Okuma Shigenobu’s Western Kitchen and Kuidoraku

Introduction

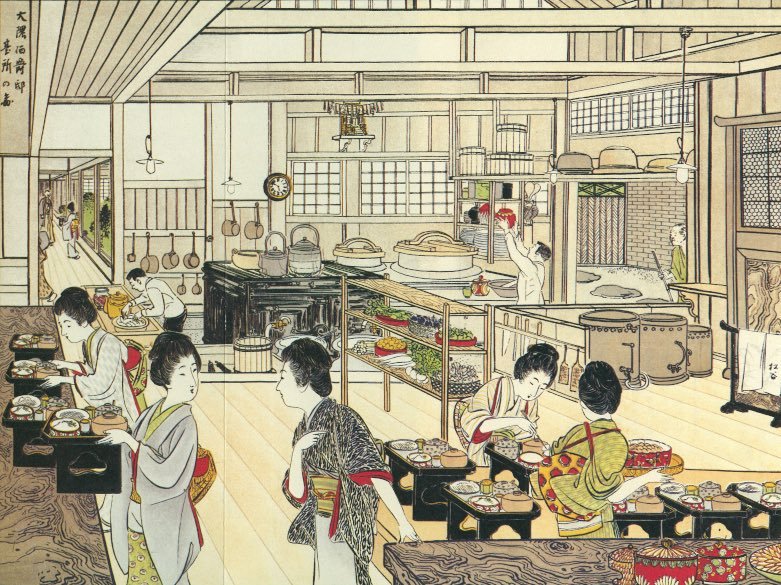

As Western influences started to come into the daily lives of people in Japan through its shift during the Edo period to the Meiji period, there was a shift in approach to food production and there was a peak in interest in investigating and writing about it. 食道楽 - “Kuidoraku” published in 1903 was one of the most popular works of writing by Gensai Murai, illustrating a story of a girl Otowa and her experiences with foods during the changing four seasons, revealing yoshoku and washoku food elements. In ”Kuidoraku - Spring Edition”, Murai studies former Prime Minister Okuma Shigenobu’s kitchen at Waseda University, which he founded. Brought in as an example to show Western influences coming into the kitchen of the upper class, studying the image and the text reveals the benefits of Western technology in the kitchen, as well as the social and cultural shifts evident through how the cooks and workers are being portrayed. Through physically modeling the space from the image, this project seeks to understand the ratio of Western and Japanese in this space, and what Japanese technologies were implemented during a time that was in the midst of change. A transition of cooking on the floor sitting, using the irori has now shifted to cooking standing up - which started in the upper class but through idolization and convenience of this lifestyle, slowly made its way to the common household. A study of the scale of the kitchen and of the heights of elements in the kitchen reveals this shift in behavior.

Edo to Taisho – A Shift in Culture

There was a concept of the doma, meaning “dirt place”, where instead of tatami or flooring, there is an area in the house with packed earth. In houses like this, the doma was considered the kitchen, therefore making the place of cooking and eating in the same space. The smell of the smoke and fire would be spread throughout the house – concepts introduced through the uses of the irori. The irori was useful in that one could dehydrate foods and be provided of warmth simultaneously, while creating a space of gathering. From the Heian period to the Edo period, the concept of the kitchen “daidokoro” was introduced, where plating the foods, and the wealthy were introduced to the concept of dividing the eating and cooking area. The shift from Meiji period to Taisho shows the direct shift to cooking standing up – the model and image shows workspaces being created near the stoves, where the assembling is confined to the back of the kitchen, creating a separation between the tasks. The Taisho period also saw the introduction to eating together as a family by sitting around a table – a relatively Western concept at that time.

Figure 2 - Interior of 完之荘, showing irori

Figure 3 - Traditional Kitchen Space - doma

Significance of the Kitchen

While this kitchen was well equipped with the highest technological advancements and Western influences, it was later revealed through research that the chefs were relatively unhappy with the experience in the kitchen. In “Chawa”’s “The Chef’s Cries”, it was shown that the chefs were unsatisfied that despite the excellent facilities, they were unable to utilize it in the best of their abilities given that Okuma favored soft food, and as long as things were shoppai, or salty in taste, it was dismissed as passable – therefore experimentation wasn’t encouraged as much as it could have been.

Still, this kitchen introduced many concepts of firsts – Shigenobu had lobbied for Tokyo Gas Company to connect a gas line to the kitchen in order to use the newly imported gas stove from England. While the kamado was something made in Japan, it was a gas kamado, allowing ease in controlling heat. The stove was also utilized for controlling heat - Western cooking requires high heat, and this allowed flexibility in cooking efficiently and at a faster pace. The fire was produced by gas, which was very rare considering gas was primarily used then for lighting only. The shichirin had proven its limitations, as harder to control and time consuming. When gas-fired stovetops reached the mass consumer market in 1904, schools had slowly began to introduce Western cuisine and Western style cooking into their curriculum to react to this shift.

Inside the kitchen, one can see Western clothes being introduced for the male chefs, while the female are still seen to be wearing kimonos with tasukigake, the practice of tying up the kimono sleeves to prevent them from getting dirty. While Western dressing for women were introduced after the war, we still see here that women, and people eating in the background hallway are seen to be wearing the kimono, while the men are seen to be wearing Western style clothing.

-

石炭や薪炭のかわりに何でもガスを使う仕組みですから、煙が出て燻る憂いはなし、石炭や薪を運ぶ手数もなし、鍋の裏に煤がついて洗うという世話もなし、急いで火を起こすという世話もなし、火が要るときは一つネジをひねるばかりで、強くも弱くも自在な火ができて、何時間でも平均した熱度を与えられますから、ガス竃になって以来、一度も飯の出来損じがないそうです。それで時間も早くできます。一升の飯が十三分、二升が十五分、三升が十八分と、時間が一定していて、じわじわ時に蓋取るなと叱られる世話もありません。ストーブの方もその通り、西洋料理でも日本料理でも、火力が一定しているから一度火加減さえ覚えれば早くできて失敗がありません。それお客だ大急ぎでお料理をこしらえろというようなときに、ガスストーブだとどんなに楽かしれないそうです。それで費用はどうかというのに、以前、石炭や薪の時代に台所だけで一日一円五十一銭掛かったのが、ガスになって九十五銭で済む。費用も少なく清潔で便利で人の手間もよほど省けます。

-

With the introduction of gas, there is no need to worry about smoke coming up or carrying coal or wood, the cleaning of pots, or having to put the fire on in a rush. When in need to start a fire, one simply must need to rotate a screw and can sustain the temperature for a number of hours – since the introduction of the gas kamado, there are rarely instances where food is spoiled or ruined. Time is no longer a concern for worry, were one cup of rice can be cooked in 13 minutes, two in 15, three in 18minutes, where the time is predictable and one doesn’t need to be manning the kama at all times. Utilizing the stove is easily translated into Japanese cooking through Western concepts; after getting used to controlling the fire, it is almost certain you won’t ruin the dish. When in a rush to serve food to customers, the gas stove makes it fun. In terms of cost, while coal and wood would cost the kitchen around one yen 50 sen, gas only costs 95 sen – proving a chepaer, hygienic, and easy to use method for people to utilize.

Figure 4 - Asahi Newspaper January 15th, 1922

Figure 5 - Asahi Newspaper January 9th, 1922

A Closer Look at the Image – Using the Model

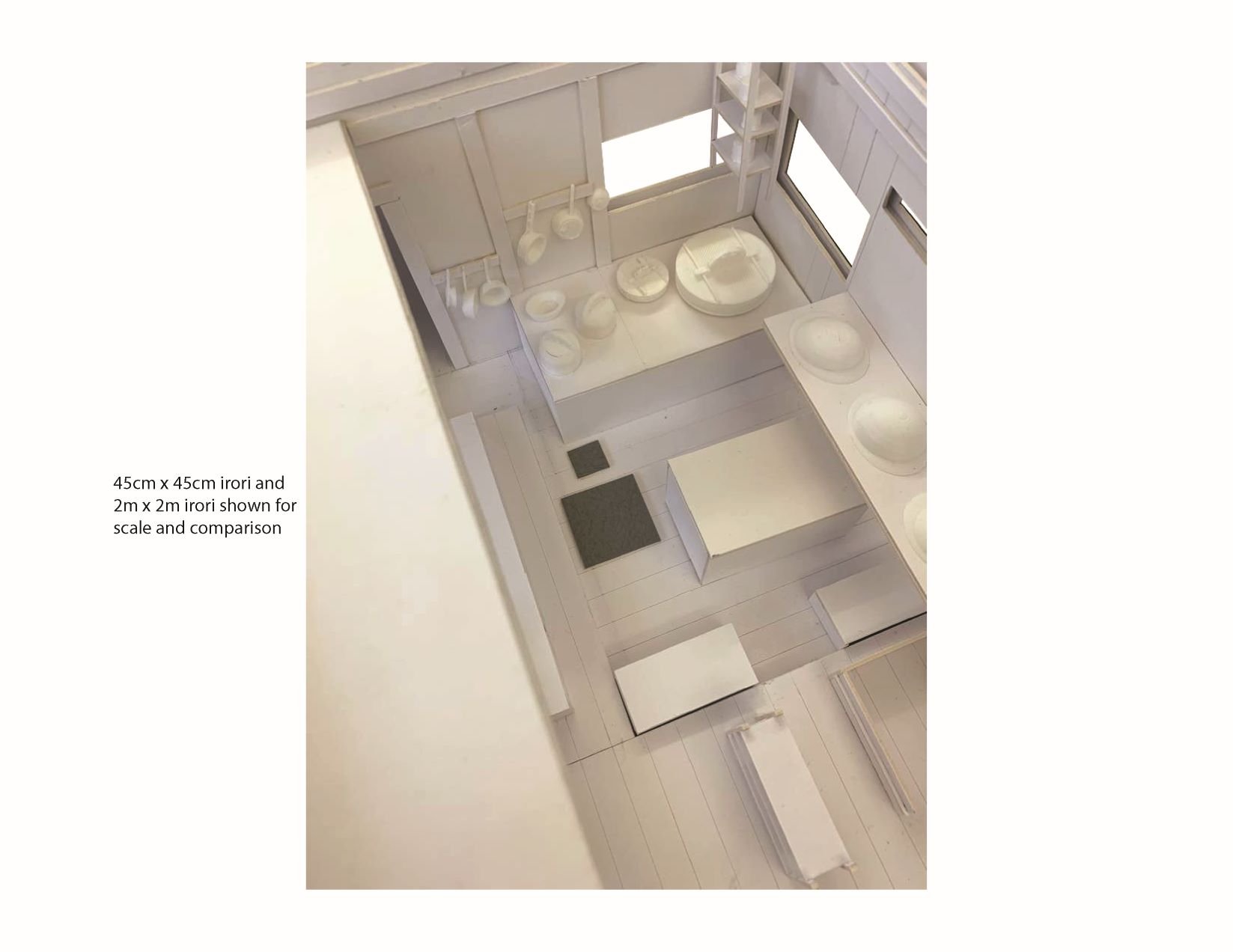

“Kuidoraku” explains the dimensions of the kitchen in detail – while the cooking area is seen to be 5 tsubo, the wooden area to be 25 tsubo, a total of 25 tsubo or 50 tatami sheets can be anticipated for the kitchen. Although in construction it utilizes traditional Japanese techniques, the introduction of the Western gas-stove shifted the organization of the kitchen into three parts – the cooking, assembling, and carrying. In the image, they are cooking traditional Japanese cuisine of nimono, sashimi, and fried foods – anticipated to feed around 50 people a day. The vegetable storage cart in the middle of the kitchen was seen to be equipped with vegetable that was able to be preserved at room temperature – as it would take a few more years for the refrigerator to be introduced into the Japanese kitchen. The tools used for cooking doesn’t seem to have shifted, where you can see a slicer, knives, shamoji, and traditional red pots in the right corner that symbolize a condiment section of the kitchen including salt pots and miso pots. The kitchen also introduces a clock – a Western invention, but also symbolizes the concept of time introduced into the kitchen through Western cooking. One can analyze the shear scale and size of the kitchen through comparing it to the traditional irori - I inserted a sheet to show in reference two irori sizes, the 45cm x 45cm used for traditional teahouses, and the 2m x 2m which were seen to be the maximum size. Comparing can show how the stove has replaced just even in terms of how much space it occupies, but how in elevational a shift in eye level can be seen through the different uses as well.

Figure 6 - Process rendering of 3D model

Figure 7 - Space being populated

Expanding on the Investigation

The model can be pushed further and be used to study not only height and circulation, but test the passage of time. The model’s measurements can be used by a researcher to look at exactly how much time was saved by cooking being shifted to the gas stove. Through creation of several iterations of kitchen spaces both in different households but throughout the Taisha period progresses could be interesting to see in terms of how greater efficiency is placed in food production. The plan of the kitchen of Okuma Shigenobu reveals a lack of efficiency in terms of order of process of producing food - it would make better sense for the cooking to be in the back and then the plating, lastly a clear pathway to move in to the hallway to distribute. Instead, the plan shows the kitchen portion being closest to the hallway - which could be attributed to a number of reasons. It could be reacting to the concept of the doma and irori, and how close in proximity eating and cooking used to be. The kitchen could be supplying the smell and atmosphere similar to those concepts by being situated near the door. Another reason could be to emphasize the technological advancements as a way for Shigenobu to showcase his strength and wealth. As an educator and public figure, he may have wanted to show his progressive and welcoming character by incorporating and pushing for Western influences to be implemented.

The current plan breaks the clear circulation by the chef cooking and plating directly infront of the entrance into the kitchen space, putting the area of plating and carrying to the back of the space when in reality that would be the most congested/dense/populated area. Even in the image it is made prominent the shear density of the space just by the number and size of the figures in that space compared to the rest of the kitchen area. Expanding this and researching more on what lead to this shift in circulation in conjunction with the normalization of separation of eating and cooking could be interesting.

“朝日新聞記事検索サービス.” n.d. Database.asahi.com. Accessed December 7, 2021. http://database.asahi.com/library2e/main/top.php.

村井弦斎. n.d. “食道楽.” Www.aozora.gr.jp. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www.aozora.gr.jp/cards/000810/files/49947_40166.html.

“大隈重信伯爵家の台所.” 2017. 閑人のお遊び. March 17, 2017. http://kanzinn-no-oasobi.net/okuma-sigenobu-murai-gensai.

“第5話 大隈重信のプロフィール - 明治の総理大臣たち(井上みなと) - カクヨム.” n.d. カクヨム - 「書ける、読める、伝えられる」新しいWeb小説サイト. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://kakuyomu.jp/works/1177354055584294661/episodes/16816410413964141572.

“ほぼ日刊イトイ新聞 - 江戸が知りたい。東京ってなんだ?!.” n.d. Www.1101.com. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www.1101.com/edo/2003-09-24.html.

“料理人が語る大隈の好物 - 早稲田歴史散歩.” n.d. Wasedaa.blog.fc2.com. Accessed December 7, 2021. http://wasedaa.blog.fc2.com/blog-entry-7.html.

2021. Waseda.ac.jp. 2021. https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/i14/i14_d0547/.