Maedeup: A Meditation on Knots and the Ties that Bind

The Boy Scouts have taught youth across America the functional purposes of knots, but we must look to East Asia, Korea in specific, to examine their aesthetic value.

Maedeup (매듭) is a cultural Korean craft centered around making knots out of a woven thread called Dahoe (다회). Then, the knots are finished by adding one or more tassels called Sul (술). These knots are then used for a multitude of religious, social, and decorative purposes. However, as the role of Maedeup in Korean culture has changed drastically over time, before we can delve into its usage, we must first examine the history of Maedeup to allow us to understand its current place in the cultural zeitgeist.

Background:

Maedeup’s popularity began with the Three Kingdoms period but its origins are found in the Neolithic period. Examining the tools of that time, specifically stonecutters, shows that “rope was tied to these devices”, meaning that knots were present (Kim 2016, 8-9). Once we enter the Three Kingdoms period, we see the first example of aesthetic Maedeup. A painting from in the Goguryeo Dynasty, titled “Nobleman”, painted in 357 AD portrays a couple with Maedeup decorating the scene around them (Figure 1). In another painting, titled “Dancers”, a group is portrayed wearing belts of Gwangdahoe (광다회), a wide and flat version of Dahoe (Figure 2). In the Joseon Dynasty, Maedeup began to grow in popularity moving from just the royals to include commoners (Kim 2016, 24). This popularity grew until the craft became commercialized. Unfortunately, as the Japanese occupation occurred, the craft of Maedeup was almost wiped from the country.

Fig. 1 “Nobleman.” Mural in Anak Tomb No.3 Goguryeo period, 357AD. Hwanghae-do Province.

Fig. 2 “Dancers.” Mural in Muyong Tomb, 5th-6th Century. Jian, Jilin Province, China.

The process of making Maedeup starts with the dying of silk thread. Certain colors, specifically red, blue, yellow, black, and white, represent the cosmos and when combined, form an artistic yin and yang relationship. The silk threads are boiled to make them soft and then they are dyed with natural dyes including oyster shells, plum juice, and many others. This dyeing process is repeated multiple times to ensure that the color is set. Next, the cord goes through a process called dahoechinda (다회친다), or the weaving of the cord. There are two main types of cord, Dongdahoe (동다회), a rounded cord, and Gwangdahoe (광다회), a wide flattened cord. The thickness of the woven cord depends on the number of threads used, varying from four to thirty-six. Typically waistbands are made from thick Gwangdahoe, knife bands from thin gwangdahoe, and other maedeup is made from Dongdahoe. After being woven, the dahoe is made into knots, which usually take their form from the natural world. For example, the gukhwa (국화) knot is shaped like a chrysanthemum, the jamjari (잠자리) knot is shaped like a dragonfly, and saengjjok (생쪽) knot is shaped like ginger. Lastly, the tassel is attached which helps “enhance the structural beauty formed by the cord and the knots.” Different tassels were used for different implementations of Maedeup. (Kim 2016, 138-179).

Maedeup uses can be defined into three main categories: royal, religious, and fashion. In the royal category, Maedeup has been been used on seals, portraits, swords, batons, and banners. As red represented “power over all living things”, it was used for the royal seal and many other royal Maedeup implementations. As for religious uses, religious Maedeup was traditionally found in Buddhist temples. It was used to ornament everything from decorative pouches to palanquins that carried the Buddha. Finally, Maedeup had a special role in fashion especially in the norigae (노리개), a piece traditionally worn by women. The norigae, which came with one to three tassels, typically included a few knots and some other ornaments. They were an important part of the time’s fashion with different occasions requiring different kinds of norigae (Kim 2016, 45-138).

Fig 3. Norigae, Pendant with Three-part Maedeup and Ornaments, 1986, National Museum of Korea, Yongsan-gu, Seoul, South Korea.

Sources:

My primary tool in attempting to recreate Maedeup is Maedeup: The Art of Traditional Korean Knots, a book by Kim Hee-Jin. Kim is the founder of multiple institutions such as the Kim Hee-Jin Traditional Craft institute and the Korea Maedeup Institute. She also is a designated master in the field of Maedeup, “a state-designated Important Intangible cultural asset,” and has even created Maedeup for the Pope. She came into the field during the early 20th century when Maedeup began to die out as a craft due to “devastating social turmoil” (Kim 2016, 1). Her book is a combination of paintings, artifacts, and analyses meant to both discuss the history of Maedeup and give some insight into actual craft practices with the hope of preserving Maedeup for generations to come. She lays out how to create Maedeup, with pictures and examples, from the dyeing and weaving of the cord through making the knots and tassels.

Kim’s credentials make her almost a governing body on the topic Maedeup, but a picture is worth 1000 words, and a video is worth even more. So, as a secondary tool, I will be utilizing a video by K-HERITAGE.TV called Maedeupjang, the craftwork which completes the beautifulness. This video features a Maedeupjang (매듭장), a master of Maedeup, and walks through the process of dyeing silk thread, weaving it into Dahoe, making the knots of Maedeup, and creating the tassels, Sul. This master follows processes that coincide directly with those laid out in Kim’s book. When the master is weaving the dahoe, she uses a machine similar to Kim Hee-Jin’s Eight Strand Frame and her tassel frame is almost identical to the one in Kim’s book (Kim 2016, 150, 169). This forms an artisanal basis from which we can conclude that both sources are credible as to their discussion on the craft of Maedeup.

Outside of the artisanal basis, academic research can be utilized to both widen the scope of our investigation as well as provide further confirmation as to the validity of our other sources. One such study is on the distribution of Dahoejangs (다회장), masters of making dahoe, in the Joseon Dynasty. This study reveals that “out of 2841 craftsmen… 1 of them were Dahoejangs,” meaning that it was on the rarer end as a career (Park 2014, 1). The continuation of this proportion of artisans perfectly sets the stage for the disappearance of Maedeup as a craft, as, towards the end of the Joseon Dynasty, Maedeup became commercialized. When combined with the relatively few artisans who knew the necessary skills to make dahoe, the cultural suppression brought on by the Japanese occupation of Korea was able to easily shrink and almost destroy the craft, despite the popularity of Maedeup among the general Korean populace.

Experiment:

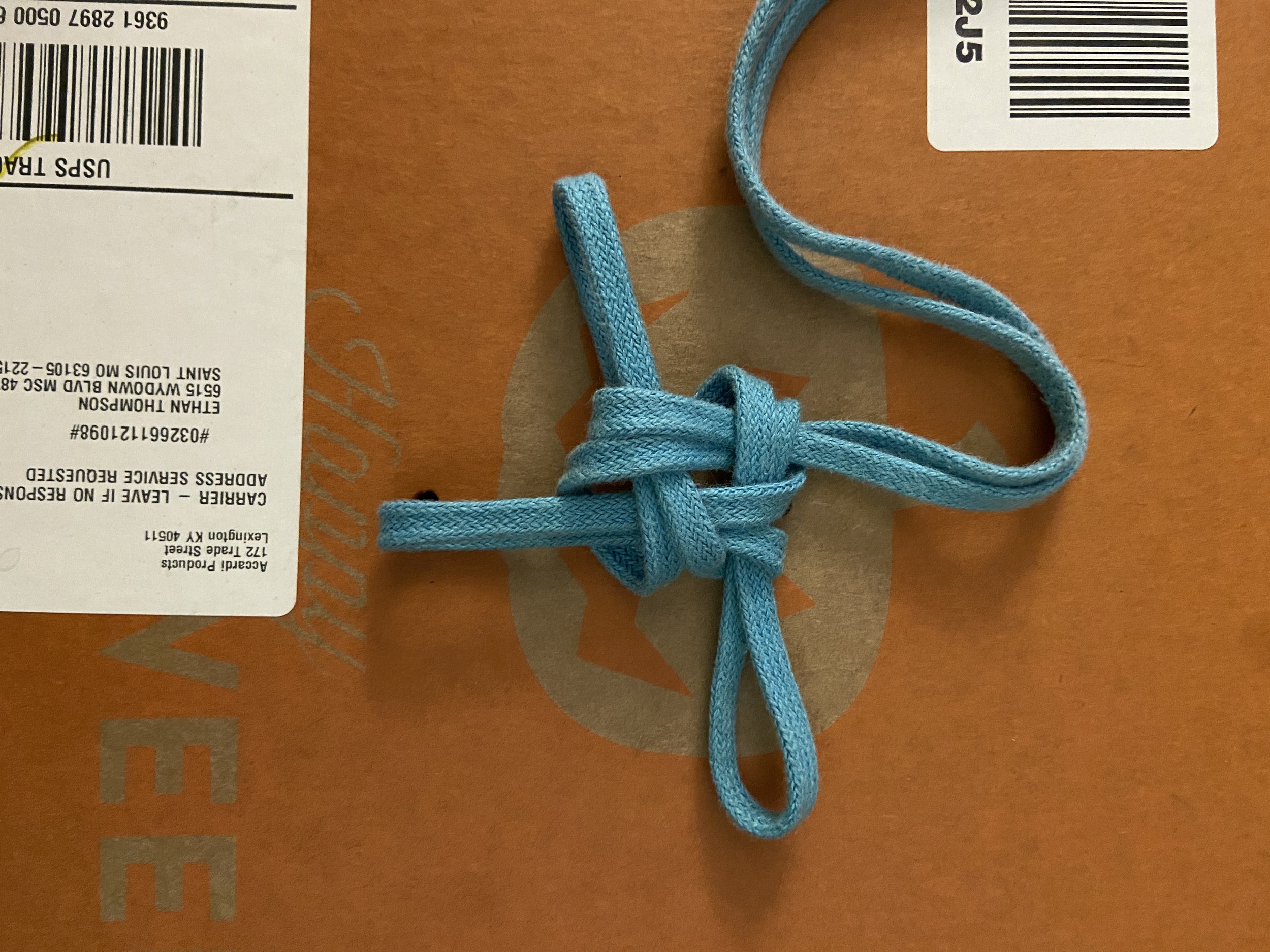

The central theme of my experiment is a technique recreation, specifically recreating the knots of Maedeup. To prepare for this, I purchased nylon thread, what I believed to be the closest available approximation of dahoe. I then set out to make as many different kinds of knots as I was able to. I began with the simple dorae (도래) knot which is marble shaped. This knot was relatively simple and I was able to assemble a string of dorae with green and thread. Though the thread began to twist, likely due to my inattention to string direction, the Maedeup came out cleanly. I then attempted the dongsimgyeul (동심결) knot which I was unable to complete. The thread that I used was too thin to accommodate the complete twists and turns of the know. However, all was not lost. I tried using a shoelace, which was thick enough to complete the knot. I then moved on to sul, the tassels. I created a ttalgi (딸기) tassel, also known as a strawberry tassel. This tassel can be created without a frame which is the approach I chose to go with due to earlier failures in attempting to create a functional tassel frame.

Conclusion:

In a later experiment, I would definitely buy a thicker thread or even attempt to seek out actual dahoe. My attempt to replace it with nylon thread was misguided. It assumed that any woven thread would be functional when a certain thickness was necessary. Dongdahoe would be the type of dahoe used to make the Maedeup I was attempting and that requires at least a sixteen-thread dahoe (Kim 2016, 145). I would also consult more craft-building sources, as I did not anticipate the difficulties of interpreting written instructions and unclear pictures when working with something like knotting, a practice that leans heavily on tacit knowledge. Kim discusses how the knot-creating methods were “passed down by word of mouth by artisan to artisan” (Kim 2016, 155). It was almost prideful to presume myself as part of this lineage of tacit knowledge, and for that pride, I fell.

On that same note, I believe my analysis reinforces Guth’s belief from the excerpt Tacit Knowledge. Guth posits that tacit knowledge is the most important tool for learning craft, that the “flow of activity that constitutes craft-making does not lend itself easily to words” (Guth 2021, 140). I was provided with written instruction from a Master of the craft, one of the most knowledgeable people when it comes to Maedeup. However, I was still unable to perform a fully accurate recreation because I lacked the unspoken, tacit knowledge. One might argue that this spells out the end for many craft forms as if someone can not learn from the master’s compendium of knowledge the craft must be unsavable. Contrary to that, I think this knowledge gap just means that more craft scholars and apprentices are necessary. They will study under these masters and preserve the craft.

Works Cited:

Guth, Christine. “Tacit Knowledge.” Chapter. In Craft Culture in Early Modern Japan: Materials, Makers, and Mastery, 139–64. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2021.

KIM, HEE-JIN. Maedeup: The Art of Traditional Korean Knots. WEATHERHILL, 2016.

“Maedeupjang, the Craftwork Which Completes ... - Youtube.com.” YouTube. 문화유산채널[K-HERITAGE.TV], October 5, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hhO6hvz_4Zo.

Park, Yoonmee, and Choi, Yeonwoo. “A Study on the Distribution and Tools of Dahoejangs in the Joseon Dynasty.” The Research Journal of Costume Culture. The Costume Culture Association, October 31, 2014. http://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/JAKO201431763841462.page.