Gochujang: An Ancient and Modern Fundamental Condiment

Background

Describing Gochujang

Korean red peppers.

© Image created by Perplexing. Creative Commons License. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Korean_chili_pepper_drying.jpg [7]

Meju drying.

https://pixabay.com/photos/korean-food-meju-miso-441467/ [16]

Gochujang (kochujang) is a condiment originating from Korea. It is widely considered one of the three most important condiments of Korean cuisine along with kanjang and toenjang [11]. The word “gochujang” is a compound of “gochu” and “jang.” The term “jang” refers to a family of Korean sauces and pastes made from fermented soybeans [2]. When making gochujang, these soybeans are commonly fermented in the form of meju – bricks of mashed-up soybeans [2]. The term “gochu” refers to a Korean variety of red pepper that gives gochujang a spicy but slightly sweet flavor as well as its bright red color [1]. Rice is another common ingredient in Gochujang. Some less common ingredients that are sometimes added are barley, jujubes, wheat flour, red beans, meat powder, honey, and sweet potatoes [3][11].

History of Gochujang

Some have theorized that red pepper was introduced to Korea during the sixteenth century after the Japanese invasion of Korea [1][6][11]. This would suggest that gochujang was not in use before the sixteenth century. However, based on records of Korean gochu production and soybean fermentation from as far back as 37 BCE, it has been inferred that gochujang may have been first used over 2000 years ago [1][2]. Despite the condiment’s long history, it is still extremely popular today. Gochujang has been used for a wide variety of dishes and can be found in stores all over the world [11]. Gochujang is so widely known that some fast-food restaurants are adding the condiment to their menus [10].

Shake Shack advertisement promoting gochujang condiment

https://twitter.com/shakeshack/status/1346498511328731141/photo/1 [10]

My Project

My favorite foods incorporate strongly flavored sauces. As a result of this, when I found out about gochujang, I was very interested in how it would taste considering that it is a condiment known for its strong flavor. I was especially curious to see how such a sauce would have evolved over time. Thus I chose to center my rework project around gochujang. For my rework, I used an old recipe for gochujang that was recorded during the late Chosŏn period [4]. The recipe I used was found in the book Kyuhap ch’ongsŏ (Home encyclopedia for women in the inner chamber) written by Yi Pinghŏgak (Madame Yi) (1759–1824) – one of the earliest woman writers in Korea [4]. Madame Yi’s book also includes a few details on making the meju required to make gochujang as well as a recipe for making Cang Pokki (a type of stir-fry) that uses gochujang. I decided to incorporate these into my rework project as well.

Rework

Recipes

The original text containing the recipe that I followed is written in Korean. I cannot read Korean so I used a translated version of the text.

Measurements:

1 mal -> 4.5 cups

1 toe -> 0.45 cups

1 mal = 18 liters

1 toe = 1.8 liters

Adding up the ammounts of the ingredients listed in the recipe, the recipe seems to suggest making over 30 liters of gochujang or about 8 gallons. I only needed enough to make a few different variations so I greatly scaled down the recipe. I used the conversion 1 liter -> ¼ cup.

Ingredients

Chang Pokki:

-Beef

-Sesame Oil

-Ginger

-Green Onions

-Gochujang

-Honey

-Sesame Seeds

Optional:

-Glutinous Rice

-Green Onion garnish

Meju:

-Soybeans

-Glutinous Rice

Gochujang:

-Salt

-Water

-Glutinous Rice

-Red Pepper Powder

-Meju Powder

Optional:

-Jujubes

-Honey

-Meat powder

Process

Making Meju

First I soaked soybeans for about 4 hours and simmered them for about 5 hours so that their husks would come off and so that the beans would be easy to mash. Next, I pounded glutinous rice into small pieces and steamed this rice for about 10 minutes. After the rice finished steaming, I mashed the cooked rice into the soybeans. Then I shaped handfuls of this compound into bricks. I had enough for three handful-sized bricks. I split one of the bricks into many smaller bricks of various sizes as an experiment. I placed some moldy blueberries next to one brick of meju in an attempt to provide microorganisms for fermentation. I placed these meju bricks on paper plates and put them into cardboard boxes to let them ferment and dry out. After the first week, a white mold was growing on the meju and they smelled like used sneakers. After the second week, the white mold was mostly gone and they smelled like peanut butter.

Fermenting Meju

Making Gochujang

First I steamed glutinous rice. While this rice steamed, I put store-bought meju powder into a large bowl. I poured water into a large bowl and added salt until the salt was slow to dissolve. Then I stirred this saltwater into the bowl of meju powder. Next, I stirred Korean red pepper powder into the mixture. When the rice finished steaming, I stirred the rice into the bowl and added water to keep the mixture’s consistency close to that of porridge. At this stage, the gochujang had an orange color rather than its signature bright red color. The recipe calls for adding salt and red pepper power “to suit one’s taste.” My gochujang tasted quite salty so I didn’t add any more salt. I couldn’t taste the red pepper powder at all so I added a lot of red pepper powder.

Optional:

I put part of my gochujang into a separate container and added crushed jujubes, honey, and a bit of dried meat powder.

Reworked Gochujang

Making Chang Pokki

First I cut up beef, green onion whites, and ginger into small pieces. Then I mixed the beef with gochujang and added the green onion whites and ginger. I fried this up in sesame oil. I sprinkled sesame seeds onto the stir fry and stirred it with rice. I made one batch with store-bought gochujang and one with the gochujang that I made. I also made a batch using my gochujang along with ground beef rather than with sliced beef.

Reworked Chang Pokki

Reflection

How Things Tasted

The store-bought gochujang tasted too sweet while the gochujang I made tasted too salty and was a bit dry. The addition of meat powder made the gochujang taste awful. Jujubes and honey were good additions to my gochujang. Adding more red pepper powder also made my gochujang taste better as it increased its strong spicy flavor while also reducing the proportion of salt to other ingredients.

The Chang Pokki was decent with both the store-bought gochujang and the gochujang I made.

I am apprehensive about trying my meju as I am not confident that the mold that grew on my meju is innocuous.

Whether or not everything tasted good, I still enjoyed learning about and making gochujang. If I had added less salt to my gochujang, I can imagine that it would have tasted a lot better. I may try to make gochujang again.

Areas For Improvement

Meju

I ran into a few issues when trying to rework meju. Meju typically takes much longer than two weeks to prepare. This prevented me from using my meju to make gochujang.

Another issue I ran into had to do with interpreting the recipe for making meju. I was not sure what Madame Yi’s recipe meant by “pound two toe (3.6 liters) of rice, make sediment” [3]. I consulted my professor on this and he informed me that the untranslated recipe calls for pounding rice and making steamed rice cake (paeksŏlgi) [12]. I figured that my mashed-up and steamed rice was probably not too different from steamed rice cake and I did not have time to cook more soybeans so I did not attempt to make meju with paeksŏlgi. If someone were to rework this recipe in the future, they may want to try this.

Another big issue is that I did not have access to rice straw. Rice straw is widely considered to be important for providing microorganisms to meju that are helpful for fermentation [13]. I used paper plates as a substitute for rice straw. I put moldy blueberries on the paper plate of one of the meju bricks in an attempt to provide microorganisms in case a paper plate was not sufficient. Fortunately, mold did grow on my meju bricks. After a week, the mold was white but after two weeks, the white mold was mostly gone and instead replaced with fuzzy gray mold. Most pictures of meju that I have seen show the meju with either no mold or with white mold so I am not confident that the right kinds of microorganisms ended up growing on my meju.

Gochujang

Overly-Salted Water

The recipe I followed says “Put four toe (7.2 liters) of salt in good water per one mal of powdered meju and mix well.” [3]. I was unsure if this meant that 7.2 liters of salt was to be added or that 7.2 liters of salt water was to be added. I chose the latter of these two interpretations. I poured a fixed amount of water and added salt to the water until the salt no longer dissolved quickly. I suspect that this is not what was intended by Madame Yi because the end of the recipe suggests that more salt could be added based on one's preference but my meju already tasted extremely salty. Considering that a later step of the recipe calls for adding water until the consistency is like porridge, Madame Yi might have intended for the person following the recipe to add however much water was needed for a porridge-like consistency in this earlier step as well. If I were to follow this recipe again, I would interpret the 7.2 liters as referring to the amount of salt to add rather than the amount of water to add and see how that works out.

Chang Pokki

The main issue I had with my stir fry was that I wasn’t sure how to interpret the phrase “sifted meat” in the translated recipe. The phrase “sifted meat” makes it seem like the meat should be put through a sieve of some sort. The gochujang recipe already called for optional meat powder so I decided that adding meat powder would not make much sense. I do not think that any other kind of meat would easily go through a sieve. I thus chose to interpret it as “slice up the meat into small slices.” I later consulted my professor on what might be a good substitute for “sifted meat” and he informed me that modern recipes for beef and gochujang stir-frys often use minced meat [12]. This is what led me to create another batch of Chang Pokki but with minced meat instead of finely-sliced meat. The problems with my reworked gochujang carried over to my reworked Chang Pokki. The final product was too sweet with the store-bought gochujang while it was too salty and a bit dry with my reworked gochujang.

Chang Pokki with Sliced Beef.

On the left: Too sweet. On the right: Too salty and a bit dry.

Chang Pokki with Minced Beef.

Observations

The Clarity of Madame Yi’s Book

In the preface to her book, Madame Yi wrote “If once this book is open and read, the meaning should be understood and easily followed.” [3]. Ironically, Madame Yi’s recipes are extremely confusing. Amounts of various ingredients are not always given along with units and some processes are glossed over or explained with little clarity. Madame Yi also assumes that the reader knows what various foods like “sifted meat” and “adlay porridge” are. This makes more sense if one considers that Madame Yi may not have intended for a general audience to easily understand her work. Madame Yi also wrote in her preface, “a good memory is not as good as poor writing. How could this knowledge be helpful if not recorded for the time when I will [inevitably] forget?” [3]. It is possible that Madame Yi’s text was meant to be a memory aid more so than a fully detailed cookbook that anyone could pick up and use. Madame Yi further writes “I give this book to the daughters and daughters-in-law of the house.” [3]. This further supports the argument that Madame Yi’s book was not intended to be fully understood by a broad audience. It seems plausible that Madame Yi would teach her younger relatives how to make the foods listed in her book. These younger relatives would have gained the tacit knowledge required to make these foods both by learning specifically from Madame Yi and by learning the general cooking methods of the time period. In this way, the book would serve as a memory aid for them and would be easily understood by them. At the same time, I struggled to follow the recipes as I am not familiar with the cooking methods of the past nor the specific cooking methods employed by Madame Yi.

The Portion Size

When making gochujang, I found that the portions that Madame Yi suggests in her recipe are huge. Her measurements are in mals and hops. According to the translated recipe, these units are similar to 18 liters and 1 liter respectively. Combining the volumes of 7.2 liters of salt water, 18 liters of powdered meju, one liter of red pepper powder, and 3.6 liters of glutinous rice along with optional jujubes, honey, meat powder, and extra water to keep the consistency of the mixture constant, the recipe seems to call for the production of over 30 liters of gochujang or approximately eight gallons. From this, one would likely guess that Madame Yi intended for her gochujang recipe to be made in large amounts and then stored without spoiling or that she intended for it to be used to serve a large number of people at once. The former seems most likely. According to Pettid, families stored large quantities of gochujang as it was vital for flavoring a huge variety of dishes [11]. Pettid also notes that gochujang is often allowed to ferment once it has been made. [11]. Thus it would make sense that huge batches would be made at once as gochujang was needed frequently and would not spoil but rather ferment, becoming better with time. Strangely, Madame Yi does not mention anything about allowing gochujang to ferment. This may have been assumed to be obvious to the reader.

The Amount of Red Pepper Powder

Something I find particularly interesting about Madame Yi’s recipe for gochujang is that it calls for about 18 liters of meju powder and only about one liter of red pepper powder. The bag of meju powder that I bought from the store has a recipe for gochujang that calls for two pounds of meju powder and four pounds of red pepper powder. This would be a 1:2 ratio in favor of there being more red pepper powder than meju powder [8]. The 18:1 ratio recommended by Madame Yi is what I made my gochujang with at first. This ended up giving my gochujang an orange-brown color rather than the red color that is characteristic of modern gochujang (see the below images for the sake of comparison). As I mentioned above, when I tasted my orange-colored gochujang, the flavor of the red pepper powder was barely detectable at all. One could attribute this to a number of possibilities.

My first guess was that the translation I was using may be incorrect. After consulting my professor, he informed me that the measurements in the original recipe were no different from the translated recipe [12]. Perhaps gochujang was different in the past and preferences for spicier gochujang developed over time until it became what it is today. This seems implausible considering that the word gochujang comes from the word “gochu.” Red pepper is the defining ingredient of the condiment but my reworked gochujang didn’t taste like red pepper at all. I would probably call my orange-brown-colored gochujang soybean paste rather than red pepper paste. Of course, there is the possibility that Madame Yi just made a mistake when writing the recipe down. Another possibility is that she intentionally low-balled the amount of red pepper powder required in the recipe so that whoever was following the recipe could add more as they desired. The recipe does say “The amount of salt and red pepper powder can be regulated to suit one’s taste.” [3]. I added a lot more red pepper powder than was required to my gochujang, coming closer to the 1:2 ratio of meju powder to red pepper powder recommended by the packaging of the store-bought meju powder.

Madame Yi’s Gochujang recipe made without adding red pepper powder to suit my taste. The mixture has a slight orange color.

Photo of modern gochujang. The mixture has a bright red color.

© Photo taken by Jamie Frater. Creative Commons License. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/ https://www.flickr.com/photos/jfrater/6429406657 [9]

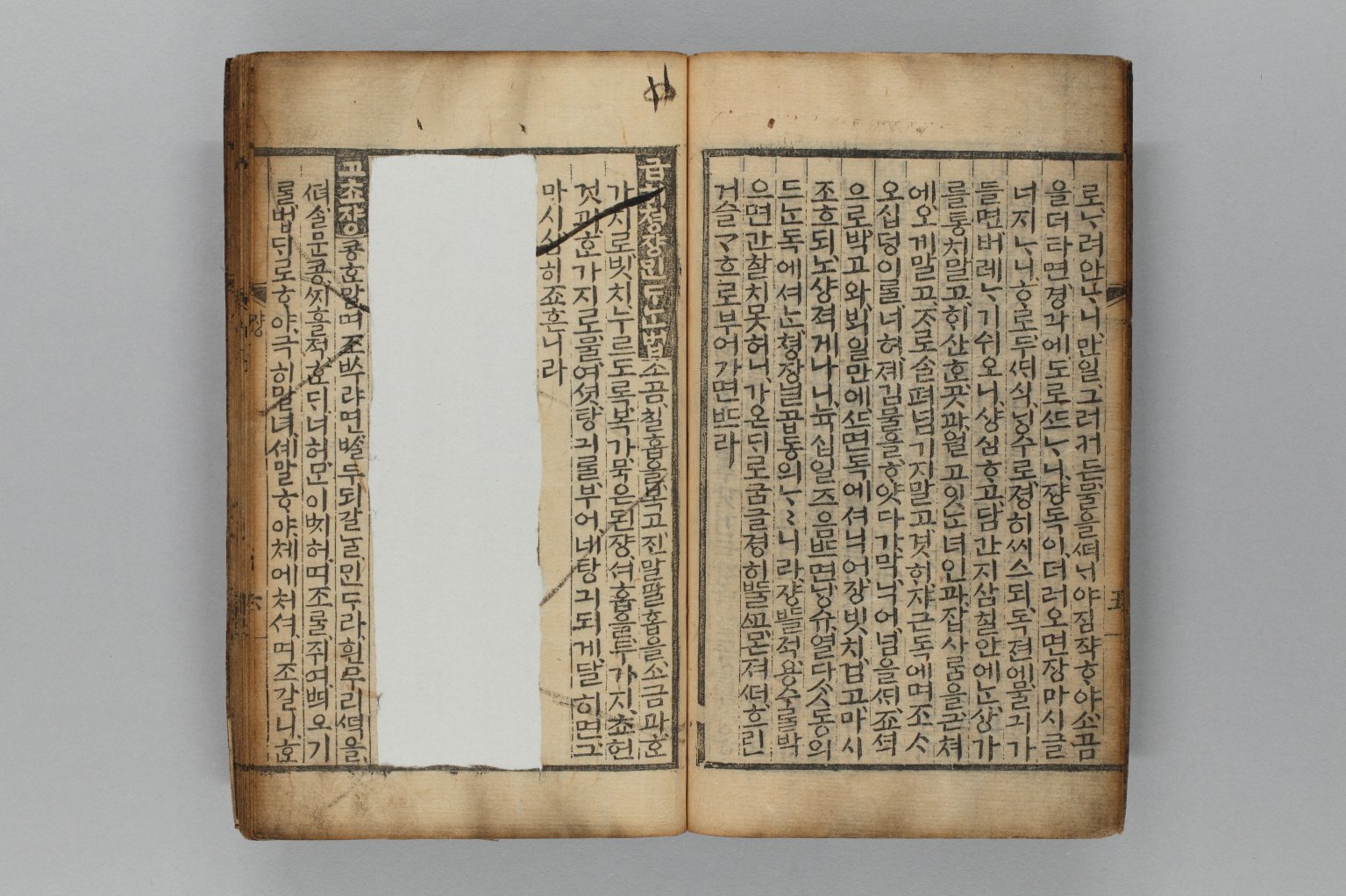

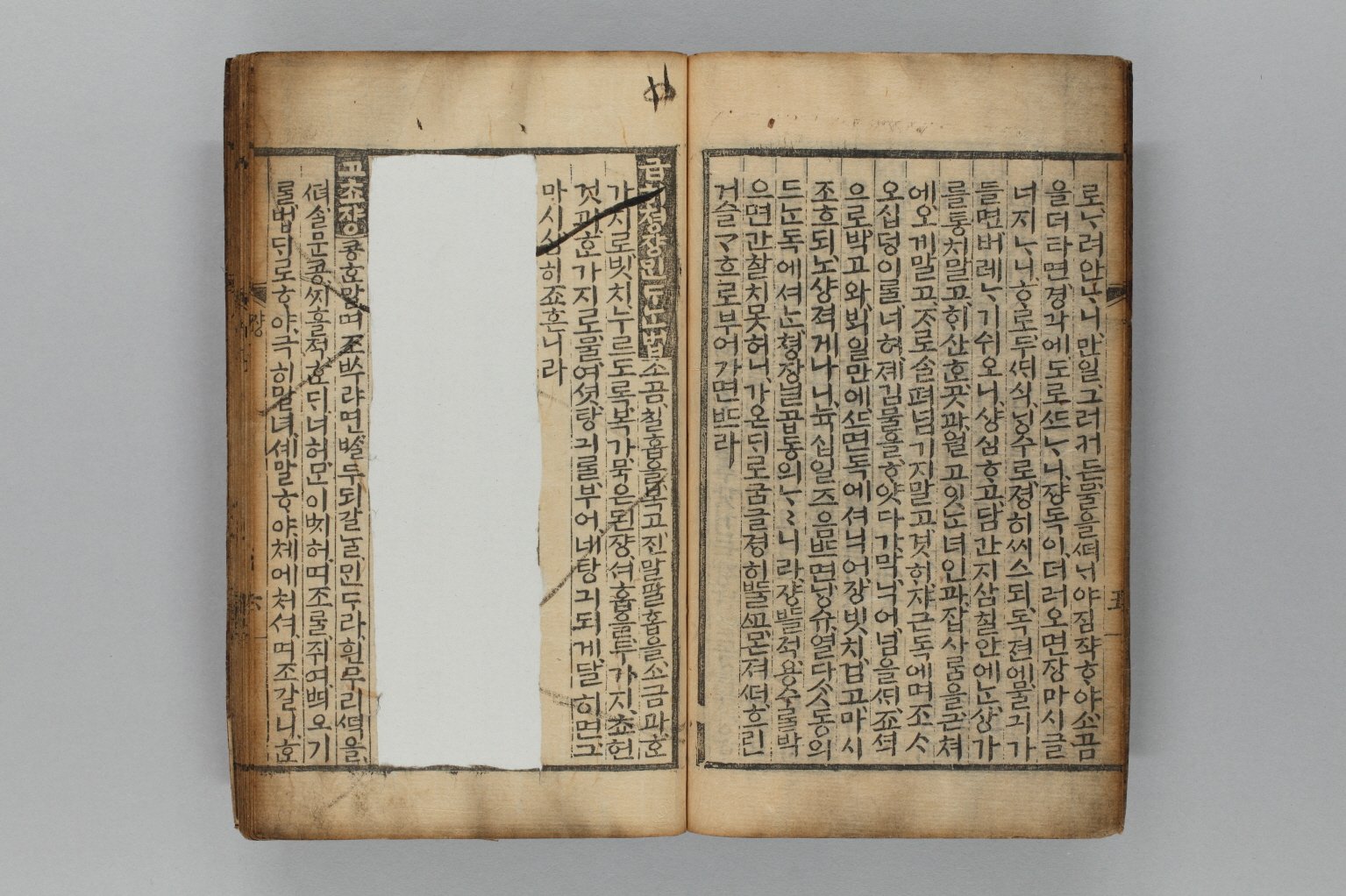

The Original Text

The physical state of the untranslated version of Madame Yi’s book that I used is intriguing. Quite a few passages are crossed out with ink including the recipe for gochujang. Some passages are also covered with white slips of what appears to be hanji paper. Perhaps the owner of this copy of the book chose to cross out sections that contained errors or perhaps the owner decided to cross out the recipes that they disliked. These possibilities could make sense considering that the book’s recipe for gochujang calls for some bizarre ratios of ingredients. The white slips of paper were clearly added after the passages were already crossed out with ink as they cover up the ink of the cross-outs. The paper slips were probably added long after the book was created considering that they do not appear to be yellowed at all. Hanji paper is known for being durable. Perhaps the paper slips were added to mend damage done to the book.

Recipe For Gochujang

From the Ogura Bunko collection at Tokyo University [5]

The Evolution of Gochujang

The ingredients used in the various gochujang recipes I have read seem to differ.

Madame Yi’s gochujang recipe calls for salt, water, glutinous rice, red pepper powder, and meju powder[3]. The recipe on the back of the store-bought meju powder bag calls for water, meju powder, glutinous rice powder, red pepper powder, malt, and salt [8]. The ingredients on the store-bought gochujang container are “wheat flour, corn syrup, mixed seasoning(red pepper powder, water, salt, garlic, onion), water, salt, red pepper powder, fermented ethyl alcohol, hydrolyzed vegetable protein(wheat)” [15]. Listed in order of abundance.

Madame Yi’s recipe for making gochujang and the modern recipe for making homemade gochujang include similar ingredients. Both require salt, water, red pepper powder, and meju powder. While Madame Yi’s recipe calls for regular glutinous rice, the modern recipe calls for glutinous rice powder and additionally requires malt. Glutinous rice powder is likely used over regular glutinous rice to ensure that no grains of rice are present in the final product. Malt is probably included to help with the fermentation process used in the recipe. The biggest difference between the recipes is the ratio of meju powder to red pepper powder being 1:2 for the modern recipe as opposed to 18:1 for Madame Yi’s recipe as mentioned previously. Considering that Madame Yi’s recipe was likely meant to incorporate more red pepper powder than it requires, these recipes aren’t all that different. These modern alterations to the old recipe seem like they were likely implemented to better the quality of the gochujang. I would be interested in trying to follow this recipe to see how the resulting gochujang tastes.

On the other hand, the store-bought gochujang is quite different from Madame Yi’s recipe. The shared ingredients are red pepper powder, water, and salt. The store-bought gochujang does not contain rice in any form nor soybeans in any form. It appears that rice was substituted for wheat while meju powder was substituted for fermented ethyl alcohol. What is especially odd about the store-bought gochujang is that its second most abundant ingredient is corn syrup. This was likely responsible for the overly sweet flavor of the store-bought gochujang. These recipe alterations were likely made for the sake of cheap, consistent, and quick production.

For a number of reasons, I suspect that the store-bought style of gochujang is what people are generally accustomed to today. First, factory-made gochujang was stocked in large quantities and sold in large quantities at the stores where I got my ingredients. Second, using store-bought gochujang is much more convenient as making gochujang takes effort to make and it takes a lot of time for fermentation to run its course. Furthermore, people may be concerned about the safety of eating foods that they fermented themselves. I was certainly worried about this when making meju.

Citations

[1] Kwon, Dae Young, et al. “History of Korean Gochu, Gochujang, and Kimchi.” Journal of Ethnic Foods, vol. 1, no. 1, 2014, pp. 3–7., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jef.2014.11.003.

[2] Shin, Donghwa, and Doyoun Jeong. “Korean Traditional Fermented Soybean Products: Jang.” Journal of Ethnic Foods, vol. 2, no. 1, 2015, pp. 2–7., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jef.2015.02.002.

[3] Pettid, Michael J., and Kil Cha. The Encyclopedia of Daily Life: A Woman’s Guide to Living in Late-Chosŏn Korea. University of Hawai’i Press, 2021, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1bn9jks. Accessed 26 Apr. 2022.

[4] Sang-ho, Ro. “Cookbooks and Female Writers in Late Chosŏn Korea.” Seoul Journal of Korean Studies, vol. 29, no. 1, 2016, pp. 133–157., https://doi.org/10.1353/seo.2016.0000.

[5] Pinghŏgak, Yi. Kyuhap ch’ongsŏ. 1869. Tokyo University Ogura Bunko collection.

[6] Cwiertka, Katarzyna J. “The Soy Sauce Industry in Korea: Scrutinising the Legacy of Japanese Colonialism.” Asian Studies Review, vol. 30, no. 4, 2006, pp. 389–410., https://doi.org/10.1080/10357820601044950.

[7] Perplexing. “Korean Chili Pepper Drying.” Wikimedia Commons, 2007, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Korean_chili_pepper_drying.jpg. Accessed 25 Apr. 2022.

[8] ASSI. Meju Garzuru Soy Bean Powder. Recipe for making Hot pepper paste.

[9] Frater, Jamie. “Gochujang.” Flickr, 2011, https://www.flickr.com/photos/jfrater/6429406657. Accessed 25 Apr. 2022.

[10] Shake Shack [@shakeshack]. Twitter, Twitter, 5 Jan. 2021, https://twitter.com/shakeshack/status/1346498511328731141.

[11] Pettid, Michael J. Korean Cuisine: An Illustrated History. Reaktion Books, 2008.

[12] Kang, Hyeok Hweon. Apr. 2022.

[14] Kim, Dae-Ho, et al. “Fungal Diversity of Rice Straw for Meju Fermentation.” Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, vol. 23, no. 12, 2013, pp. 1654–1663., https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1307.07071.

[15] Wang Globalnet. Ingredients Label of Go Chu Jang Hot Pepper Paste. Korea.

[16] Misoo, Park. “Five Bricks of Meju Hanging to Dry.” Pixabay, 2014, https://pixabay.com/photos/korean-food-meju-miso-441467/. Accessed 25 Apr. 2022.