Folding Fans of East Asia

Development of the Folding Fan

Handheld fans were commonly used before the invention of air conditioning and electric fans. They are still often seen in cosplays or traditional dances. The type of fan used for these purposes is the folding fan and its origins lie in East Asia. As with many East Asian crafts and concepts, the idea of who “first” came up with the idea of the folding fan is contested between scholars who advocate that it was first invented in China during the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420-589 AD) and others who believe the folding fan was invented in Japan around 670 AD and later introduced to China during the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127 AD) [1][2]. Instead of looking for who the “original” is and who the “copies” are, the interactions between the countries and the developments from these interactions are more interesting to look at.

Focusing on the interactions in East Asia, round, non-folding fans were first developed in China. These were then transported to Japan where the design of the folding fan or “sensu” was created and the fans were sent back to China as court gifts [3]. The first introduction of the folding fan to China from Japan was actually through Korea. In the 7th year of Xi Ning in the Northern Song Dynasty (1074), a North Korean envoy brought “a folding fan made of crow blue paper with figures, animals and flowers and birds” to China on his visit [4].

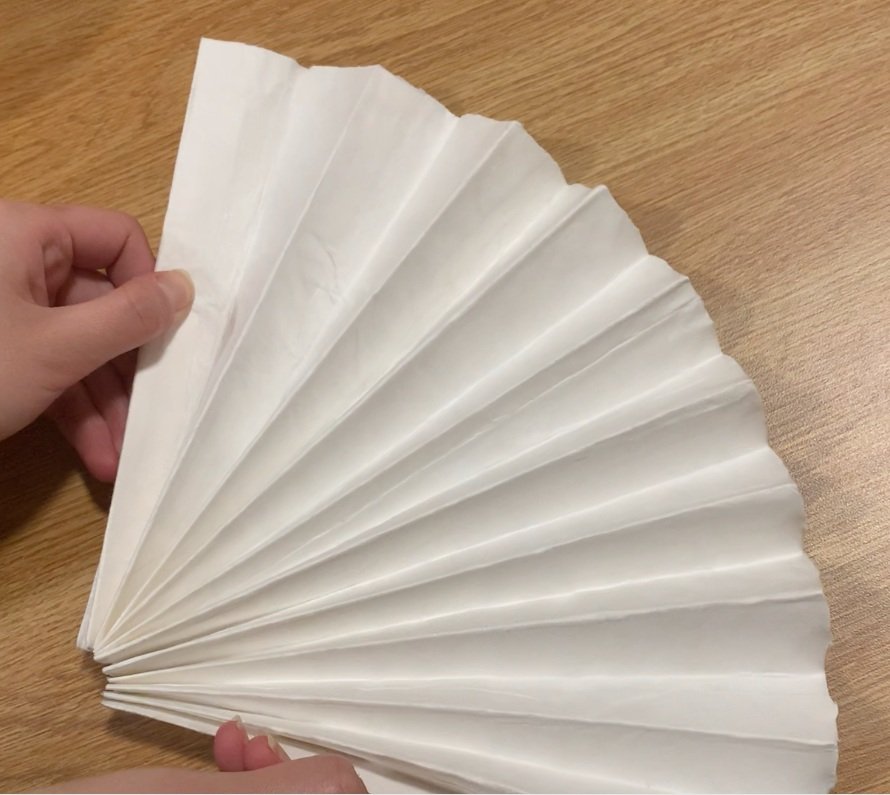

In Japan, folding fans could only be used by the aristocracy and samurai classes. Their original purpose was as an instrument for aristocrats, monks, and public officials to write on during a time when paper was a scarce commodity. These “folding fans” were actually wooden strips bound together to form a notebook that could be carried around [5]. Once the use of paper became common, the wooden strip folding fans became used as cooling devices and the first paper folding fans, “Kawahori-sen”, were created [6]. The name "kawahori” means bat and came from the resemblance of the opened folding fan to the wings of a bat [5]. These first folding fans only attached the paper to one side of the fan frame and were extremely simplistic in design as seen on the right [7].

When the fans entered China, the design was changed to paste paper on both sides of the frame and these fans with the new design were exported back to Japan. These fans were called “Karaogi” in Japan, “kara” for China, and all sensu fans adopted the Chinese technique of pasting paper on both sides [7][8].

For this project, I wanted to try recreating the Japanese sensu and the Chinese “zheshan”. The two differences I focused on with my project were the paper types and the methods of attaching the frame to the spread. I used Chinese “xuan” paper, also known as rice paper, oil paper, mulberry paper, or bamboo paper [9] for the Chinese style fan and Japanese “washi” paper for the Japanese style fan. Both types of paper are also known as simply calligraphy paper in the modern-day so I wondered if there would be any differences at all. For attaching the frame, I planned to compare the earliest forms of the folding fans (attaching one versus two sides of the paper).

“Parts of a Folding Fan” by The Fan Circle International [10]

Structure of a Fan

The folding fan has two main parts, the fan face or spread and the fan frame. The spread is made up of the leaves and is the paper portion of the fan. The frame is made up of sticks or strips with the wider, bottom half referred to as the “stick” or “fan butt” or “fan head” and the thinner, top half referred to as the “ribs” or “heart tips” [9][10]. The two sticks at the ends are known as the “backbones” and are attached directly to the surface of the paper.

There are also smaller pieces such as the fastener/rivet and tassels/pendants that attach to the end of the fans [9].

Materials

bamboo sticks (10 used for each fan frame)

(raw) xuan paper

washi paper

tapioca starch

brush

thumbtack / push-pin

scissors

ruler

string

pot

Process and Re-creation

There are no primary sources that I could find that provided written instructions on how to make a folding fan. I relied mainly on video documentation of current practitioners and a secondary source from Suzhou Shengfeng Cultural and Creative Development Co. They are an “inheritance base of the national intangible cultural heritage Su fan production skills'“, which takes the traditional handicraft "Su fan" as their “production basis” [11].

The production of folding fans involves three main processes: the making of the fan surface, the making of the ribs, and the combining of the two parts.

Fan - “Opening”

The first step to creating the paper spread of the fan is to cut an outline of the fan shape from the paper. There is no clear measurement of the dimensions for this outline and most sources only mention using previous molds or stencils. Referencing another person’s experiment with re-creating the Japanese folding fan, I spread out a completed stave to see where the fan should end and lined up the bottom of the paper with the middle of the backbones [12]. I then traced the outline of the stave onto the paper, leaving about an inch of space on all the sides. From there, I folded the paper in half to get a more symmetrical shape and cut out the fan blank. This step is called “opening” and I repeated it 10 times for each paper type to get enough sheets for two trials, each trial needing 4 blanks to be pasted together [13].

From the scraps of the fan blank cutouts, I also cut spacer strips which are placed in between the middle layers to separate the paste and leave a gap for inserting the fan bone. The length of these strips was the same as the length of the fan blanks, 21 cm, and the width was 0.7 cm, following Shengfeng’s specifications [14]. Each fan would need 10 strips for the 10 ribs so I cut 30 from each type of paper to have some backups.

Fan - “Mounting”

In order to glue the paper layers together, I had to figure out what the paste used in the videos was and how to re-create it. Initially, I found some sources mentioning “alum water” but I could not figure out how to make this water or where to find “alum” from. Instead, I looked for how Chinese paper umbrellas were put together as they are made from the same type of xuan paper. A paper umbrella manufacturing company stated they use tapioca flour to make a natural adhesive [15]. Following a YouTube tutorial on making glue from tapioca starch, I added about equal amounts of room temperature water and starch in a bowl. I mixed these two together while I boiled some more water in a pot. Once the water was boiling and over 100 degrees Fahrenheit, I slowly added water to the starch mixture and stirred as I added water. The bonds of the starch undergo a reaction with the boiled water and the texture turns from liquid to a sticky, mochi-like texture [16].

The first trial turned out really thick and was hard to mix so I thought I might have added the boiled water in too quickly to catch when the reaction happened or I was off in the starch to water ratio. For the second batch, I added in the boiled water much more slowly and added more room temperature water to the original starch mixture. It turned out more liquid in texture but still not as watery and thin as to how the paste used by the fan-makers in the videos looked. I tried adding more room temperature water and slowly the paste absorbed it and became more liquid until it was able to be dipped in and spread around.

Once I had the paste, I set up my space similar to the layout from the Suzhou workshop. Both papers were surprisingly sturdy and even though the paste wasn’t an easy application, neither paper ripped.

Translating from the Suzhou workshop video (some speech originally in Mandarin Chinese):

“Now, we’re looking at the process of making [the] fan face. There’s 2 layers here, 4 layers right? It’s done all at once?

“Yes. So mount 4 layers of paper together. This is one layer, the first layer.”

“What are these two strips glued in the middle of the layers?”

“One is the trademark/brand/watermark. The other is the standard of the materials. This is traditional. The watermark is inserted between 2 layers.” [17]

I pasted together two layers, smoothed them out as best as possible, then added the strips as best I could, equal distances apart. I was quite confused about this part of the process as the glue seeped through the strips the moment I laid them down which I was worried would happen. In the video, the woman doing the mounting only lays 2 strips down on the edges of the fan and brushes glue over them. I glued the last two layers on top of the strips and let both the spreads dry (the washi paper is on the left when hanging and on top when dried, the xuan paper vice versa).

Fan - “Folding”

The last step for the fan spread preparation is to create the folds. In both the Japan Craft video and in the images by Tachibana Mino and Ryuuryuukyo Shinsai, the folding is done with a folding mold. The paper is placed between two molds and creased by pinching the leaves together as shown in the third slide below [13][18].

![Oogi awase rokuban no uchi [Folding Paper Fans] by Ryuuryuukyo Shinsai](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/616d9ea1b28be3119da6eca7/1651108697674-J2O2IPG40507LGMQ8I5N/Oogi+Awase.jpeg)

I did not have any molds to work with so I tried to make even folds that would include one spacer strip in each fold. My first attempt ended up moving too horizontally and not following the curve of the fan. The folds made the fan look like a parallelogram as if someone had a stack of papers that had slid forward. I refolded it, focusing on keeping the folds even and following the bottom curve of the fan. This resulted in the image above which looks very similar to how it should look but the spacer strips did not end up exactly where they should have been. The folded paper should then be kept in a frame and dried so I used elastics around the folded fans to mimic the compression and setting of the folds.

Bones - “Preparation”

Screen capture from The Culture of Folding Fans in China [20]

To create the bones, bamboo is harvested and split into pieces. The individual pieces are shaved down to produce the sticks for the fan frame. The bamboo is then soaked in water and smoothed further to produce the ribs and remove splinters from the wood [19]. Often, the fan butt is carved to create detailed patterns and in modern-day, a boy carved the anime, One-Piece, into the backbone [1][20].

I chose not to re-create these steps for the sake of time and because of a lack of skill in these areas. Instead, I bought bamboo sticks that were about the right size, cut them to the length I needed, and shaved the splintered ends with the scissors, like how you sharpen a pencil with a knife.

Bones - “Boring Holes”

The next step is to make holes in the bottom of the sticks. The holes should be in the same position on every stick and the size of the hole is usually dependent on the size of the fan nail or rivet pounded through. This can be done with a drill or, in my case, a push pin or needle sharp enough to pierce through the wood [21]. In order to line up the holes, I left the pin inside one piece while I lined it up with another and began to make the hole. Once I made an indent in the next piece, I removed the first stick and finished making the hole in the second.

Bones - “Binding”

The last step to make the frame is to attach all the bones or sticks together. Most fans used fan nails or rivets like the examples images at the top of this page. I did not have the skills or the time to learn how to safely use rivets so I used string to bind the sticks as tightly as possible. Luckily, the tightest I was able to tie them was the perfect amount of tension to let the ribs fall at around 100-120 degrees (most fans open to between 90 and 180 degrees).

Combining Parts

To piece together the frame and the spread, the paper must be cut on both ends and the spaces where the fan bones are meant to be inserted should be opened up [13][18][22]. Unfortunately, what I was worried about earlier during the gluing process came true and I could not get the layers to open as they should. The glue definitely soaked through the spacer strips and left no openings to insert the bones into for the Chinese paper folding fan.

For the Japanese version, I was able to attach the ribs to the back of the fan on one side. I wasn’t able to access the same paste to attach the ribs to the paper that I had for the paper mounting so I also wasn’t able to observe any drying process for this part. I used clear scotch tape as my best option but the tape had a hard time adhering to the wood pieces and the paper.

Future Adjustments

Due to the circumstances, I was not able to do a second trial as I had originally planned and would have liked to have done. There were many parts to the process that I had to use my best guess for or try to find a similar substitute which would require many, many more trials to figure out or need an experienced fan-maker to explain. A particularly tricky part was figuring out how to leave spaces in the layers of paper so that the ribs could be inserted. The Suzhou video I followed to understand the paper mounting process showed no spacer strips so I originally had no clue how the pages would be kept apart. Even when I found another source that mentioned the spacer strips, my first trial was unsuccessful in being able to part the layers of paper once the paper dried. A possible change might be to use thicker spacer strips so that the glue would not soak through.

Another factor that might have hindered the process was the consistency of the glue I made. I think I had more starch than water since I had no measuring cups to use. I figured out that I could add more room temperature water and slowly mix the water into the paste to make it a thinner, more liquid, and more glue-like texture. However, I think the glue was still too thick as it was relatively sticky when brushing it onto the paper instead of easily gliding like in the videos. When trying to figure out why my paste was so different, I found a video on how to wet mount Chinese brush paintings onto rice paper [23]. They used a flour, alum, and water mixture that looked like the paste being used in the Suzhou workshop and matched the description of the alum mixture in the ShengFeng source [14]. Trying to recreate this specific adhesive might produce better results.

In addition, the type of brush typically used is a very specific type of brush made with goat hair (“brown broom brush”) and its main purpose is to brush alum water onto rice paper [23][14]. This brush looks like the one in the right image by Tachibana Minko and is consistent through many of the folding fan videos which helps identify that this aspect of current artisans’ practices in those videos is likely still an accurate representation of the craft [24]. It’s also interesting to think about how effective this tool is for it to have remained the same since centuries ago. Having this brush might have made the application of the paste easier and reduced the amount of wrinkles in the layered paper when it dried. I was also missing the second brush which seems to function similarly to a squeegee in getting rid of excess water and liquid from the paper which might have attributed to the wrinkling of the paper and the spacer strips not working [17].

New Understandings

I was able to gain some of my own tacit knowledge during this reconstruction process, especially in making the fan frame. By repeating the process of boring holes into the sticks so many times, I figured out that some pieces of bamboo were thinner than others (often the whiter pieces) and they were easier to push the pin into. Through trying different techniques, I discovered that the best way to make the holes was the line up the pin in a previous hole, line the bamboo sticks up, and vigorously shake the tack up and down the grain of the stick. This made it easier to start screwing in the tack to force open a hole once an indent was made. Finally, even though it was on the first try, I found that tying the string as tightly as possible actually gave me the perfect tension for the fan to open. My first try was a little looser and opened up too a bit further than the second but both still fell within the 90-180 degree range.

I also made some new observations about the primary sources by Tachibana and Shinsai when I looked at them again after finishing the process once. The woman on the right of the image by Tachibana seems to be touching and looking at a possible mold rather than an actual fan, contrary to what someone would originally think. The black fan shape seems to have an orange circle pattern painted onto it, giving the impression of it being an actual fan. However, the folded-up white fans being weighed down by a block are more likely to be the actual fans the woman is working on once you know about the existence and usage of these molds by fan-makers. The orange circle may not be a pattern and instead be another guiding mechanic. Images and designs drawn onto the fan look different on flat paper versus the folded paper and a common demonstration shows an elliptical on flat paper results in a circle on the folded paper [25]. A similar case can be seen in Shinsai’s image, where the blue fan shape is likely the mold and the two fans on the ground are the actual fans being created.

Citations

[1] Arts & Crafts Museum Hangzhou. (n.d.). The Art of Folding Fans I. Google Arts & Culture. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/the-art-of-folding-fans-i/CwLCXR2PrRNTIg

[2] Brunei Gallery, SOAS University of London. (2022). Origin of the folding fan, Brunei Gallery, SOAS, University of London. SOAS University of London (School of Oriental and African Studies). https://www.soas.ac.uk/gallery/traditionsrevised/origin-of-the-folding-fan.html

[3] Wang Yong 王勇. 1996. “Riben zheshan de qiyuan ji zai zhongguo de fangzhi” 日本摺扇的起源及在中國的仿製 [The origin of Japanese folding fans and their reproduction in China]. In Zhongri wenhua jiaoliushi daxi yishu juan 中日文化交流史大系·藝術卷 [The collection of cultural exchange history between China and Japan: Volume of art], 202–25. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Renmin Chubanshe.

[4] History and Culture of Chinese Fan, China Fan Museum. (2019, November 1). HiSoUR - Hi So You Are. https://www.hisour.com/history-and-culture-of-chinese-fan-china-fan-museum-50687/

[5] Ishizumi, K. (2015). Tracing the Origins of the Folding Fan. In D. Powers & H. Potter (Eds.), Japan Society Proceedings (2009th–2010 ed. ed., Vol. 147, pp. 76–86). The Japan Society.

[6] G. (2016, July 4). The origins of the Japanese folding fan. Japan Craft. https://japancraft.co.uk/blog/origins-of-the-japanese-folding-fan/

[7] Ohara, G. (2021, October 27). A Guide to the Traditional Japanese Craft: Kyo-Sensu Fans - BECOS - tsunaguJapan. BECOS – tsunaguJapan. https://becos.tsunagujapan.com/en/kyo-sensu-fans/

[8] Hutt, J., & Alexander, H. (1992). Ogi: A History of the Japanese Fan (Bilingual ed.). Dauphin.

[9] Qian, G. (2000). Chinese Fans: Artistry and Aesthetics (Arts of China) (First Edition). Long River Press

[10] Parts of a Folding Fan – The Fan Circle. (2022). The Fan Circle International. https://fancircleinternational.org/parts-of-a-folding-fan/

[11] 空白宣纸折扇扇面的做法_盛风苏扇. (2017, September 22). Suzhou Shengfeng Cultural and Creative Development. http://www.szfan.com/Article/kbxzzssmdz.html

[12] Joseph, L. A. (2005, March 7). Sensu: Experiments in making a folding fan. Wodefordhall. http://www.wodefordhall.com/sensu.htm

[13] Suzhou Shengfeng Cultural and Creative Development. (2017, September 22). 空白宣纸折扇扇面的做法_盛风苏扇. Shengfeng. http://www.szfan.com/Article/kbxzzssmdz.html

[14] Suzhou Shengfeng Cultural and Creative Development Co., Ltd. (2017, January 7). 白纸折扇的制作流程_盛风苏扇. Shengfeng. http://www.szfan.com/Article/bzzsdzzlc.html

[15] How To Make Paper Umbrellas | J&H. (2018). J&H Umbrella. https://jhumbrellamanufacturers.com/html_news/How-To-Make-Paper-Umbrellas-73.html

[16] Homemade Glue using Tapioca Starch. (2019, October 15). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rItsBDrrayk

[17] A Studio Tour of a Chinese Fan-Making Master Artist in Suzhou with Victoria and Henry Li. (2013b, December 11). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W0fgAfELjRg

[18] Masako, Y., Yukie, N., Miyawaki Baisenan Co., Ltd., Tomatsuya Fukui senpo, ITOTSUNE & Co.,LTD, Yoshinobu, S., Shinji, Y., & Yasuhito, Y. (n.d.). Kyō-sensu — Folding Fans from Kyoto. Google Arts & Culture. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/ky%C5%8D-sensu-%E2%80%94-folding-fans-from-kyoto-kyoto-women-s-university/igXRBsv1UYOrIA?hl=en

[19] How To Make a Chinese Fan?【Chinese craft】. (2021, August 18). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=293&v=MEbajjJx5dQ&feature=emb_logo

[20] The Culture of Folding Fans in China | 輕羅小扇. (2017, October 18). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tFbWezzMCpM

[21] Suzhou Shengfeng Cultural and Creative Development Co., Ltd. (2018, March 29). 传统纸折扇的制作工艺_盛风苏扇. ShengFeng. http://www.szfan.com/Article/ctzzsdzzgy.html

[22] Japan Craft - Making a Japanese Folding Fan. (2015, February 24). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fhgttuoimvA

[23] How to Wet Mount Chinese Brush Painting on Rice Paper a Live Workshop with Henry Li. (2012, November 3). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ii8ubo1jv1A

[24] “Fan” or “Folding Fan” Traditional crafts of Japan (illustrated with the eighteenth-century artisan prints of Tachibana Minko) by Charles A. Pomeroy

[25] Fujiko ABE, Yoshifumi OHBUCHI, Hidetoshi SAKAMOTO, Quantitative Evaluation by Production Technology and Reproduction of Traditional Folding Fan, Advanced Experimental Mechanics, 2019, 4 巻, p. 121-127, 公開日 2019/12/01, Online ISSN 2424-175X, Print ISSN 2189-4752, https://doi.org/10.11395/aem.4.0_121, https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/aem/4/0/4_121/_article/-char/ja, 抄録:

[26] Yan wei folding fan. (2016, November 1). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJTPj1v7WyE

[27] Kyoto Folding Fans and Round Fans Commercial Cooperative Association, photo: © Kuwazima Kaoru. (2017). Nakatsuke, Kyō-sensu [Photograph]. Google Arts & Culture.

![Pasting (Shengfeng [13])](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/616d9ea1b28be3119da6eca7/1651115562057-7EFLUDEAM6LZB8ZGU22V/Brush.gif)

![Spacer Strips (Shengfeng [13])](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/616d9ea1b28be3119da6eca7/1651115563715-C8478HQI9EHNP6FAFGG9/Spacer.gif)

![Hand drill (Yan wei [26])](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/616d9ea1b28be3119da6eca7/1651121700048-24O95HV58AHSZAPG74ZP/Screen+Shot+2022-04-27+at+11.54.47+PM.png)

![Cutting (Shengfeng [13])](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/616d9ea1b28be3119da6eca7/1651124900947-VVMJGA64ORPWB8Z0C21J/Cut.gif)

![Opening Holes (Japan Craft [22])](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/616d9ea1b28be3119da6eca7/1651124876277-PGFN4O192066YUC87NLW/Screen+Shot+2022-04-28+at+12.47.40+AM.png)

![Piercing (Shengfeng [13])](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/616d9ea1b28be3119da6eca7/1651124958567-T5153U1DBG614ETBR2MT/Insert.gif)

![Inserting - "Nakatsuke" ([27])](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/616d9ea1b28be3119da6eca7/1651124944187-FHXIFBGG3UCRUPK59RE5/Screen+Shot+2022-04-28+at+12.48.50+AM.png)