea developed its unique mother-of-pearl inlay (using tortoiseshell and metal wire) as the dominant decorative technique (The MET), and China known for its carving designs on thick-layered coats (Park).

Image source: The MET

Thus, not only does the urushi ware and its rich history demonstrate the supreme achievements of Japanese decorative arts, but the craft also highlights the mutual exchange and mobility of knowledge in craftsmanship.

Cited Sources

[1] The MET. “Lacquerware of East Asia.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Department of Asian Art, www.metmuseum.org/essays/lacquerware-of-east-asia. Accessed 21 Mar. 2025.

[2] Gonroku, Matsuda. The Book of Urushi: Japanese Lacquerware from a Master. Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, 2019.

[3] Hidaka, Kaori. “The History and Culture of Lacquer in Japan.” Public Relations Office of the Government of Japan, 2022. https://www.gov-online.go.jp/eng/publicity/book/hlj/html/202205/202205_01_en.html

[4] Laurin, Gina. “The Craft and Care of East Asian Lacquer.” Denver Art Museum, 2013. https://www.denverartmuseum.org/en/blog/craft-and-care-east-asian-lacquer#:~:text=To%20avoid%20light%20damage%2C%20lacquer,to%20collect%20the%20raw%20sap.

[5] Park, Ji-won. “National museum exhibition compares Asian lacquerware techniques and cultures” The Korea Times, 2021. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/art/2025/02/398_320900.html

[6] The Japan Kōgei Association. “Urushi Work.” Nihon Dentō Kōgei Kanshō no Tebiki (Handbook for the Appreciation of Japan Traditional Art Crafts, 2003. https://www.nihonkogeikai.or.jp/en/urushiwork