Jikji: Setting Down the Tiles of the Print World

An investigation of Korean Moveable Metal type Printing and Empiricism Characters carved out of beeswax. 【Read Top, down: 無一詁可當倩者】

The chances you’ve held a book in your hands before are very high. Books are all around us and as our society evolves, so do our resources to mass produce them in various different forms. Join me on an investigation into the materiality of the first moveable metal typeface of the world in Jikji from 13th century Goryeo. With various limitations in mind, I set out to explore the intangibility of mass producing the written word through a modern twist utilizing epoxy resin.

Approximately 80 years before the printing revolution that was Gutenberg’s 42-line Bible, took Europe by surprise in 1455, individuals in East Asia were already well underway through the development of the metal moveable type. While Gutenberg and the West held the title for this new lucrative printing method for a section of time, in 1955 it was discovered that Korea had actually realized metal type typography a couple of decades before with the Jikji (short for Paegun-hwasang-ch'orok-pulcho-jikji simch'e-yojŏl 백운화상초록불조직지심체요절 . This project utilizes reconstruction methodology to dig deeper into the minds of the creators of the first noted metal typeface to re-contextualize the importance of literacy and early printing culture through an understanding of the constraints and adaptation of Buddhist monks during the Goryeo period. The tangibility of knowledge through the written word was an impressive feat for humankind, however the ability to transfer several words at a time without the room for mistakes, as were commonly found through scribe’s copying by hand, revolutionized the print world.

Historical Context

For anyone outside of Korea, the Jikji an abbreviation for Paegun-hwasang-ch'orok-pulcho-jikji simch'e-yojŏl 백운화상초록불조직지심체요절, is wildly unknown. Instead, you may be more familiar with the household name Gutenberg and the famous 42-line bible that ‘revolutionized’ Europe and printing culture as we now know it. However, it is significant to recognize that several methods of printing preceded the West specifically in East Asia. While this project does not center around the technicalities of who did what first, I would like to orient us towards the idea that human beings are capable of bringing forth similar solutions from different parts of the world due to a plaguing of the same problems.

Jikji (직지)

Jikji is a Buddhist book detailing how one can follow in the steps of great Buddhist priests written by a Goryeo monk named Paekun (백운) that was printed using moveable metal type in 1377 at Heungduk-sa temple near Cheongju-si. [1] The book originally contained two volumes, volume one has not been found, but we do have 39 pages of volume two. Today, only volume two has been preserved at the National Library in France. While this portion of the Jikji is the only evidence of metal moveable type, thanks to woodblock print versions of the Jikji, scholars have been able to make out the missing characters and components. It is important to keep in mind that the Jikji is the first recorded book to be printed by metal moveable type, but that does not make it perfect. There are several instances throughout the book that demonstrate omissions of words or tilted typefaces simply because human error is natural.

Culture surrounding the Jikji

The Goryeo dynasty of the Korean peninsula encompassed the region shown in the figure below, and was active from 918 C.E to 1392 C.E. As a Buddhist state, Goryeo itself had an abundance of culture and literature produced by the Buddhist individuals of the society.[2] Their achievements throughout this period included and weren’t limited to: paper, printing, paintings, and sculptures. As a close tribute with Song China next door, Goryeo was able to engage in a wide spread culture of books and other forms of entertainment. It was during this period that we get the beginning of the coin minting system as knowledge from China gets imported in along with all of the goods from trade. It is with this knowledge and the desire to spread the word on Buddhism during a time in which the dynasty was falling that can be attributed as societal motivation for the introduction of a new printing method.

Procedure and Scope

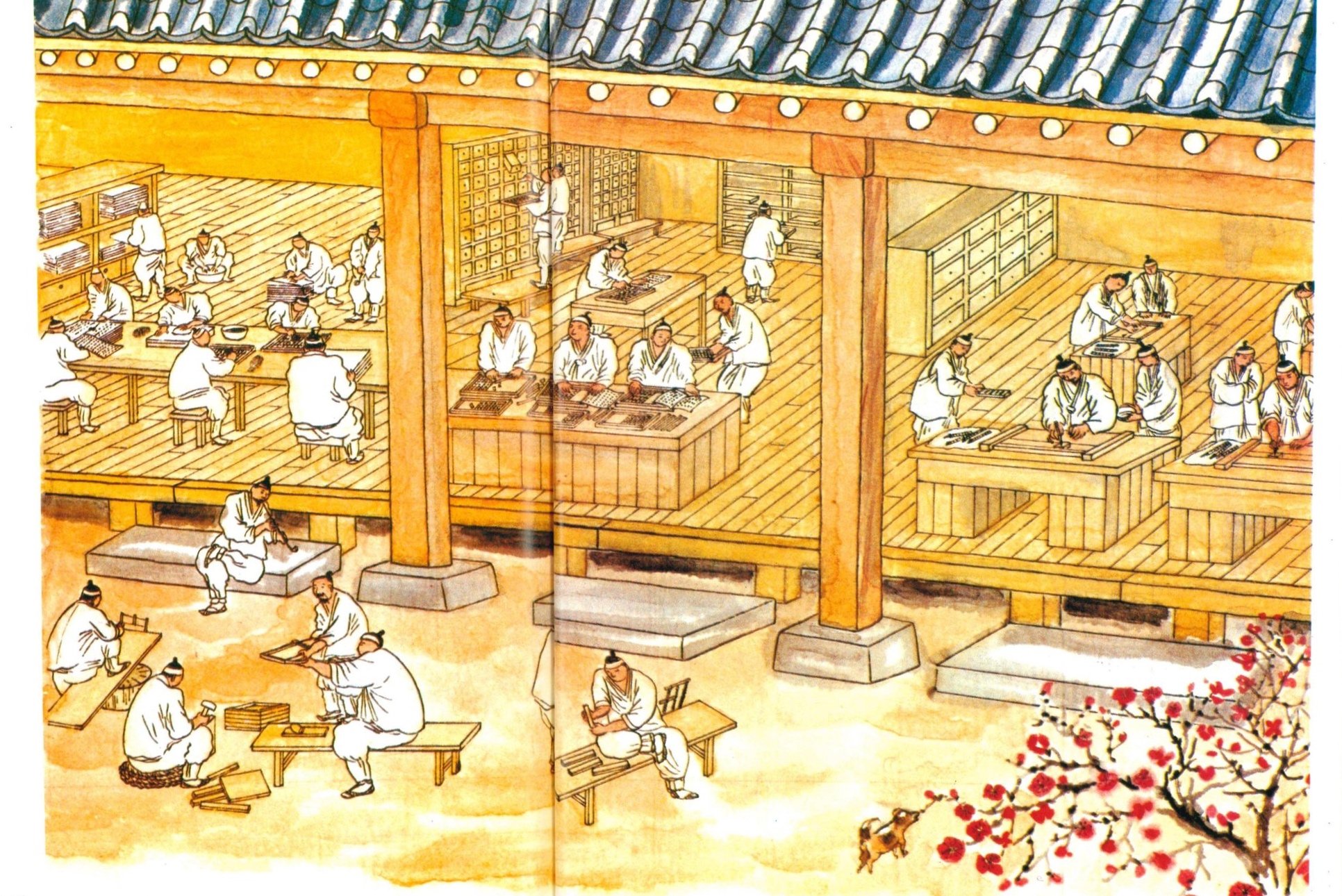

The following procedure includes my adjustments to best fit my personal knowledge and limitations but keeping consistent the integrity of the metal typeface procedure followed by master craftsman, Ŏ GukJin in 1996 [3]. If you are interested in seeing a video of the original process pictured above please visit: Google Arts & Culture.

Here are the limitations that I took into consideration during my planning process:

I am not a licensed metalworker, therefore unable to work with molten metal to create typefaces out of bronze or iron.

Instead, I will be using epoxy resin to construct my typeface prototypes.

The original procedure calls for a kaolin clay and sand mixture for the typeface molds, this however takes approximately a month to harden and dry.

Instead, I will be using liquid silicone to create reusable molds for the resin as these take 1-2 days to cure.

While a complete page recreation would have been the goal of this study, due to time and lack of skill, I have reduced the scope to encompass 30 pieces of metal moveable type from two separate pages of the Jikji. 30 characters seemed like an adequate amount to carve and obtain a mental map of the scale and knowledge that went into the craft.

30 characters were carved out of cosmetic level beeswax and 15 of these were utilized to create prototypes.

Hanji and traditional oil soot ink were made from scratch and used during the printing process. However due my project centering on the skills of the metal typeface itself, I utilized fine Hanji paper and acrylic black paint due to the texture of the resin and for fear that traditional black ink utilized for calligraphy would not stick onto the resin.

Pictured: Page 39 of the Jikji. Source: Bibliotheque nationale de France. Departement des Manuscrits. Coreen 109

Making Model Characters

1. Utilizing the National Library of France scanned version of the Jikji, select one page of reference and download directly from source.

2. Once image is downloaded, reverse the image by flipping it vertically prior to printing. This will assure that you have a mirrored version to carve the letters out.

3. Cut out strips of reference sheet.

Pictured: Carving tools and Beeswax bar base

Making Prototypes

1. Obtain Beeswax bars and cut into smaller bars with widths of 1 cm.

2. Attach strips of reference paper to each individual bar of wax.

3. Take a carving tool and cut individual characters abija 아비자 out of the wax.

4. Repeat until all of the characters are cut out.

5. Level characters by trimming smooth backside.

Pictured: Mold preparation

Casting

1. Prepare liquid silicone kit.

2. Set the wax molds in the liquid silicone and allow to cure for 24 hours.

3. After the molds have cured, remove the wax abjia and discard.

4. Inspect the molds for any missing details, correct if missing details.

5. Prepare epoxy resin according to kit instructions, careful to mix evenly and carefully.

6. Pour the prepared resin into the silicone molds to create “eomija” (어미자) characters.

7. Allow for resin to cure for 24-48 hours.

8. Once the eomija characters are cured, remove from the silicone mold, and inspect for imperfections.

9. Clean silicone from the resin eomija characters.

10. Place the completed resin types in the correct order for future use.

Pictured: Ink stamped molds

Printing

1. Obtain a flat sheet of aluminum and arrange the resin characters in the correct order.

2. Using melted beeswax, adhere each individual resin type to the flat surface.

3. Once completed, double check for correct order.

4. Acquire ink or paint and lightly brush over resin types.

5. Obtain Hanji paper and lay flat on top of resin types, using a block press down paper onto resin types and rub over the surface to imprint the paper.

6. Remove Hanji and let dry.

7. Repeat for desired copies.

Reflection on the Process

When engaging in experimentation, it is easy to focus strictly on a certain outcome or goal and forget that the true value of learning comes from the process itself. Rework methodology strives to combat this results-oriented way of thinking and re-conceptualize the in-and-outs of a procedural process. When examining the original procedure master craftsman Ŏ GukJin followed in the late 1990s to recreate the Jikji, there were several items that I was unable to use and retain in my modern day take of creating type setting prototypes, however my modern take on the moveable typeset still permitted me with my own set of grievances and in the moment jumps to action!

First I would like to start and admit that my ignorance for material properties got the best of me, but this did not mean that the experiment itself was a failure. The liquid silicone did not end up curing in the way that I was expecting in the second portion of my procedural list. This put me in a difficult situation when it came down to the second section of casting as my molds were unable to hold the resin itself, and a sticky mess was the result of my attempt to proceed as instructed. It appeared peculiar to me that the rest of the mold would cure fine but all of the sections in contact with the wax models were not able to cure even after 96 hours. With no time to attempt an additional molding trial, I cleaned the uncured resin from my wax models and attempted to use those as typefaces themselves to test whether or not they would be able to make impressions on their own. As can be seen in the gallery at the end of the page, the prints themselves were fairly legible, however the molds were rendered unusable after 2-3 imprints depending on the force of the transfer. From my rework process, I was able to note primarily on the various properties of Beeswax that made it both the perfect material for the initial portion of the process as well as not the most adequate for the latter steps discussed previously. During the carving portion of my experiment, there were several smaller details with the wax that required adaptations. For example, while wax is known to be flexible and easily imprinted, I did not foresee the ease with which the wax’s properties would vary depending on my handling. The advantages of wax are many, for example the moldability allows for intricate designs even on a smaller level that are sometimes lost to us in other material and the possibility to restart in the case of an error. However, there are a couple of disadvantages to also keep in mind. Wax’s properties change depending on the temperature of the environment, beeswax has a relatively high melting point than most other waxes at 62° C but any change in the environment can cause it to soften. In my process of carving, I experienced difficultly with the first couple of characters seen at the top of the page, due to the toughness of the wax itself. A significant amount of force was required in order to successfully carve out the exterior of the mold, in order to combat this problem, I filled a cup with hot water and dipped my metal carving tools into the water before drying and attempting to carve the wax again. The rise in temperature of the metal allowed for the wax to be imprinted easier and eliminated the issue of exerting more force and losing control for the precision of certain detailing in the mold. While one problem had be successfully resolved with an increase in contact temperature, another arose. During the carving of the latter characters, there was an increase in the ease for the carving tool to shape the wax which caused a reanalysis of the amount of force was truly needed and if I was not careful enough, I would end up taking more wax off than I needed. I hypothesize that this was a direct result from the heat transferred from my hands to the wax itself. In order to address this new issue, I would place the wax blocks into my freezer to allow for the wax’s temperature to cool prior to resuming the carving process. It took approximately 7-12 minutes for me to simply complete one 1 cm x 1 cm character.

Language is a beautiful thing, it allows us to communicate with others, convey our thoughts, and create the unthinkable. It is truly a wondrous skill that humans have developed. With language, literacy has closely followed as we turned from a society of mental skill and knowledge to one of written documentation. For the Goryeo century monks, their primary motivation of the period was to spread the word of Son Buddhism (Zen Buddhism) and to do so, they printed various books detailing the words and practices of Buddha to disseminate their word to others. It was through a combination of previous skill working with iron and bronze and the power of literacy that gave way to the first metal moveable type in the world. Once this artisanal skill is removed from its function, we can explore its impact on the rest of society. For example, these monks were well educated in written Classical Chinese and held the capacity to identify and write these characters freely, they used this skill set to translate it over to both woodblock print and moveable type print as well. Their knowledge of the characters’ properties allowed them to realize that in order to print, one would have to mirror the character prior to carving. Although this simple step can easily be overlooked (trust me, it happened to me!) and might have increased the difficultly with which the craftsmen worked in their shops, it provided all the more clarity during the end result when hundreds of pages would end up being printed and read to go out into the world instead of painstakingly writing word for word by hand.

Conclusion & Extensions for future rework

While the initial procedure and planning did not lead up to the expected goal, this experimentation was nothing short of a success. It is true as I stated in the previous section that my naivety left me without an expected end result. However, I was still able to check the success of my carving through other means. This project has been a wonderful learning experience in terms of combating personal assumptions and confidences that ultimately led to small hiccups along the way. Literacy and language are both still ever present in today’s world as we learn to create new ways to disseminate our thoughts with the new world. In our contemporary, we are currently used to writing and typing on our electronic devices and utilizing the internet to transfer information from one source to an other. The questions are still the same, how do we facilitate the process for spreading knowledge? What can we do to minimize the errors and mistakes? What method is the most cost-effective? We may be living in a different time with new technologies, however, we as humans battle some of the same obstacles just in different forms.

In the near future, it would be interesting to test the materiality of the wax against other substances and their reactions in terms of creating the best fit molds. Even during the initial stages of the procedural process during the Goryeo period, craftsmen combated the rising issues of durability, resource availability, and several environmental factors when creating their metal typefaces. Although I am currently centuries removed from the original process with the use of new resources and new environments, the problems and human drive to solve problems has been transferable.

Below I list a couple of ways to reexamine this project with modern day substitutions to the original procedure:

Instead of using liquid silicone to create molds, a polymer clay could be adapted in order to obtain the waxes shape and detail.

Possible limitations: the wax is sensitive to the touch and the shape is easily distorted if too much pressure is applied.

Wooden abija characters could used instead of wax, Balsa wood is relatively easy to carve and it could be interesting to see how this pairs up with liquid silicone.

Possible limitations: not as flexible as the wax when it comes for rooms of error

If all else, a metalworks class can be taken to develop metalworking skills and attempt at a full scale reworking!

Possible limitations: this would take an extensive amount of resources and time.

Sources:

[1] Traces of Jikji and Korean Movable Metal Types : In Commemoration of the 10th Anniversary. Cheongju Early Printing Museum. Cheongju City [South Korea]: Cheongju Early Printing Museum, 2003.

[2] Cartwright, Mark. "Goryeo." World History Encyclopedia. Last modified October 17, 2016. https://www.worldhistory.org/Goryeo/.

[3] Son, Po-gi. Early Korean Printing. Korean Overseas Information Service. Seoul, Korea.

[4] Cheongju Early Printing Museum. “How to Make Movable Metal Type of Goryeo: Beeswax Casting.” Google Arts & Culture. Google. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/CgVRF4hXMD9vIQ?hl=en.

Additional Sources:

백운화상초록불조직지심체요절. 白雲和尙抄錄佛祖直指心體要節. National Library of France. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52513236c

Park Moon-Year. “A Study on the Type Casting, Setting and Printing Method of "Buljo-Jikji-Simche-Yojeol"” in: Gutenberg-Jahrbuch | Gutenberg-Jahrbuch - 79 | Koreanischer Buchdruck (32 - 46)

UNESCO nomination form: Baegun hwasang chorok buljo jikji simche yojeol (vol.II), the second volume of "Anthology of Great Buddhist Priests' Zen Teachings" 2000.