Making Tofu: A Staple in East Asia

What is Tofu?

Tofu is made from coagulating soy milk and can come in a myriad of textures, from silken to extra firm. It has a subtle flavor, making it a popular and versatile ingredient in dishes across east Asia. Tofu, an ingredient I recognize fill the aisles of the Asian grocery stores I go to, is oddly unfamiliar when I think about how it’s made. This disconnect between a food I regularly eat and its making process compelled me to recreate tofu in hopes to fill this gap.

There are several existing theories about the origin of tofu in China. One explains how tofu may have been accidentally discovered by noticing coagulation from a soybean soup that had been seasoned with unrefined sea salt. Another theory states how making tofu may have been based on the cheese-making process of Mongolian tribes in northern China. [1] While tofu originated in China, it has spread to other areas and has become an integral part of the food culture in other countries. In the mid-Joseon period, Korea was a massive producer of beans, including soybeans specifically. Soybeans were used to make many soybean-processed foods like soy sauce, soybean paste, and tofu. When looking at the records of tofu making, tofu was produced all year round and was primarily eaten in its plain form, grilled, or in a soup. Tofu was primarily made in temples, and people came together to socialize while making and eating tofu. [2] Considering the length to which tofu has lasted as a food product since it was brought to Korea, I wanted to recreate an ingredient that has had a deep history in developing the Korean food culture that is known today. I chose to recreate the tofu that was made during the Joseon period by referring to the recipe in Yu Kim’s book Suun Chappang (수운 잡방). This book, which dates back to the 16th century, has a miscellaneous list of family recipes that gives more insight into how some of these traditional Korean foods and drinks were made at the time. [4]

Recipe

Grind 1 mal of soybeans with a millstone to remove the hulls, and 1 doe of mung beans separately to remove the hulls. After soaking in water, grind it slowly and finely, put it in a fine sackcloth, and filter it finely so that there are no residues. Filter it again, pour it into the pot, boil, and when bubbles overflow, pour clean cold water little by little over the edge of the pot. In general, when it boils three times by pouring cold water three times, it is ripe.

When the beans are ripe, wet the thick seomgeorjeok(섬거적) with water and cover the fire to block the fire. Mix the salted water and cold water thoroughly and pour it in slowly. If you are in a hurry, the tofu is not good because it hardens, so pour it in slowly. When the tofu is congealed, wrap it in a line cloth and press evenly over it. [3] (Translated in English)

Ingredients/Anticipated Challenges

The ingredients list required for making tofu is short: soybeans, mung beans, salt, and water. I found the challenges came with specific measurements and the making process. The recipe mentions measurements for the beans in terms such as mal(말) and doe(되) which were unfamiliar to me. These are actually traditional units of measurements used in Korea, where 1 mal is roughly equal to 10 doe. The large ratio would mean I would end up using a minimal amount of mung beans for the recipe, and so I decided to omit it during my trials. Considering the similarities of mung beans and soybeans, especially in the use for this recipe, I decided to just replace the mung beans with solely soybeans. For the making process, the recipe doesn’t provide the length of time for any of the steps, and so that is something I had to experiment with as I was recreating the tofu myself.

Trial #1:

Soaking the soybeans

Before grinding up the soybeans, I had to soak them first, so I poured some into a container and submerged the beans in water. Having no experience making tofu, I was left unsure as to how long the beans should soak for. I ended up periodically checking up every few hours, and added more water if the beans had soaked up the water I had poured previously. After about 7 hours, once the beans were fairly soft and expanded, I figured they were ready to grind.

Grinding/Making the Soymilk

In Suun Chappang, there is a picture of the grinder that was traditionally used, which appears to be made of some type of stone. [3]

The millstone that was traditionally used to grind up the soybeans. [3]

Not having this specific grinder, I was unsure as to how I would granulate the soybeans. Initially, I attempted to mash the soybeans in a bowl, but the beans were too firm to break down finely. Looking at what else I had in my kitchen, I transitioned to using a blender. The recipe mentions filtering the soybeans until the resulting product had no residue, and so I added about equal parts water to 2 cups of soybeans until the mixture became a liquid. Given the lack of measurements, the initial mixture was too thick, so it wouldn’t filter through the sackcloth. I added more water into the blender, which turned out to be more successful. I used the sackcloth I had to filter the liquid twice, as the recipe mentioned, and the result was a fairly smooth soy milk.

Heating/Coagulating

I then transferred the soy milk into a large pot where I would boil it. The recipe mentions pouring cold water to the edge of the pot three times, which was hard to interpret. [3] I didn’t know if those making this recipe during the Joseon period poured the cold water into the mixture or onto the pot itself. Since it isn’t feasible for me to pour the water onto the pot in my kitchen, I ended up pouring the water into the pot directly. Another part of the recipe that may have been specific to the Joseon period is using the seomgeorjeok to cover and block the fire. This appears to have been how Korean cooks lowered the intensity of the heat, but since I am not using a fire, I just lowered the heat on my stove.

To make tofu, a coagulant such as salt water or lime water is needed to break down the water soluble soybean proteins. [1] The recipe mentions pouring salt water into the pot to coagulate the soy milk. I ended up using plain salt I had in my kitchen, but after I poured that in, the soy milk wasn’t coagulating. When looking up the coagulants used for making tofu today, I found that there were specific salts, like nigari, that are used. Nigari is a type of salt that is made from evaporating sea water. Considering Korea and China’s proximity to bodies of seawater, it makes sense that sea salt is commonly used. Because of the lack of tacit knowledge I have in making tofu, it didn’t strike me that certain types of salt wouldn’t work in the coagulation process.

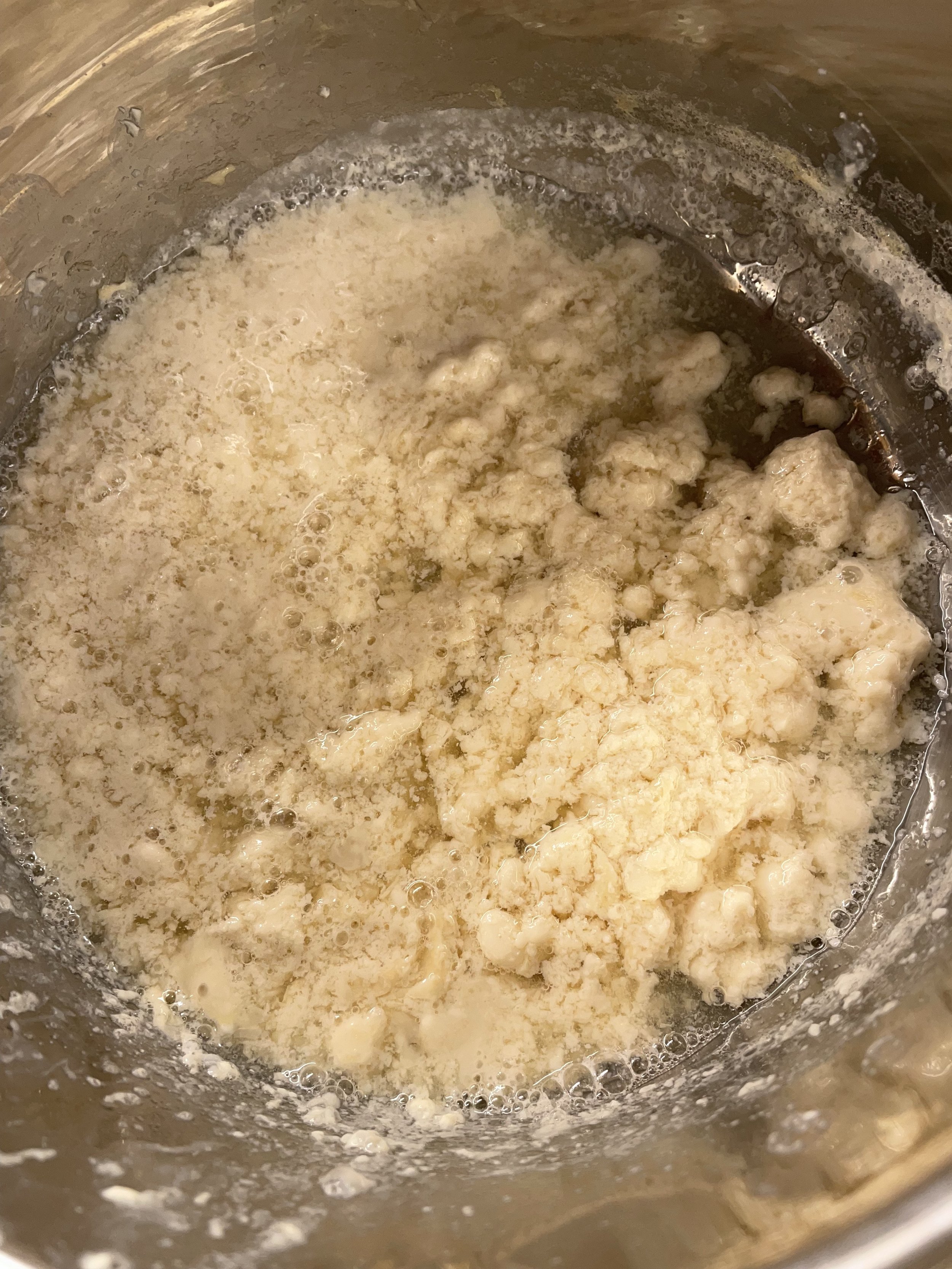

As I didn’t possess nigari, I used another type of coagulant: acid. Similar to lime water, I did have white vinegar in my kitchen, so I poured that into the soy milk instead. After about 10 minutes, the resulting tofu could be visibly seen separating from the water.

Molding the Tofu

I put the solidified tofu chunks into the sackcloth and folded it to create a rectangular mold. Using the container, I pressed it evenly over the tofu as the recipe mentioned. [3] In the end, the consistency and appearance of the tofu didn’t quite resemble that of the store bought tofu I am familiar with. It was crumbly and dry, and it didn’t hold up on its own when picked up.

Reflection

Reflecting on my first attempt at making tofu, there were some key areas I discerned that could have affected the outcome: the coagulant and mold. Not having an actual mold besides the sack cloth could have prevented the tofu chunks from constructing into a firm block. Pressing the tofu too thoroughly also squeezed out much of the water content of the tofu, which is why the consistency was too dry.

Trial #2:

I set out to recreate tofu for a second trial, this time using nigari and a tofu mold. I repeated most of the steps in the first trial, but I added nigari instead of vinegar and used the tofu mold to press down and mold the tofu for about 30 minutes.

Here is how tofu is made today in Gwangmyeong market in South Korea. [5] I referred to parts of the process shown in this video for my second trial.

Conclusion

Looking back at my two trials, the difference in outcomes can be attributed to various factors. A big contributor to my success in the second trial has to be due to the tacit knowledge I accumulated while undergoing my first trial. Seeing what measurements and kinds of ingredients were needed and how to mold the tofu were things that were unclear in the recipe. Recreating the tofu myself allowed me to understand these hidden nuances. Yu Kim, the author of the recipe I recreated, was a male writer at the time Suun chappang was written. Compared to his female counterparts in cookbook writing, Kim had less first hand experience in the making of much of the dishes he wrote about. [4] In turn, a lot of the details that may have been in the recipes written by female writers may have been absent in Kim’s. This may have been another factor that affected the result of my first trial, and reading some of the nuances of tofu making beforehand could have helped it turn out better.

Overall, I would say my attempt at making tofu was a success. The feeling of the firmness of the tofu and its rectangular shape resembles the tofu in the white plastic packaging I am used to cooking with. The tofu I made did have a stronger bean flavor compared to the more subtle flavor in packaged tofu, which can be attributed to its freshness. One thing I would like to try if I could remake tofu is to use the traditional stone grinder. Although I was able to still make the tofu with the tools I had in my kitchen, I wonder if the experience or outcome would have been any different. Furthermore, making tofu also taught me about coagulation as a food-making technique. It would be interesting to see how I could use the knowledge I acquired to recreate other foods that require coagulation. Although I am definitely not an experienced tofu maker, the hands on experience of making tofu for the first time has definitely allowed me to cultivate a greater understanding on what is needed in the making process of not only tofu but crafts as a whole.

Works Cited:

[1] Kim, Bok-rae. “An Anthropology of Historic Foods in Japan, China and Korea.” Journal of Food Science and Engineering, 2018, pp. 112-120.

[2] Kim, Mi-Hye. “Study on the Consumption Status of Beans and the Soybean Food Culture in the Mid-Joseon Period According to Shamirok.” Journal of the Korean Society of Food Culture, vol. 34, no. 3, 2019, pp. 241-254.

[3] Kim, Yu. 수운 잡방. Translated by Ch'ae-sik Kim, 글항아리, 2015.

[4] Ro, Sang-ho. “Cookbooks and Female Writers in Late Chosŏn Korea.” Seoul Journal of Korean Studies, vol. 29, no. 1, 2016, pp. 133-157.

[5] “30 years experience, Korean tofu making process - Korean Food.” YouTube, uploaded by Delight, 8 Feb. 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EfF8b6YaQUM&t=276s&ab_channel=Delight.